Freelancers shed light on Bruce Pascoe’s claims in Dark Emu

The authors of a forensic critique of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu are pulling no punches.

It took seven years for Australia’s anthropologists and archaeologists to test the claims in one of the most popular books ever published about First Nations people – the best-selling Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Agriculture, by Bruce Pascoe.

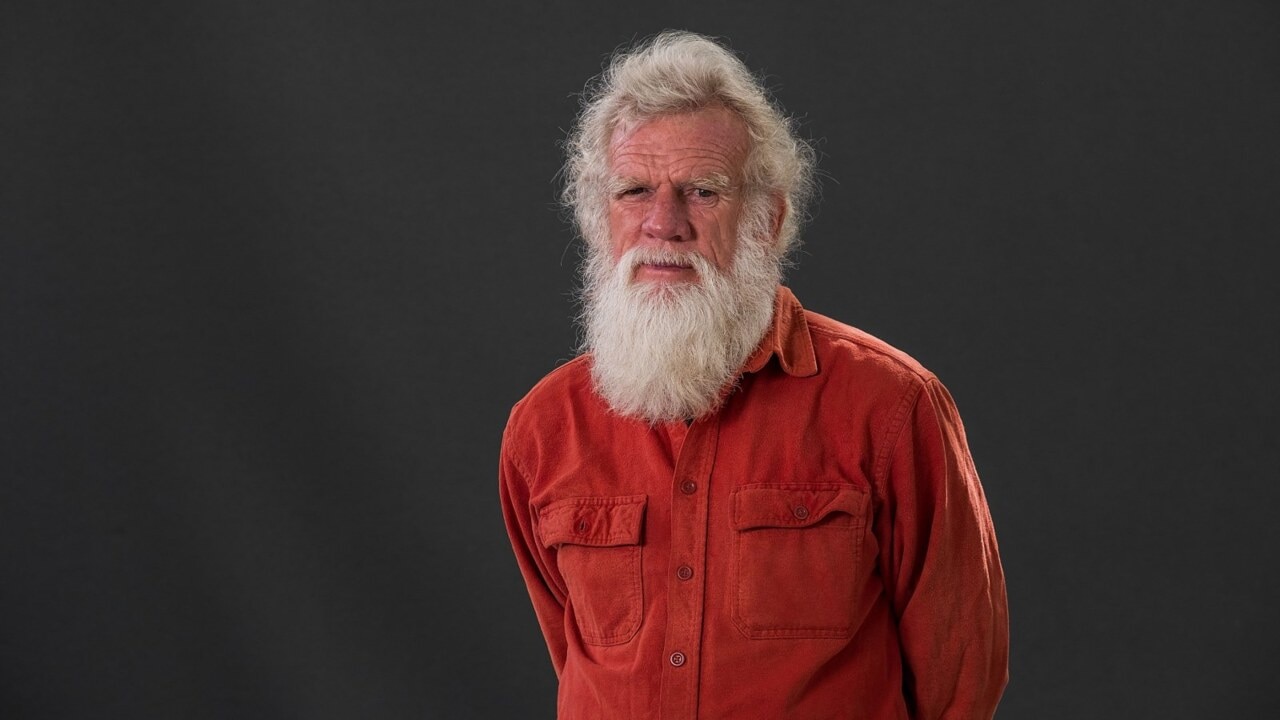

And it’s telling that Peter Sutton and Keryn Walshe, who somewhat reluctantly took on the task of challenging Pascoe’s thesis that pre-colonial Aboriginal people were agriculturalists who built stone houses and cultivated the land, are freelancers who work outside the academy.

Their book, Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate, published last year, has been short-listed for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, in the running for the $80,000 top prize in the history section when winners are announced on December 13.

They were late to the fray, partly because they didn’t take Pascoe’s 2014 book very seriously and were busy with other work, but Sutton thinks the silence from the universities stemmed from fear.

“You can lose a job (if you challenge an Indigenous issue),” Sutton tells Inquirer from his home in South Australia. “You can be vilified in public or in social media. It’s notable that both (of us) are retired. Most people didn’t have the stomach for the fight because you are cancelled if you have a view that’s not liked by certain people, you are cancelled simply on the basis of being white.”

He says if the “relevant scholarly professionals” had reviewed Dark Emu – said to have sold more than 250,000 copies, generated a children’s edition, and on school curriculums – they would not have had much of a future.

Instead, says Sutton: “What happened was that Bruce developed more and more of a public image. In fact, he became someone with instant brand recognition among the middle classes.

“(As) part of the genre of anti-racist literature in this country, (Dark Emu) appealed to people who were concerned about the wellbeing of Indigenous people.

“There were lots of stories of gaps that wouldn’t close and other depressing things about children not attending school. So here’s something that comes along with a positive message. It’s anti-British, anti-colonial.”

Sutton says Pascoe’s identification as Indigenous didn’t hurt either: “No one would have bought a book … written by a white fella from Mallacoota.”

At 76, Sutton is one of the nation’s most significant social anthropologists and linguists who has worked in the bush for more than 50 years – recording and learning Indigenous languages, mapping Aboriginal cultural landscapes, and working on a total of 87 land claims.

He has written or co-written 15 books on Indigenous issues, including his controversial 2009 challenge to public policy, The Politics of Suffering: Indigenous Australia and the End of the Liberal Consensus.

Born to working-class parents in Melbourne in 1946, he went to “the only school for Christian Scientists’ children in Australia”. He became “devoted” to the metaphysics of the religion and as a young adult spent two years as a Christian Science practitioner, or healer, someone others seek out for “assistance and wisdom and things to read and also for healing”.

Later, armed with his degree in literature and linguistics, he did bush fieldwork, recording – and learning – endangered Indigenous languages in Queensland. He is still in touch with the great great grandchildren of the Old People he sat with 50 years ago.

“There are many (descendants) who don’t speak the language but want to know more about the very big movement in Australia and Canada and the US for language revitalisation,” he says.

In 1970, he made an extensive field trip across the eastern Gulf country of Queensland to Palm Island, working there with Indigenous man Johnny Flinders – one of the last speakers of the Wurriima or Flinders Island language. Johnny is dead and Sutton says that he is now the only person alive who can speak the language.

Back in the city, Sutton spent a couple of years in the sound section at the then Institute of Aboriginal Studies in Canberra before heading bush again in 1974 on a long ethnographic mapping trip. It was a “much more muscular activity (than the language trips) involving some fairly strenuous fieldwork” and Sutton loved it.

The next year, he was out again, mapping hundreds of sites across 300km from the Lockhart River settlement south to Port Stewart. He spent three years from 1976 on field work with the Wik people in Cape York, first for a PhD in anthropology then anchoring the anthropology for the Wik native title case. In 1979, he went to work exclusively on land claims for the Northern Land Council before moving with his young family to settle in South Australia.

Since then he has been largely self-employed, working continuously on land claims, publishing widely, and attending professional conferences. He spent six years as head of anthropology at the South Australian Museum and holds an honorary position with the University of Adelaide. He has done casual teaching, but has never had a permanent university job.

You get the sense he could have done without writing the Dark Emu critique but felt it important to refute an author he accuses of “cherry picking” evidence to suit his thesis. He says: “Scholars have extensive libraries and it took me a few seconds each time to go to my library and pick up most of the sources … and check whether they were correctly used.”

Sutton has written most of the forensic examination of Pascoe’s claims but asked Walshe, who worked at Flinders University and the South Australian Museum before leaving to pursue her own research, to add her archaeological expertise to the book.

Walshe had found Dark Emu impossible to read. “I couldn’t actually get through it … I just began seeing so many problems with it,” she says. “But I could see the pace of the narrative was exciting to some readers and it almost had the thrill of an adventure. I could understand people getting captivated by it.

“But in the end, I was confounded because (the excitement around the book) suggested the average reader, even a well-informed one, doesn’t actually have a good grounding in Australian Aboriginal culture. That was really quite alarming. People seem to be so taken with it … seeing it as a truer history, or perhaps the only history they have ever absorbed.”

Walshe anticipated being caught in the culture wars – “that the Andrew Bolts of the world would latch on to it” – but says it’s not been as bad as she thought. She has been disconcerted, however, when meeting Indigenous people who are unhappy with Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers but who confess they haven’t read it. In the main, those who approach her have felt uneasy about Pascoe’s work and are “deeply grateful” for a cautious, science-based critique.

Did the academy, who know so much about pre-colonial Indigenous life, fail to explain this to Australians? Says Walshe: “In Australia we struggle to popularise academic work. There’s a real gap in the publication market. I don’t think it’s the fault of academics because they’re under enormous pressure to keep up their own profiles via research and they don’t have time to write a popular book.”

Sutton is more direct: “There were heroic efforts to penetrate the wider society for the past 60 years. If people say that we weren’t told about this, they are just showing that they are ignorant … Unfortunately, Pascoe was not aware that many of these issues had been gone into.”

Walshe contributed two chapters that include a refutation of Pascoe’s claims that Aboriginal people have been present on the continent well beyond the generally accepted span of more than 60,000 years.

“Some of his claims were pretty wild, getting up to 100,000 to 120,000 years, for which there’s absolutely no evidence at all,” Walshe says.

She also challenges Pascoe’s claims that western Victoria and the area around Lake Condah was a region of complex eel farming where permanent populations built stone houses and preserved food.

Walshe says western Victoria is “a fabulous place, and archaeologically it’s really interesting, there’s no disputing that, but the claims for the processing of eels I have always felt were exaggerated and unfounded. Certainly, people were trapping eels and catching eels. It was a seasonal activity that people flocked to and really enjoyed. It was a chance for high protein and plenty of food. So I could imagine that a lot of people would have gathered at that time of year. But they did not preserve yields, there is no evidence for this whatsoever. They did not smoke eels in trees, and then store them somewhere for the rest of the season so they could be sedentary in that area.”

And the stone houses? She says rocks were used as a base for scaffolding of tree branches and foliage to create a “warm, snug, cozy little hut” but there is no evidence of more significant dwellings. Nor does there need to be: “(The area) deserves the World Heritage nomination and status. We don’t need to exaggerate it, it is already incredibly impressive.”

Pre-colonial Aboriginal people were great conservers, she says.

“People took what they needed for the purposes of not just feeding yourself but for that communal living. To come together as hunter-gatherers was so important, to be able to share food, because in sharing food, of course, you share story, you share culture, and you create cohesive groups, but there wasn’t any excess … there’s no concept of long-term storage.”

Sutton and Walshe reject Dark Emu’s implication that agricultural society is more developed and “better” than that of hunter-gatherers. “I don’t go with the hierarchies,” says Walshe. “I don’t think it’s a linear progression: we don’t start off as hunter-gatherers anywhere in the world and then finally find our way into agriculture. I think that’s a complete fallacy. There is never any need for a group of people who are living a highly successful and sustainable life to suddenly become agriculturalists.

“It’s certainly not racist to say that hunter-gatherers who were living here were among the best, if not the most supreme, hunter-gatherers in the whole world. Most hunter-gatherers on other continents have had to cease undertaking their way of life or compromised and taken on bits of agriculture and so on, but it was here in Australia right up until almost 1800 that they were living as complete complex hunter-gatherers. That’s remarkable.”

For his part, Sutton is scathing about the idea that “people were actually closer to being British farmers” and thus more advanced. Such thinking, he says, “is the road to hell, because it’s going back to social evolutionism. It’s also a bit insulting to kind of (say) who’s the clever boy now, or they’re so clever. That’s demeaning.”

He concedes Dark Emu has reached a whole new audience and encouraged people to think about Indigenous issues. But he says: “The trouble is there is so much misinformation and disinformation in Dark Emu that someone has now created a body of people whose ignorance or blankness has been replaced by a mixture of fact, fantasy and untruth. That’s an awfully big job to get that undone.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout