The day John Lennon really died

John Lennon was murdered 40 years ago, but artistically he was already long gone.

John Lennon didn’t need an autopsy report to know when and how Elvis Presley died. “Elvis really died the day he joined the army,” Lennon said on August 16, 1977, when news of Presley ricocheted around the world. “That’s when they killed him, and the rest was a living death.” By Lennon’s reckoning Presley, conscripted to the US Army on March 24, 1958, had been “dead” almost two decades.

Lennon was shot dead by nowhere man Mark David Chapman on December 8, 1980. Chapman had been born in Fort Worth, Texas, days before Presley’s only visit to the town on May 29, 1955. But it was Lennon with whom he became obsessed.

And, like Presley, by the time he was murdered Lennon too had been in a state of living death. Lennon “died” on Tuesday, August 31, 1971. That morning he and wife Yoko Ono flew from Heathrow airport to New York. Lennon would never set foot in England again. He was almost artistically lifeless from then on.

He’d just had back-to-back top 10 singles with Instant Karma! and Power to the People and as part of the Beatles, Lennon had had 21 No 1 singles in the previous eight years. In his nine New York years he would have one.

By the time he touched down in New York and made his way to the St Regis Hotel on East 55th Street that last day of summer, Lennon’s creative genius has dried up, his eccentric lyrical brilliance was exhausted and his enthusiasm for music would soon give out.

He would write a handful of worthy, if derivative, songs, retire to be a “house husband” for five years and return with a thin, patchy comeback album that would stall outside the top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic (it fell from 14 to 46 in a single week in Britain) before bursting back to sell millions, top the charts across the globe and win a Grammy for album of the year.

That was his killer’s doing and our mawkish response.

But as a songwriter Lennon had shot his bolt. Nothing he did beyond August 1971 was vital, important or even counted. He ended up almost a caricature of the Beatle he hated most at that time: Paul McCartney. You want Silly Love Songs? I’ve got ’em. His luminous, sometimes dazzling songwriting skills would work across just two post-Beatles albums and then were unaccountably extinguished.

Under the influence of Ono, Lennon’s early solo efforts were unlistenable. With the benefit of a half-century’s hindsight we now understand them to be worse than that. At her best, Ono “singing” sounds like someone strangling a cat. Lennon may have thought of it all as experimental, perhaps even avant-garde, but it is worth noting that in the long tradition of the vanity press the albums were issued by the Beatles’ label, Apple. It wasn’t music and no one liked the noise it made.

In a gimmick to encourage sales, the cover of Lennon’s first solo album, Unfinished Music No 1: Two Virgins, was a picture of Lennon and Ono naked. But who wanted to see them naked? Certainly not Sir Joseph Lockwood, chairman of EMI which pressed and distributed Apple records. He had met the Beatles and a fifth person a few weeks earlier to discuss business matters. “When the four boys came they had with them this person all in white, surrounded by hair, and I couldn’t see anything. I wasn’t sure if it was a human being.”

Weeks later the woman in white was back in Lockwood’s office with her new husband. McCartney also was along to “keep the peace”. Lennon showed Lockwood the nude photo. Lockwood said he’d seen worse and Lennon fired back “So, it’s all right then, is it?” Lockwood said it wasn’t. Ono pushed back, insisting: “It’s art.” Lockwood became irate. “Well, I should find some better bodies to put on the cover than your two. They’re not very attractive. Paul McCartney would look better naked than you.” McCartney blushed.

In a world with an apparently endless appetite for anything Beatles, someone, somewhere probably knows the names of everyone who bought Two Virgins. It failed to chart in Britain and peaked ingloriously at No 124 on Billboard.

Lennon knew a good song when he heard it. But these weren’t songs. They were … well, who knows really? But the follow-up was already on the way. Unfinished Music No 2: Life with the Lions came next and included the foetal heartbeat of their soon-to-be-miscarried son, John Ono Lennon II. It also failed to chart in Britain and fell 50 places short of its predecessor — at 174 — on Billboard. Things couldn’t get worse for the much-loved Beatle. But they did. Lennon’s third effort, Wedding Album, made little sense but came lavishly packaged and was heavily promoted. It also failed to chart in Britain and limped to 178 on Billboard.

Lennon then did the unexpected. While Ono was distracted with a solo recording, Lennon in 27 days, starting on September 26, 1970, recorded one of the most remarkable albums of the rock era — John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. His wife’s contribution is listed in the credits as Ono: wind.

