For 40 years John Lennon’s killer has sought the world’s forgiveness

Obsessed by JD Salinger’s famous novel, Mark Chapman saw himself as its main character and on a mission.

For 40 years Mark David Chapman has sought forgiveness for one of the most bewildering crimes of the 20th century – the murder of John Lennon. As with the assassination of John F. Kennedy 17 years earlier, the killing stunned the world, uniting it in anger.

Most assassins’ motives are clear – he (other than Rajiv Gandhi, murdered by a Tamil Tigress, men largely do this dirty work) has a score to settle, a grievance, or perhaps an ambition thwarted by the existence of his target.

Lennon’s killer was as unlikely an assassin as Lee Harvey Oswald and, as it had in 1963, the world’s attention soon turned to Chapman, his life and crime.

It was 40 years ago on August 24 that Chapman pleaded guilty to killing Lennon and was sentenced to a modest 20 years’ jail (that same year American killer Dudley Wayne Kyzer received two life sentences plus 10,000 years for murder). Australian judges are regularly as generous as the one who sentenced Chapman, but US sentences often come with a valuable catch.

Chapman was a valueless attention seeker from his early days. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, he went to school in Decatur, Georgia, a vibrant area of employment and opportunity. An indolent underachiever, he found it easier to believe his god would think well of him if he reciprocated, rather than study and work to make something of himself. He dodged classes, took drugs and imagined a world in which he was a godlike force – the boss.

He claims to have been “born again” in 1971, aged 16, studied the Bible and worked as a counsellor at a YMCA summer camp, where he was reportedly valued by colleagues.

About this time a friend recommended Chapman read The Catcher in the Rye, the subject of which, Holden Caulfield, is self-obsessed, angry and aimless. Its author, JD Salinger, might have described himself similarly until shortly before he wrote the book for which he is remembered. (Salinger’s already odd life took dramatic turns in quick succession starting in 1942: he dated Eugene O’Neill’s daughter, Oona, who left him to become the last wife of Charlie Chaplin; he submitted short stories to The New Yorker – all rejected; after Pearl Harbor he was drafted into the army, stood on Utah Beach on D-Day and was at the Battle of The Bulge and the liberation of France, where he met his hero, an impressed Ernest Hemingway, who was told of plans for a play about Caulfield in which Salinger would star; he helped out at the Nuremberg trials and married a French-German ophthalmologist, Sylvian Welter, having the union annulled when, it was claimed, he discovered Welter had been a Gestapo informer. He finally completed The Catcher in the Rye in 1951 and it has sold 70 million copies.)

Chapman fashioned himself as Caulfield. It wasn’t hard. Salinger’s antihero is young, dispirited, unambitious, isolated and bitter. Chapman was all that, with a darker soul. Caulfield spends chapters hanging around Central Park, not far from The Dakota apartments that would become the Lennons’ home in 1973.

It is not certain at which point the Bible-obsessed Chapman decided Lennon’s comments to reporter Maureen Cleave about Jesus Christ first rankled him. Lennon invited Cleave to his Weybridge mansion in Surrey’s so-called stockbroker belt – in whose attic he wrote I Am The Walrus and Lucy in The Sky With Diamonds – to speak about his life. The story appeared in London’s Evening Standard under the headline “How does a Beatle live?” on March 4, 1966, and passed without comment in Britain, a nation mostly capable of a mature conversation about religion. “Christianity will go,” said Lennon. “It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now.”

Unremarkable observations, they remained dormant until an American teen magazine called Datebook picked up the out-of-context quotes. The same issue of Datebook ran a readers’ poll: The Ten Adults You Dig/Hate the Most. That may be the puerile fare typical of such publications; nonetheless, its young readers’ responses were insightful – perhaps disturbing. Among the popular adults was evangelist Billy Graham, a manipulative anti-Semite with an equivocal history with America’s civil rights movement. Those Datebook’s young readers hated most included Martin Luther King. The result was certain. Southern DJs labelled Lennon’s comments “blasphemous” and sponsored a “Ban the Beatles” campaign in which, like scenes from the dystopian Fahrenheit 451, the band’s records, books and posters were burned in the streets by stomping, wild-eyed children.

Chapman, a southerner, understood this unhinged rage. While he was always obsessed with Lennon, he slowly came to believe that his hero stood between him and a fulfilled life of fame.

After a chequered work history with World Vision and as a security guard, he moved to Hawaii in 1977. He secured several jobs there, but personality conflicts sometimes saw him unemployed.

While planning a trip to Asia, Chapman and a travel agent, Gloria Hiroko Abe, developed a friendship that, on his return, evolved into a relationship and marriage. “God sent my husband Mark to me in March of 1978,” is how Gloria describes it. He was “kind, generous, sweet, thoughtful and very smart”. (She was approached for this story, but declined to comment, always running such requests by her jailed husband.)

Over time he changed, and would get drunk and assault her. The Lennon obsession was never far off. It was reported that Gloria woke one night to the sound of a Beatles song and her husband shouting along:

“The phony must die, says the Catcher in the Rye.

The Catcher in the Rye is coming for you.

Don’t believe in John Lennon.

Imagine John Lennon is dead, oh yeah, yeah, yeah. Imagine that it’s over.”

That idea became his mantra, and the mission more pressing.

On October 23, 1980, Chapman signed off for the last time from his job as a security guard, doing so as “John Lennon” – and then striking that out. He went to J & S Sales gun shop and bought a five-shot Charter Arms .38 Special revolver from owner Steven Grahovac for $169, needing to show only a driver’s licence to do so.

Grahovac received a dozen death threats after Lennon’s murder. “We sell quite a few guns. It was just a normal gun sale. Nobody knows he’s a schizo,” he said.

On October 30, Chapman flew to New York to kill Lennon. He checked in at the Waldorf and explored the local area and the Dakota, but his plans were upended when he discovered that in New York bullets are sold only to registered gun owners. On returning, he confessed to Gloria the purpose of his trip and produced the weapon he had planned to use and made her hold it. “(It) was still cold from being in the plane’s cargo hold. Very cold,” she remembered.

With five deadly hollow-point rounds, Chapman packed up and left again for New York on December 6, telling Gloria he needed to do so to mature as a man. “He needed time to think about his life,” she told a Hawaii newspaper last year. “He wanted me to sacrifice a short time of being alone so that we could have a long, happy marriage together.”

Arriving on the Saturday, Chapman bought a copy of Lennon’s latest album, Double Fantasy, another copy of The Catcher in the Rye, and made his plans. On the Sunday he waited hours outside the Dakota, but the Lennons stayed in. Heading off, he went to the nearby subway station and bumped into singer-songwriter James Taylor, who lived up the road. Taylor clearly remembers the encounter: “He pinned me to the wall, glistening with maniacal sweat, and tried to talk in some freak speech about what he was gonna do, and stuff about (John Lennon).”

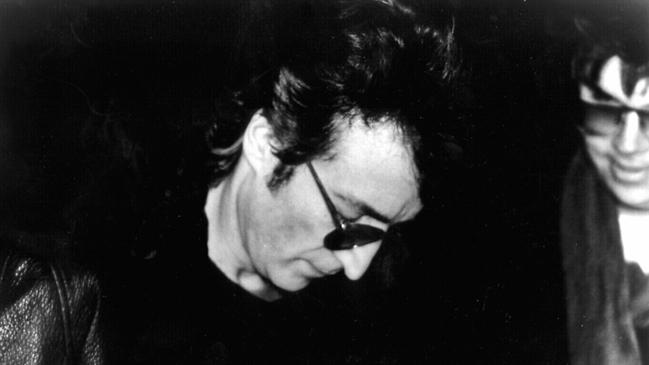

On Monday, December 8, Chapman was back at the Dakota. Spying Lennon’s five-year-old son, Sean, on the street, he reached in front of a nanny to shake the boy’s hand. By 5pm Lennon had been handed Chapman’s copy of Double Fantasy and the famous photograph of Lennon signing his life away was snapped. Returning with Yoko from a session at the Record Plant just after 10.50pm, Lennon stepped out of their limousine and walked towards the Dakota. Chapman seized his moment, after which he leant back and thumbed the pages of his novel.

Gloria was at home watching Little House on the Prairie when a news alert ran across the bottom of the screen stating Lennon had been shot. “I just knew it was Mark.”

Chapman, a calculating man, then turned his efforts to getting away with the murder. He pleaded not guilty “by reason of mental disease or defect’’ at his first court appearance. His lawyer said he would be able to prove his client was insane. A dozen psychologists interviewed the killer: those hired by the defence all finding him insane; those working for the prosecution, and for the court, finding him fit to face trial. One expert brought copies of Salinger’s book for Chapman to sign.

Meanwhile, Gloria appeared at a press conference to discuss her husband, but one answer jarred: “I am just very, very sorry that this had to happen to Yoko Ono and her family, that her husband had to die.” Surely, only Gloria’s husband believed Lennon had to die.

By June 22, 1981, Chapman’s god had instructed him to plead guilty. There was no trial. Two days later he was sentenced. He asked to read a statement, and quoted from yet another copy of Salinger’s book: “I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around – nobody big, I mean – except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff – I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all.”

After sentencing he was transferred to Rikers Island jail leaving his book on the bench.

Chapman, 66, is still married and his wife visits him for 44 hours a year at his new home at Wende Correctional Facility in upstate New York where he is in maximum security and a fellow guest is Harvey Weinstein. He no longer listens to the Beatles, preferring Christian songs.

His sentence was “20 years to life”, a clever device that gives the state the upper hand. Professor Mirko Bagaric, dean of law at Swinburne University, is envious of the American system that allows victims an ongoing say in justice. While we must pass special legislation to keep the likes of Hoddle Street mass killer Julian Knight behind bars, the US system is more flexible. “It is a much more nuanced and fairer system than ours,” he said at the weekend.

Chapman’s two decades is long up, and every two years he can appeal to the New York Board of Parole for his freedom, and does, sometimes with different explanations for the murder, most recently, in August last year, his 11th application, stating: “I have no excuse. This was for self-glory. I think it’s the worst crime that there could be to do something to someone that’s innocent.”

As always, Ono has countered stating her fears for the safety of Lennon’s sons, Sean and Julian, adding last time that she also worried about Chapman’s safety outside, a concern the parole board shares.

At last year’s hearing Chapman said he deserved the death penalty. There are plenty of Lennon fans who agree. And, going by the mail Chapman still receives, many are ready to impose it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout