His giant achievements are a credit to him. They are also in a way a credit to the US itself.

His family fled anti-Semitic persecution in Nazi Germany in 1938 to come to America. He went back to Germany as a private in the US army and rose to the dizzy rank of sergeant. But then, like so many American ex-servicemen after World War II, he had the chance to go to university and ended up conquering the world.

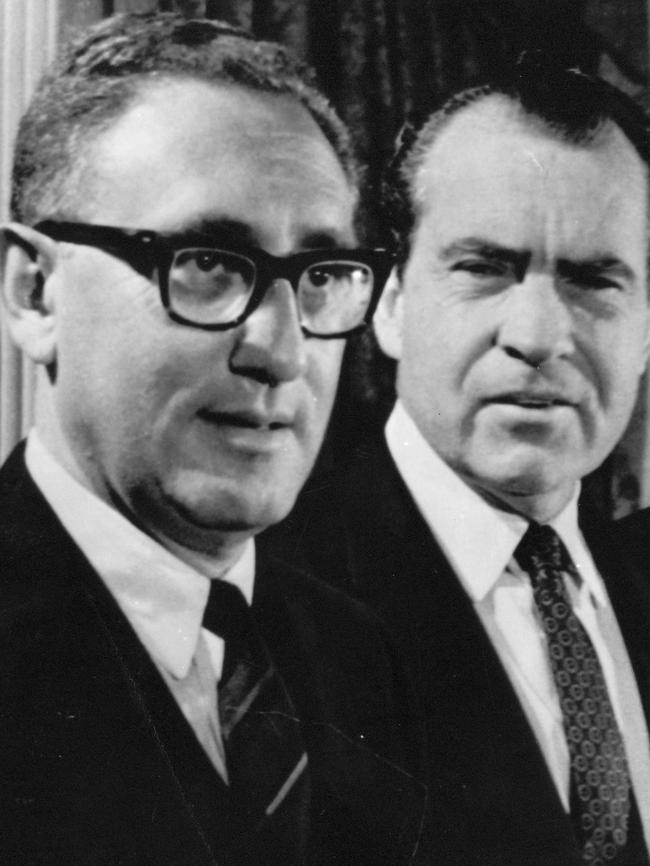

He was national security adviser, then secretary of state, for Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Even by the standards of American politics, and this is no real criticism, he was an extreme kind of egomaniac, although self-aware and often drolly humorous about this aspect of his personality.

He so dominated US foreign policy that for a couple of years he was simultaneously secretary of state and national security adviser, centralising all power in himself and his office.

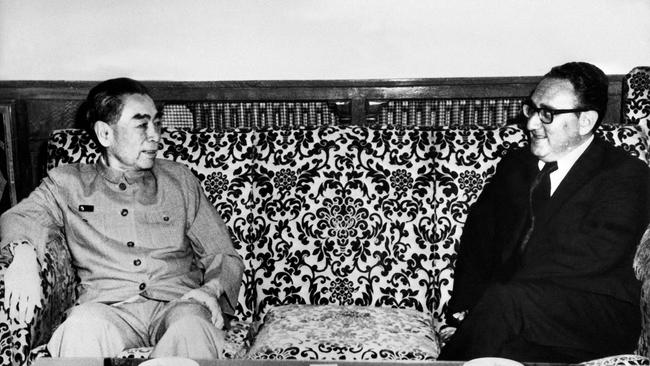

His biggest play under Nixon was the historic opening to China. At almost exactly the time in 1971 that Gough Whitlam as opposition leader was visiting China in public, Kissinger was there in secret, to prepare the way for a visit by Nixon as president.

Kissinger was the first senior American official to visit communist China. His visit, and Whitlam’s, partly grew out of a similar impulse – the recognition that you needed to deal with China.

In motivation and execution, they could hardly have been more different.

Whitlam absurdly romanticised China and sacrificed key Australian national interests to this romanticised vision, especially in our relations with Taiwan and credibility in Southeast Asia.

Kissinger’s effort, though more historic, was much more cold-blooded and involved no romanticism at all.

Kissinger wanted to play China off against the Soviet Union. He saw potential strategic benefit to the US, and to the West generally, in exploiting the Sino-Soviet split.

In Kissinger’s own words, the opening to China gave both Beijing and Moscow an incentive for pursuing better relations with the US.

This was really a brilliant and deft strategic manoeuvre by Washington.

Beijing stopped supporting most communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia. The Soviet Union was deeply nonplussed.

This allowed Nixon and Kissinger to pursue detente with the Soviet Union itself, and to produce two historic nuclear arms control treaties between Washington and Moscow.

This was all in pursuit of the quality Kissinger valued above all others in international affairs, namely stability.

John Howard argues that Kissinger’s strategic vision in pursuing the opening to China more than anything else has defined the strategic environment in which Australia operates.

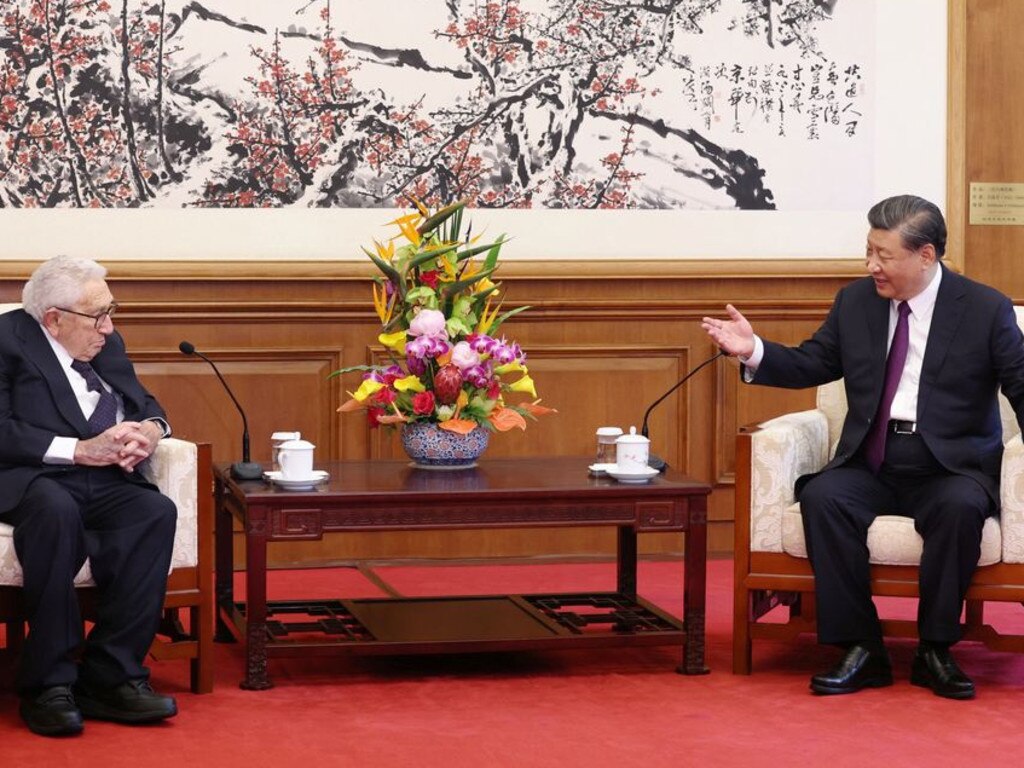

For several decades, the US China policy was an unalloyed success. Kissinger certainly can’t be blamed for the fact that China ultimately became a behemoth, and exploited rather than upheld the international liberal trade regime that Washington invited it to join.

Nonetheless, Kissinger can be faulted for being too soft on China in his influential analysis after he left office. Kissinger essentially defended the Chinese massacre at Tiananmen Square – not the massacre itself, but the Communist Party’s assertion of control.

Kissinger was a classical realist in foreign policy, but this doctrinal realism did not always yield the most realistic or effective policy recommendations.

And although a stabilising influence in Nixon’s chaotic last days, and a mostly steady hand in Ford’s underestimated presidency, Kissinger’s personal style was simultaneously charming and paranoid, generous and manipulative, intellectual and crudely focused around power.

No Republican president after Ford offered him a serious job. Instead, he became the most influential commentator in the world.

Born Jewish and German, he was a true American original and the last great scholar statesman, an independent engine of history.

Henry Kissinger was the most important and consequential American diplomat of the 20th century, and surely the most distinctive.