Unshackled for a time, Lennon comes good with a raw set of the most bleak, blunt and scornful songs, a catharsis during which he famously expels the bad spirits of Beatlemania, but only after admonishing his much-loved mother and challenging his absent father. Before his mother Julia’s death in 1958, when she was hit by a car and killed in his street by an off-duty (and unlicensed) policeman, Lennon had been handed over to his Aunt Mimi, with whom he lived his formative years. In so few words, Lennon sums up his family life and the undiluted despair that haunted one of the world’s most famous men.

Mother, you had me, but I never had you

I wanted you, but you didn’t want me

So I just got to tell you

Goodbye

Father, you left me, but I never left you

I needed you, but you didn’t need me

So I just got to tell

Goodbye

It kept company with starkly direct Lennon songs such as Isolation, My Mummy’s Dead and Working Class Hero, the profanities in which prevented it from being broadcast on radio.

It was an unexpected, sincere triumph that took Beatles fans by surprise — and years to be fully understood — but it was a top 10 album everywhere. All albums by former Beatles sold well — unless Ono was involved. Rolling Stone magazine rated the album fourth on the list of the 100 best albums between 1967 and 1987. In 2003, Lennon’s album came 22 in its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, and in 2006 the album was chosen by Time as one of the 100 best albums of all time.

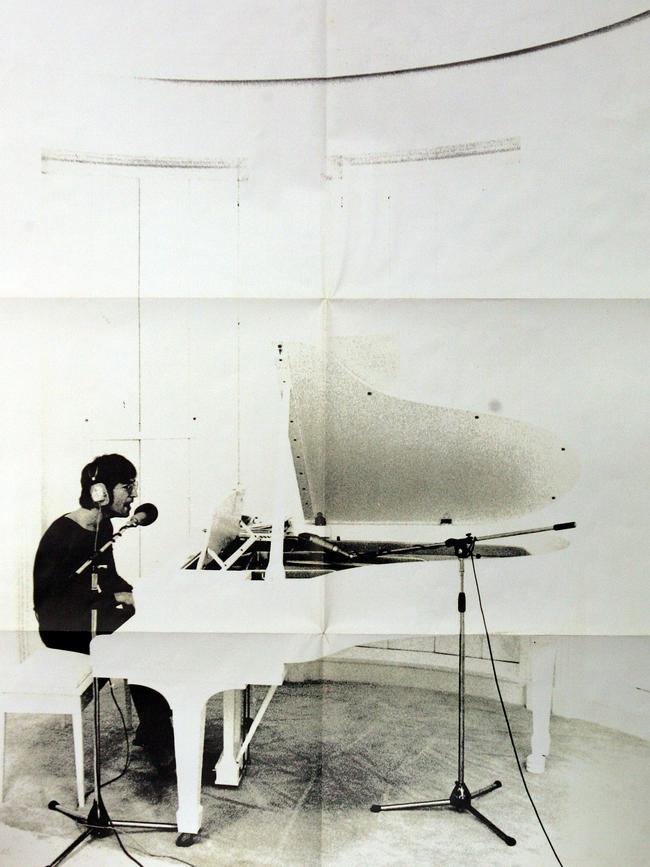

Lennon responded within a year with his most loved album, Imagine. The hymnlike title track is still sung the world over. Liverpool’s international airport has be renamed Liverpool John Lennon Airport. On its ceiling are the words “Above us, only sky”.

Imagine was slipshod — Lennon was always impatient with the recording process — but with musicians such as George Harrison, Nicky Hopkins, King Curtis, Jim Keltner and Jim Gordon on board, it is more musically appealing than its predecessor. Side one’s Jealous Guy, a reworked Child of Nature from the White Album era, could easily have given the album its second No 1 hit, as Roxy Music proved a decade on. Elsewhere, Lennon’s songs lashed out at lying politicians, war, his then songwriting nemesis McCartney in the lacerating How Do You Sleep?

Weeks after Lennon arrived in New York the Imagine album topped the US and British charts. In the US Lennon busied himself with a dozen radical issues including the jailing of radical poet and activist John Sinclair, women’s liberation, Ireland’s insoluble Troubles and the Attica state prison riots.

And on his next album he recorded his opinions with a sort of musical newspaper, packaging itself in the style of The New York Times. Some Time in New York City bombed. Rolling Stone’s Stephen Holden summed up the problems: “The Lennons should be commended for their daring … The tunes are shallow and derivative and the words little more than sloppy nursery rhymes that patronise the issues and individuals they seek to exalt. Only a monomaniacal smugness could allow the Lennons to think that this witless doggerel wouldn’t insult the intelligence and feelings of any audience.”

The album was a double; the second disc recording some live moments in London and with Frank Zappa is best not discussed.

A year later came Mind Games, the title track another reworked idea from Beatles days. It is another simple message about love triumphing over war, not that it resolves itself. It didn’t go anywhere, other than No 16 in Australia, No 18 on Billboard and No 26 in Britain.

The first side ended with the Nutopian International Anthem — Lennon and Ono had recently established the fictional nation of Nutopia. The track was three seconds of silence. Lennon, already running out of ideas, was now running out of music.

New Musical Express writers Roy Carr and Tony Tyler stated that Mind Games “bears all the hallmarks of being made without any definite objective in mind — other than to redeem the unpleasantness of Some Time in New York City”.

The Walls and Bridges album was a patchy return to form. With Elton John on piano, organ and backing vocals, and Bobby Keys’s best sax solo since Brown Sugar, Lennon had a chart-topper with muscular Whatever Gets You Through the Night. What was meant to be the title track kicked off side two. The song had come to Lennon while he slept so he renamed it #9 Dream, and its woozy, off-centre orchestration felt very much like I Am the Walrus from back in the day when his eccentric, nonsensical lyrics demanded attention.

The last, laziest resort of all spent musicians is the covers album reinterpreting songs from their youth. McCartney has done one; Ringo Starr too. John Farnham recorded his favourite Australian hits; the redoubtable James Taylor has just released one; and no one has been able to stop Rod Stewart from doing album after album of them.

But Lennon’s Rock ’n’ Roll album may have been the first. We loved those old songs — Be Bop A Lula, Stand By Me and Ain’t That a Shame — but Lennon’s journeyman attitude to them rendered the project pointless.

He retired, baked bread, walked in Central Park and attended to his new son, Sean. He stopped playing guitar, stopped writing songs and abandoned music.

But during a long break in 1980 on Bermuda with young Sean, Lennon started writing songs again. He called Ono with the news. She too decided to write some songs. Ono? Oh, no.

On returning to New York he started recording what became Double Fantasy. The first single from it, (Just Like) Starting Over — arranged and sung in a style pitched somewhere between Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley — was keenly anticipated and rose to No 6 in the US. It hit No 8 in Britain before slipping down to 21.

Almost invariably, critics shunned Double Fantasy, particularly Ono’s annoying contributions. Lennon’s comfortable songs about his agreeable domestic circumstances hit the wrong note with reviewers.

Legendary British rock writer Charles Shaar Murray, a big Lennon fan, wrote: “It sounds like a great life, but it makes for a lousy record … I wish Lennon had kept his big happy trap shut until he had something to say …”

Perhaps it was too close to the “granny music shit” Lennon loathed about McCartney’s sometimes twee compositions. Until December 8, Double Fantasy was about to belly flop into the pool of also-ran albums of 1980.

But wheels were moving within wheels. On the night of December 7, Taylor, who’d recorded for Apple and was still friends with Lennon, living one door up from the Dakota building outside of which Lennon was murdered, was confronted by a hyperactive nutter in the New York subway’s 72nd Street Station.

“(He) had buttonholed me in the tube station … He pinned me to the wall, glistening with maniacal sweat, and tried to talk in some freak speech about what he was gonna do, and stuff about how John was interested and how he was gonna get in touch with John Lennon.”

The next night, Taylor was at home on the phone speaking to his manager, Peter Asher’s wife, Betsy. (Asher had been half of the duo Peter and Gordon, which had the worldwide hit World Without Love, a Lennon-McCartney song. McCartney’s girlfriend at the time was Asher’s sister Jane. Peter Asher had signed Taylor to Apple in 1968.)

“(Betsy) was in Los Angeles and she was complaining that things were getting very crazy there … Something was happening to do with the Charles Manson family. Then I heard these five shots … bam-bam-bam-bam-bam. I said, ‘You think it’s crazy out there. I’m just listening to the police shooting somebody down the street.’ We rang off. Then about 20 minutes later she called me back, and said, ‘James, that wasn’t the cops.’ ”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout