Fifty years ago I sat in lecture theatres at the University of Western Australia listening to two giants of anthropology – Ronald and Catherine Berndt – as they taught us about the kinship systems of the Aboriginal people with whom they had lived and studied for decades.

It was detailed and at times dry, and Margaret Mead’s work on teenage sex in Samoa seemed more exciting. To my shame, I couldn’t wait until my final year to study the emerging field of sociology and William Whyte’s work on “Organisation Man”.

I thought of the Berndts and those wasted opportunities to know the 60,000 year-old culture of my own country as I read Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers: The Dark Emu Debate, published last year by Melbourne University Press and written by Peter Sutton and Keryn Walshe.

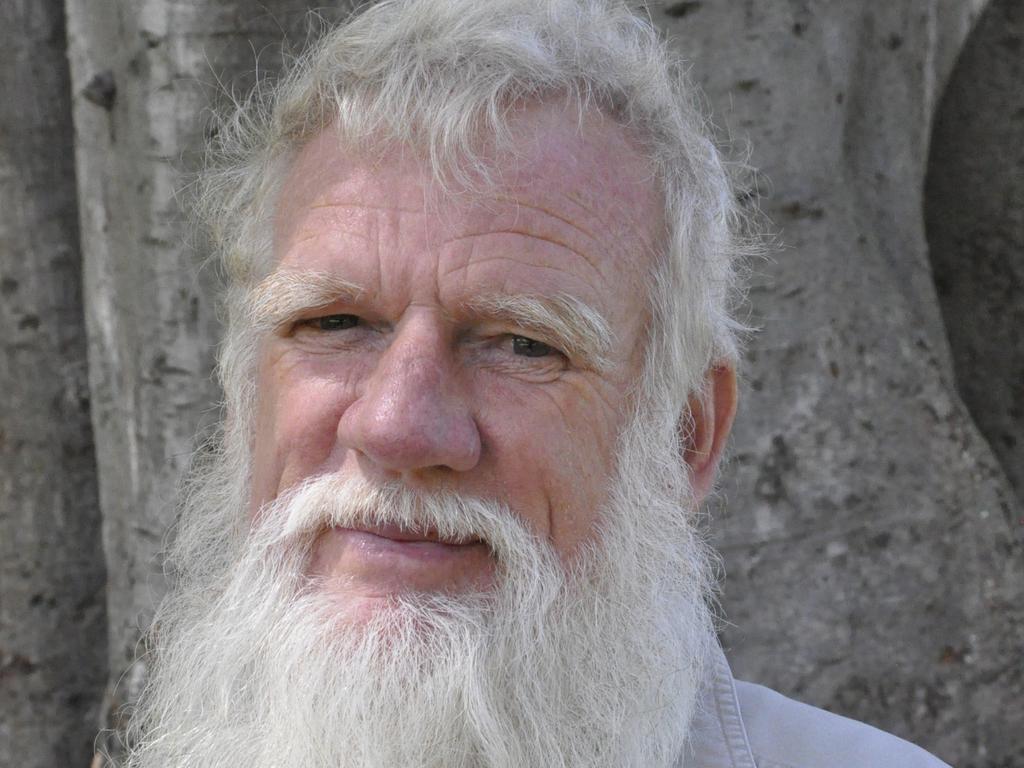

The Berndts are long dead (and out of fashion in some circles these days) but Sutton, who was 30 years their junior, references them several times as key figures in a field to which he too has devoted his life. A social anthropologist and linguist who these days prefers the label of ethnographer, Sutton at 76 stands on the shoulders of the Berndts and others of their era as he challenges Dark Emu, the controversial work by Bruce Pascoe.

Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers (the bulk of which is Sutton’s work) has been seen as a searing rebuttal of Pascoe’s claims that Indigenous Australians pursued agriculture, irrigation and construction before colonisation, that they were not “mere” nomadic hunter-gatherers. The book recently has been added to the Victorian school curriculum to sit alongside the wildly popular Dark Emu. A rebuttal it certainly is but Sutton, who has spent 53 years doing fieldwork in remote communities, is intent on more than an academic critique of the work of man he labels a “myth-maker”.

Sutton appears deeply offended, not just because Pascoe “trims” early written accounts to prove his thesis, or that he offers few caveats, or that he overeggs the evidence, but because in Sutton’s eyes he fails to acknowledge the deep spiritual basis of Aboriginal culture.

He fears Pascoe, in “gilding a lily that needs no gilding, suggests that he sees a foraging way of life as inferior” and thus Dark Emu plays into the colonial-era fiction that First Nations people did not have a real claim on the land, a view that justified terra nullius.

Sutton, who argues First Peoples were “hunter-gatherers-plus”, seems appalled by Pascoe’s focus on the material aspects of their lifestyle, and his privileging of farming societies as more evolved and thus more acceptable to non-Indigenous Australians.

And he is unimpressed by Pascoe’s assertions that his book challenges a widely held stereotype of Aboriginal people as nomadic wanderers. Sutton says scholars repudiated that idea decades ago. Perhaps, but there are many like me, who grew up in an era of assimilation amid a shameful denial of Aboriginal culture, who have not kept up with the vast research in this area. We were told, but we did not always hear.

But equally wrong, says Sutton, is Pascoe’s portrait of agriculturalists who sowed, reaped, returned and repeated.

“Pascoe’s message is built on a simple distinction between what he calls ‘mere’ hunter-gatherers, on the one hand, and farmers,” he writes. “We consider that the evidence, in fact, reveals a positioning of the Aboriginal people of 1788 somewhere between these two extremes and very far from both.” Hence the term “hunter-gatherers-plus”.

Yet Dark Emu has appealed hugely to many Australians who have picked up this accessible – and it has to be said polemical – work and been thrilled by their discovery of the lives of pre-colonial Aborigines.

Sutton, whose book is also pretty polemical, says readers of Dark Emu are “encouraged to feel rushes of wonder for ingenious devices, for ‘achievements’ ”. To him, this is dangerously close to a “Western notion of culture focused on constant innovation, competition, progress and in its lighter moments, gadgetry, gimmickry, smartness, novelty”.

He quotes historian Tom Griffiths: “Pascoe often overreads the sources – and for what purpose? To prove that Aboriginal people were like Europeans? Dark Emu is too much in thrall to a discredited evolutionary view of economic stages …”

Sutton argues the non-adoption of horticulture and agriculture was “not a failure of the imagination but an active championing and protection of their own way of life … they were and are people easily confident in the bush and proud of their ability to run an economy that had a negative impact on their countries … Pascoe’s almost complete concentration on physical interventions in the food supply … downgrades the role of widely practised, complex and highly valued ceremonies and speech acts that constituted spiritual species maintenance.”

It was a subsistence system “embedded in a philosophy free from the ambiguous enchantments of notions of progress”.

It is here that Sutton’s work has been criticised as privileging elements that in turn can be used in the culture wars to diminish First Nations peoples. His views are unwelcome to many keen to address past wrongs through the voice to parliament and who see Dark Emu as an important counter to stereotypes that mark Aboriginal people as the “other”.

The willingness in recent years to recognise Indigenous culture has been crucial in changing public attitudes towards constitutional recognition and the voice referendum. For some, criticism of Pascoe’s work undermines that progress when Australians are being asked to make a leap of faith on the voice.

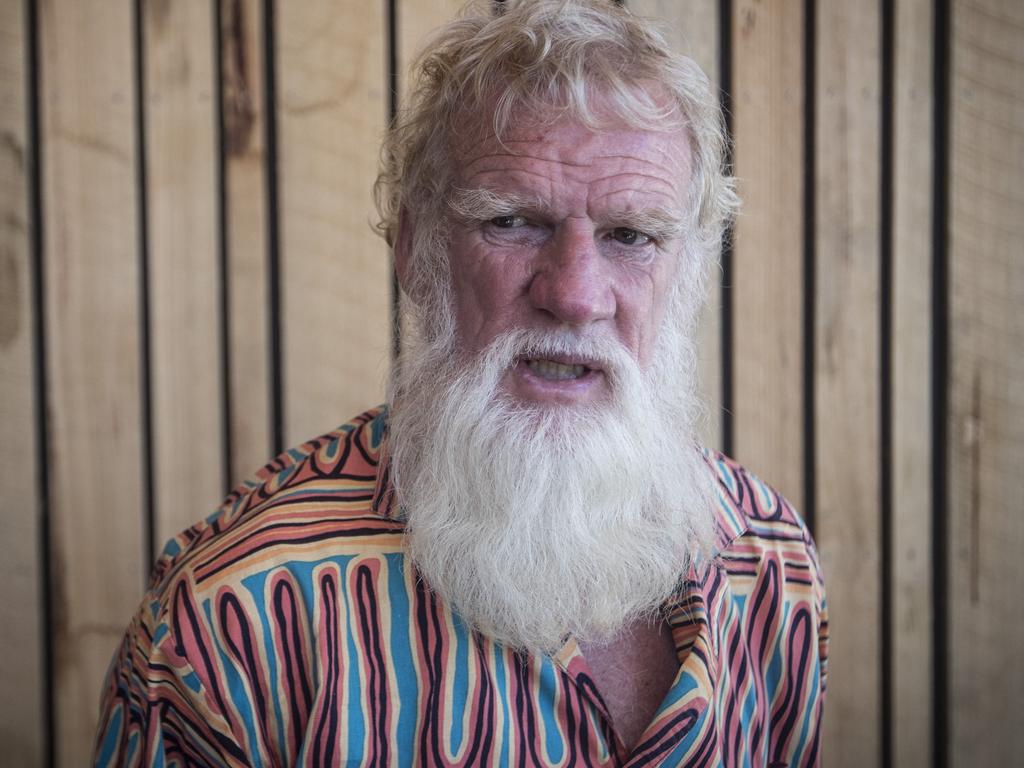

For his part, Pascoe remains untroubled by the Sutton and Walshe book, telling this newspaper recently, “It’s just an opinion, it’s just a book” and saying he had never claimed Aboriginal people were “absolutely” farmers, rather that they engaged in food-gathering practices that were in some cases more like farming than hunter-gathering.

Sutton, it has to be said, acknowledges that Dark Emu has got people thinking and writes: “So long as Dark Emu is not the agent of their entrenchment in a dogmatic view, that is good.”

Above all, he wants us all to develop a deeper understanding of Aboriginal society that recognises the profound spirituality at its centre: to omit this, the book suggests, is to miss the truly extraordinary aspect of our pre-colonial past. Australians, Sutton writes, deserve better than “a history that does not respect or do justice to the societies whose economic and spiritual adjustment to their environment lasted so well and so vigorously until the advent of the colonies and the subsequent degradation of much of that environment.”

They say education is wasted on the young, and certainly some of it was wasted on me.