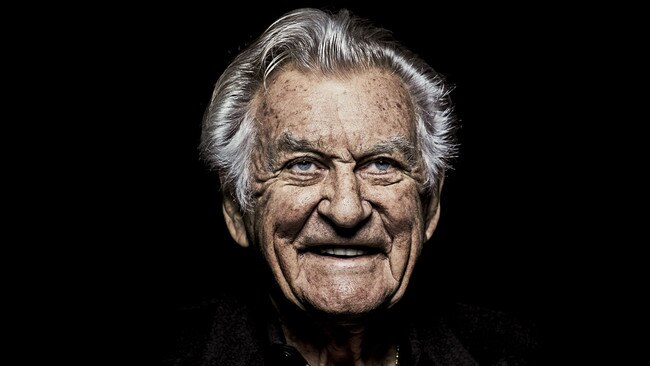

Hawke PM thrived on love of his people

In a final series of exclusive interviews, Bob Hawke revealed he wanted his legacy to be the love he had for the Australian people.

Bob Hawke was the brightest star in the political galaxy. No other prime minister has been more popular; an appeal that transcended generations. No other prime minister could say that their government so fundamentally transformed the economic, social and environmental policy settings of Australia.

He is Labor’s longest serving prime minister, the third longest overall, and he led the party to an unmatched four election victories in a row. And he is the only prime minister to reach a 75 per cent approval rating. Hawke’s rise to the prime ministership was powered by a sense of destiny, unbridled personal ambition and his determination to turn the country in a new direction with consensus leadership supported by a unique bond with Australians.

Hawke embodied a mix of contradictions and contrasts but he was an authentic political leader. While ACTU president (1970-80), he gained a reputation for being a drinker and a womaniser. His emotions, whether revealed by tears or temper, were often in vivid Technicolor display. He never hid who he was or tried to be something that he was not.

He was a larrikin, down-to-earth, sports-loving union leader and prime minister (1983-91) who was also a Rhodes scholar with a commanding intellect. He aroused strong feelings in the 1970s; some Australians loathed him while others saw him as a political messiah. He gave up the booze and moderated his behaviour to become prime minister.

Believing that “ignorance is the enemy of good policy”, he placed a premium on political persuasion, whether by logic, reason or passion. He never treated voters like fools. He was skilfully able to lead a party and a government through periods of profound change at home and abroad while retaining the support of voters.

Hawke’s rise to power took place outside the political system. He was appointed the ACTU’s research officer and advocate in 1958, and within a few years enjoyed a national profile. But it was not until 1980 that he was elected to parliament. Just over two years later he was Labor leader and then prime minister. Although he had been Labor’s federal president (1973-78), he was seen as somewhat above politics.

Earning respect for his ability to resolve protracted industrial disputes in the 70s, Hawke made conciliation the centrepiece of his pitch for the prime ministership in the 80s. He wanted to heal the divisions that defined Malcolm Fraser’s government. In 1983, Hawke promised to “bring Australians together”. He introduced high summitry into Australian politics that provided the basis for landmark reforms. And he emphasised the importance of educating the electorate so they would understand and support the need for change.

The Hawke government was more pragmatic than ideological and many of its policies were crafted by necessity rather than design. But seared into Hawke’s mind was Lee Kuan Yew’s admonition that Australia would be the “poor white trash of Asia” if it did not change its economy and society.

His overarching vision for Australia was to have a more competitive and productive economy and compassionate society at home, and be an independent and respected nation abroad.

As longstanding policy pillars tumbled, and Labor agonised over the slaying of its sacred cows, it was rarely smooth sailing. Cabinet and party disputes were frequent but Hawke managed to keep Labor largely united and steer to victory after victory at the polls.

Hawke changed the Labor Party. Many of its cherished policies were jettisoned, such as public ownership, and a new model was embraced that blended market-based economic reform with a strong social safety net. Labor became a model for social democratic parties around the world.

There were often howls of protest from the left wing of the party, and some unions, but Hawke knew that a new model was needed to reconstruct the economy and reshape society. It was not a hijack of Labor, as some from the academy claimed, but rather a recognition that while the goals of equality and opportunity remained, the tools to achieve them had to change. Leading a Labor government of longevity was one of Hawke’s principal missions and it remains an achievement that has eluded all of his successors.

■ ■ ■

It has been an immense privilege to interview Hawke on more than a dozen occasions during the past 15 years or so, at his home and office, about his life and legacy, and talk with him from time to time on the phone about contemporary politics.

I learned that the key to understanding Hawke’s life is his bond with Australians. His “special relationship” attracted sneers from colleagues and opponents but it was inexorably linked with who Hawke was as a person and political figure. No other politician has come close to emulating this mutual affection, which crosses generations and was the bedrock of his success.

“The Australian people know that I love them and this country,” Hawke told me in a previously unpublished interview. “I just love Australia and I love Australians. One of the strange things for me in politics was to see the way in which so many of my colleagues were actually frightened of the people.

“I genuinely enjoyed moving among Australians, meeting with them, listening to them and sharing their interests. I also had a genuine interest in sport, and played first-grade cricket, so people knew that my love of sport was real. I was also for a long time ACTU president. The Australian people saw me arguing for better wages and conditions. They knew I was on their side. I was for them.”

Hawke’s political ascendancy was, he was told, a matter of destiny. His mother, Ellie, believed he would lead the nation one day while his father, Clem, did nothing to discourage this. He was showered with love and made to believe he was special.

While Hawke did not see the divine hand of God in his remarkable journey from Bordertown in South Australia to the Lodge in Canberra, he did feel that he was being favoured with some kind of “guidance”, he told me. When a motorcycle accident nearly killed him at age 17, he felt his life had been spared for a reason and he was going to make the most of it. This was a turning point.

He joined the Labor Party in 1947 while studying at the University of Western Australia. Albert Hawke, his uncle, later became premier (1953-59) and was particularly influential. Hawke was religious, his father being a Congregational minister, but he lost his faith on a student trip to India in 1952 where he witnessed widespread poverty.

After Oxford, Hawke spent two years at the Australian National University working on a PhD and teaching. He began assisting the ACTU with wage cases and secured a full-time position in 1958. He won a ballot for the ACTU presidency in 1969. He joined Labor’s federal executive in 1971, gained a seat on the International Labour Organisation’s governing body in 1972 and was appointed to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s board in 1973.

No other person in Australian history has been talked about as a future prime minister more than Hawke. The idea was being written about in the 1960s. He was a fixture at the footy and the cricket, and revelled in his celebrity status. Many thought he was a magnetic political leader while some saw him as a polarising figure.

The full gamut of Hawke’s emotions — tears and temper — were so often on display that journalists frequently wrote he had “blown it”. Yet he always recovered and another bout of “when will Hawke go to Canberra” stories would come around.

In 1963, Hawke stood for the Victorian seat of Corio and lost to the Liberals’ Hubert Opperman, a former Olympic cyclist. “That was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Hawke said. While Labor remained in opposition, Hawke’s star continued to rise.

After the 1975 election drubbing, Gough Whitlam urged him to come into the parliament and immediately lead the party. The plan leaked, and although Hawke was lukewarm about the idea, it was in any event killed. “It was a chalice that I was quite happy to see pass by,” Hawke recalled.

Hawke won the Victorian seat of Wills in 1980. But he was reluctant to give up the ACTU presidency, which was then often described as “the second most important job in Australia”. In parliament, Hawke began stalking Bill Hayden’s leadership in earnest. But Hawke’s parliamentary colleagues were not all persuaded that his talents outweighed his flaws, and he lost a leadership challenge in 1982.

“I knew that I had to change,” Hawke told me. He identified with John Curtin, who had overcome his inner demons to lead the nation during wartime. “Curtin was a hero of mine,” Hawke said. “We had in common that we both used to drink too much and gave it up. He brought the country together at a time of war, our greatest challenge.” Hawke had to reform himself before he could reform Australia. Although his ambition burned deep within him and his mother and father encouraged the notion that he was destined for greatness, he had to change. He had to end the womanising and the drinking, and tone down his public displays of anger.

Hawke, like Hayden and Paul Keating, had learned lessons from the Whitlam government, which tried to do too much too soon and was plagued by division and dysfunction. Whitlam, though, was not always helped by Hawke, who often clashed with the government as ACTU leader. Hayden helped restore Labor’s policy credibility, recruited candidates and remade the frontbench.

On the eve of the 1983 election, Hayden was persuaded to make way for Hawke. “It wasn’t as though he’d done a bad job, but the question was very debatable as to whether he could win the election,” Hawke said. “I was fairly certain I could.” Hayden’s resentment lingered but he became foreign minister and had a good relationship with Hawke, and appreciated his later appointment as governor-general.

Hawke fitted into the prime ministership like a hand in a glove. He maintained his larrikin style but was more “presidential” than any other, and the government traded on his sustained high approval ratings for most of the period. Occasional flashes of vanity and arrogance never seemed to do lasting damage. Ministers remember Hawke as a good chair of cabinet. He gave the government overall direction and brought focus, discipline and unity to decision-making. He let ministers do their job while he worked hard to stay across cabinet business. He managed caucus and party conferences well, aided by faction leaders, and insisted on frank advice from staff and public servants.

Hawke was not afraid to retreat pragmatically if a policy became too difficult, which sometimes frustrated colleagues. The government’s poll numbers often seesawed between elections but he always consolidated and never led the party to an election defeat.

Hawke was secure enough in himself that he could share power. The critical partnership was with Keating as treasurer. There was a rivalry between them, which later spectacularly exploded, but there was also a deep affection for one another. The bond between them, which fractured over the leadership and later as they battled for their respective places in history, was repaired in recent years.

■ ■ ■

Hawke told me there were three core areas of achievement for which he most wanted to be remembered. First, he was proud of his 1983 election promise to “bring Australians together” under his leadership with “the three Rs”: reconciliation, recovery, reconstruction. The National Economic Summit provided the springboard for the major economic reforms of the 1980s. “The Australian people responded to that and on the basis of that reconciliation we were able to do what everyone has recognised as the fundamental transformation of the Australian economy,” Hawke said.

The landmark economic reforms included: floating the dollar, deregulating the financial sector, overhauling the tax system with big reductions in personal and company tax rates, slashing tariffs and privatising government assets. The budget was structurally repaired, and spending cut in real terms, which produced four surpluses — the first since the 1950s. These policies laid the basis for three decades of economic growth.

Second, Hawke named changes in school and higher education, which provided greater equality of opportunity.

“It was appalling when I came to office that less than 30 per cent of kids in secondary school stayed on and finished,” Hawke recalled. “This was the lowest in the developed world. I vowed I would change that and moved immediately to establish means-tested education allowances and Year 11 and 12 retention rates went up to 70 per cent or higher.

“It was a fundamental thing to do if you are going to have a decent and fair society. The opportunity for a child to develop his or her talents is not a function of the size of Mum or Dad’s wallet but of their interests and capacities.”

Third, Hawke named his role in ending apartheid in South Africa. Hawke had been one of the leaders for racial equality in South Africa since the 70s. When he became prime minister, he worked with other Commonwealth leaders to tighten the screws with trade and investment sanctions.

“It is the result of an idea I had and implemented, the financial sanctions, that brought apartheid to an end,” Hawke said. “Nelson Mandela said it when he came here. He said: ‘I’m here today because of you.’ And to be able to say we did that is very satisfying.”

He was proud of establishing Medicare and implementing the Accord with unions that moderated wage claims in return for social wage benefits.

His environmental legacy is substantial: stopping the Franklin Dam in Tasmania, setting up Landcare, saving the Daintree Rainforest in Queensland and helping to safeguard Antarctica from mining.

He also forged new relations in the region with the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation multilateral trade forum, and strengthened the US alliance by developing good relations with Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush. Hawke acknowledged that his government misread the economy in the late 80s and apologised for the recession in 1990-91.

His other major regret was not doing more to advance Aboriginal land rights. He blamed Brian Burke, the West Australian Labor premier, who warned of an electoral backlash. “I’m sorry we couldn’t and didn’t do more,” Hawke told me.

■ ■ ■

In recent years, Hawke expressed his disappointment in the union movement. Membership has plummeted to negligible levels. He thought the ACTU was not attracting the “stream of talent” that it had a generation ago. Unions had lost sight of the national interest, he thought. And he was appalled by the militancy of the Construction Forestry Maritime Mining and Energy Union.

Hawke was concerned that the Labor Party was often too beholden to unions and factions. He worried about Labor reverting to an older model of tax-and-spend politics and not understanding the importance of middle-class aspiration or how markets could produce better economic and social outcomes than regulation and intervention. He did not subscribe to class warfare or the politics of envy. But he remained staunchly Labor and wanted to see Bill Shorten lead the party to victory.

Although he was named Father of the Year in 1971, Hawke recognised that Hazel Hawke was both mother and father. She stood by him, even when he continued his philandering before, during and after the prime ministership. The termination of their marriage hurt Hazel deeply. Hawke told me that the happiest years of his life were during his marriage to Blanche d’Alpuget. But he always loved and respected Hazel, and was with her when she died in 2013.

Reflecting on contemporary politics, Hawke despaired that many of Australia’s best and brightest were no longer attracted to parliamentary careers. The impact of social media was a big factor, he argued. He was open to the idea of four-year terms to provide some stability. Hawke also thought the quality of candidates, from both major parties, had declined markedly. He still supported the idea expressed in his 1979 Boyer Lectures that, if constitutionally possible, people from outside politics should be recruited to serve in cabinet.

When Hawke lost a second leadership challenge from Keating in December 1991 and surrendered the prime ministership, he gave a press conference where he said that he wanted to be remembered as a “dinky-di Australian” who “loved his country” and “loves Australians”.

He was the first Labor prime minister to face a leadership challenge and be felled by the caucus. Most voters wanted him to stay but most of his colleagues felt he could not win another election.

Almost three decades later, Hawke told me that the bond he shared with Australians was what sustained him in public life, motivated him to change the country and gave him faith in the essential decency of the people who lived in the greatest country on earth.

“The genuine love and respect I had for the Australian people was warmly reciprocated,” he said. “I think this is the basic point: that with a lot of politicians they look at them and say, ‘They’re just using us but Hawkie really is one of us’.”

Hawke lamented that so many politicians lacked a clear vision and a sense of purpose and were not able to communicate with, or relate to, voters. “It’s not rocket science,” he said, “but so few prime ministers in recent years have been able to do this.”

Hawke’s life and legacy should serve as a reminder to all politicians of how to deliver lasting reform in the national interest. We will never see a political figure like him again.

Troy Bramston is writing a biography of Bob Hawke that will be published by Penguin Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout