For health’s sake, keep your distance

Individual actions now have the potential to significantly influence how badly this crisis plays out.

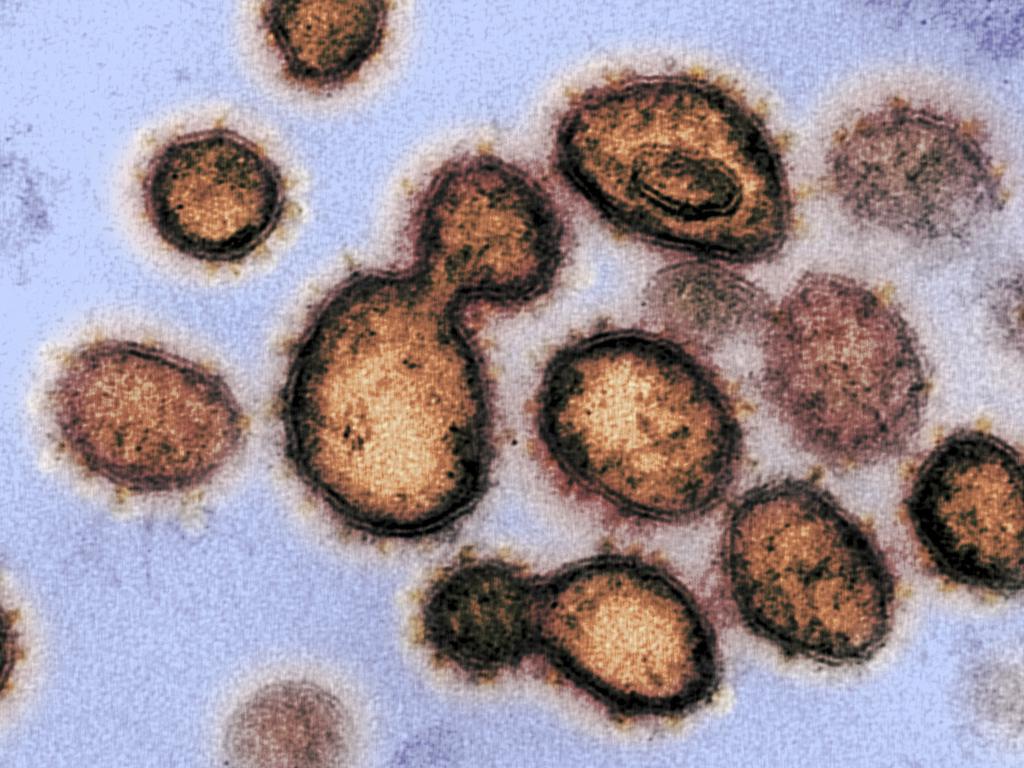

Limited community transmission of coronavirus has begun in northwest Sydney and health authorities are preparing for clusters of transmission around the country. So what lies ahead for Australia, how severely will the coronavirus pandemic hit our health systems, how many people will be infected and how long will the epidemic go on?

There are many unknowns that will impact how easily coronavirus will spread and how many are likely to die. The pandemic won’t be endless, however. It will peak, probably sometime during winter, and then begin to decline. But the actions governments and individuals take now have the potential to significantly influence the size of the peak and the duration of the outbreak.

The aim of authorities is to “flatten the curve” of disease outbreak to allow health systems to prepare and hospitals to cope.

If transmission is steep and wide, intensive care units’ capacity will be overwhelmed and there is the real possibility that doctors will have to make agonising decisions about whose lives to save.

Most experts are optimistic that Australia will be able to keep transmissions of COVID-19 to the low end of projections. But even the best-case scenario is grim: NSW’s Chief Health Officer predicted this week that 1.5 million people, or 20 per cent of the state’s population, will be infected. At a death rate of 1 per cent, that would mean 15,000 dead in NSW alone.

“You will have a peak and then you will have a decay of the epidemic,” says Australian National University professor Shane Thomas.

“It decays either because everyone’s infected and there’s no one left to infect, or you have control measures. So governments and people can in fact alter the risk associated with this.

“Country-based mitigation measures will affect the epidemic.”

A paper published in The Lancet this week canvassed the options available to governments in limiting the spread of the virus. “What has happened in China shows that quarantine, social distancing, and isolation of infected populations can contain the epidemic,” the paper says.

“Singapore and Hong Kong … provide hope and many lessons to other countries. In both places, COVID-19 has been managed well to date, despite early cases, by early government action and through social distancing measures taken by individuals.”

The options available to governments and individuals to slow the spread of COVID-19 are quarantining infected and at-risk people, stopping mass gatherings, the closure of educational institutes or places of work where infection has been identified, and isolation of households, towns or cities.

“School closure … is unlikely to be effective given the apparent low rate of infection among children, although data are scarce,” the Lancet paper says. “Avoiding large gatherings of people will reduce the number of super-spreading events; however, if prolonged contact is required for transmission, this measure might only reduce a small proportion of transmissions.

“Therefore, broader-scale social distancing is likely to be needed, as was put in place in China. This measure prevents transmission from symptomatic and non-symptomatic cases, hence flattening the epidemic and pushing the peak further into the future.

“Broader-scale social distancing provides time for the health services to treat cases and increase capacity, and, in the longer term, for vaccines and treatments to be developed.”

That means that to reduce the spread of disease in Australia, cancelling mass gatherings may not be enough. To really have an impact, governments would have to lock down whole cities or limit the movement of people to within their suburbs, as in China and Italy.

It’s hard to imagine that happening here, Thomas says. “I don’t think we’ll get to that,” he says. “We don’t have a legal or political system that would readily allow for that kind of arrangement. And I don’t think it will become necessary.”

Modelling has predicted a wide range of scenarios in terms of the proportion of people likely to be infected in Australia. The models say that figure could be anywhere between 25 per cent and 70 per cent of the population. The head of the biosecurity program at the University of NSW’s Kirby Institute, Raina MacIntyre, expects the infection rate to be at the lower end of the projections. But even the low end of projections would see about six million Australian infected.

Most — an estimated four in five — will experience a mild respiratory illness and will be able to recover at home. Fever, cough, shortness of breath and muscle aches are common symptoms. The elderly are the most vulnerable, with the death rate climbing to as high as 15 per cent among those aged over 80.

“I think the proportion of the population infected will be a fairly low proportion because of all the measures that we’re taking,” MacIntyre says.

Those measures include rigorous contact tracing and wide travel bans. “I think if we continue with the measures that we’ve been implementing, we should be able to limit the spread. But it is an epidemic disease, so it will increase exponentially in size. The doubling time of the epidemic has been estimated to be six days.

“That means next week we might have 250 cases and the week after we might have 500 and the week after we might have 1000.

“In some modelling that we did, which is not published yet, the peak may be at about 80 to 100 days from the start in Australia, so it could be around June.

“But if we implement a lot more social-distancing measures it could be a lot later and there could be more than one peak as well.”

Despite the focus on social distancing and contact tracing, Thomas says one of the biggest interventions we can make in limiting the spread of disease is also the simplest: thorough handwashing.

“What we’re trying to do is to minimise the number of cases so that later we will have a vaccine where we can actually prevent cases occurring,” Thomas says.

“But right now, a public health education campaign is really important and urgent. Messages like ‘wash your hands’ actually is not enough.

“It needs to be wash your hands for 30 seconds. Ten seconds is hopeless, and that’s what most people do, that doesn’t take much virus away at all. Twenty seconds is better than 10, but with 30 seconds of washing, any virus on your hands will be pretty much gone.

“Saying wash your hands for 30 seconds may seem like a trivial thing, but actually telling the population how to do those basic kind of hygiene things can dramatically reduce transmission and subsequent rates of infection.”

The government has committed $30m to a national communication campaign on coronavirus as part of its COVID-19 package.

In the meantime, cancellation of mass events in the near future is all but certain, says the director of the Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity Sharon Lewin. “Governments don’t do these things lightly,” Lewin says. “They come at enormous inconvenience to everyone and cost.

“Social-distancing measures used to be quite controversial, and it was unclear that they really worked. But in Wuhan and Hubei, it definitely worked.

“I think what the overall policy is aiming to do is to flatten the peak. And if we do that, we will continue to get new cases but we won’t get a massive increase in cases — that’s the hardest thing to deal with.”

The ANU’s Thomas predicts the next few months will be some of the most extraordinary times we’ve seen in living memory, and people need to prepare for the idea that the way they live their lives may be temporarily different. That means staying at home more often and curtailing travel.

“I’m not telling people what to do. They need to determine their own appetite for risk,” he says. “But I am making bookings in November. That’s my personal view.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout