Existential dilemma: the great conservative split

With the Trump revolution wreaking havoc on conservative movements worldwide and the election rout leaving Liberals stunned, Australian conservatism faces an identity crisis it no longer can afford to ignore.

In the aftermath of last weekend’s devastating election loss it is easy to write off conservatism in Australia. This wouldn’t be for the first time. As historian Keith Hancock observed in Australia (1930), conservative, in this country, has always been a term of abuse, implying that its target is an out-and-out reactionary.

There is nonetheless a profound paradox. Although conservative may be a term of abuse, Australian politics has long had a marked conservative vein, even as its chief protagonists have studiously avoided the descriptor. A hardy perennial, with a distinctive voice that contrasts with overseas conservatism, the conservative instinct in Australia has run deep, dominating federal politics for decades – and recovering, time and again, from setbacks that had been claimed to foreshadow its demise.

Now, however, with the Trump revolution wreaking havoc on conservative movements worldwide and the election rout leaving Liberals stunned, Australian conservatism faces an identity crisis it no longer can afford to ignore. Understanding its divergence from overseas traditions is vital to recovering and redefining the distinctive voice it needs to deal with the latest threat to its existence.

In part, that identity crisis reflects the factor that has made for conservatism’s enduring success: its infinite adaptability. Indeed, the term defies easy definition, just as the groups to which it has been applied defy ready categorisation, making the conservative identity inherently labile.

As Paul de Serville, a historian of Australian and British conservatism, has observed, every party that has emerged to represent conservatism’s interests and beliefs across the past 350 years “is a study in contradiction between opposing traditions and schools of thought”.

Even its founding parent, the movement that eventually became the Conservative Party in Britain, has “died or lain dormant” numerous times, split at least twice, and never settled on any singular set of policies, ideas and beliefs. Its capacity to incorporate diverse elements has in fact been one of its defining qualities. After all, “what other party has elected a Jewish novelist (Disraeli) to lead a group of wordless squires? Or a grocer’s daughter (Thatcher) to rule a sulky band of Tory Wets?”

But beneath the shifting terrain of cultural and political battlegrounds, there are in British conservatism some identifiable commitments. Originally, the commitment was above all to tradition. Born in the turmoil of the English civil war, the Tories (a term derived from the Middle English slang for outlaw) stood for loyalty to the Church of England and the crown. Unapologetic royalists, their clergy defended the church against the Puritans while stressing the values of family, home and nationhood. Over time, however, the primary emphasis of British conservatism changed into a commitment to the virtue of prudence.

Often associated with a sense of human limitations and the impossibility of achieving utopia, British conservatism became the embodiment of a Western intellectual tradition that extends back at least as far as St Augustine.

Conservatism in the US had a starkly different origin and trajectory. Far from being a reaction to the threat of change, it was a by-product of the American Revolution’s fight against the crown. Initially, what it sought to conserve was the ideal of a “mixed constitution” whose myriad checks and balances could prevent the development of an overmighty state. That coexisted with the agrarian conservatism of the south that feared, above all, the centralism that might abolish slavery and privilege northern manufacturers over southern primary exporters. Together, those foundations fuelled the development of a staunchly conservative, often highly formalistic legalism whose power – unrivalled in any other Western country – grew with the ascendancy of the Supreme Court.

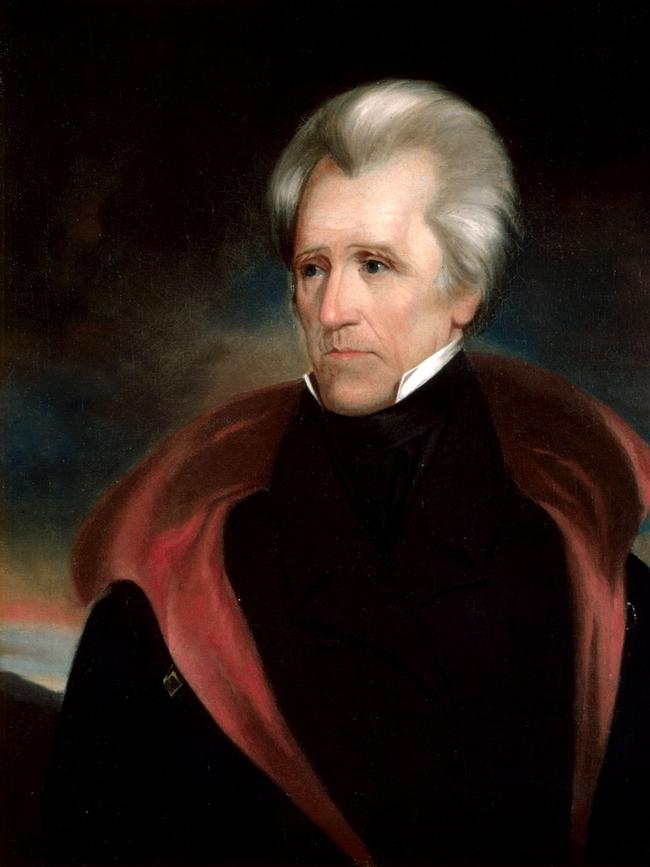

But as early as the 1820s that version of conservatism faced a powerful challenge from Andrew Jackson’s radical populism. Jacksonian populism had more than its fair share of incoherence but its grassroots pugnacity spawned one of US politics’ most enduring and certainly most distinctive notions: the spectre of a “deep state” that was liberty’s greatest enemy.

Permeated by a Manichean friend-enemy dynamic that distinguishes what American historian Richard Hofstadter famously called the “paranoid style” in US politics, the Jacksonians portrayed the federal government as far worse than overbearing: having been hijacked by the enemies of the common man, it was an actively malevolent force hiding behind the facade of law and order. Only by dismantling it could freedom be preserved.

The Jacksonians left a deep imprint on the American right and most notably on its rhetoric, but they never entirely conquered the field. The somewhat rigid constitutional conservatism that had preceded Jacksonianism survived and, inspired by intellectual leaders such as Supreme Court associate justice Antonin Scalia, flourished.

At the same time, many other varieties of conservatism appeared and at times reappeared after having gone into abeyance.

For instance, Vice-President JD Vance’s commitment to an intensely moralistic vision of politics – that privileges honest labour over endless consumption, security at home over adventures overseas, family and local community over wider notions of society – renews a Catholic tradition that had waned as the ethnic communities that were its original bearers assimilated into the American mainstream.

In that sense American conservatism was always as mutable, open-ended and diverse as the US itself. But for all of that diversity, the nature of the presidential contest periodically forced its differing elements to coalesce around a leader who somehow embodied the spirit of the times.

Seen in that perspective, Donald Trump’s ascendancy reflects the triumphant resurgence of the movement’s radical populist streak.

As with all populisms, Trump’s message jumbles together contradictory, even irreconcilable, components. But it isn’t intended as a coherent intellectual project – it is not a politics of ideas that Trump pursues but of emotive response and instantaneous impact.

Even less is it a politics of cautious pragmatism, as was the conservatism of Republicans George HW Bush or John McCain, who also channelled one of American patriotism’s many styles. And least of all is it, like Vance’s, a politics of high moral purpose. Rather, it is a politics of personal power, deployed, often arbitrarily, to purposes that can change unpredictably from day to day.

That it is not to deny that there runs through Trump’s project American conservatism’s golden thread: the goal of restoring what his supporters view as the freedoms that were the original promise of the American founding and, later, the American Revolution.

But much as was the case with the Jacksonians, that goal is to be achieved by demolishing existing institutions, which are cast as having betrayed the original promise, rather than through their cautious reform. Trumpism’s intensely antinomian character is starkly antagonistic to the American tradition of constitutional conservatism, which is why a number of unquestionably conservative scholars are challenging the administration’s actions in the courts. At the same time, its messianic quality, imbued with visions of future glory, breeds a fanaticism entirely alien to the British conservative tradition.

It is entirely alien to the Australian conservative tradition too. Here the greatest difference lies in the fact the Australian political ethos has not seen the state as the enemy, much less as a malignant force. It has been regarded instead as a tool to be effectively used to benefit the people and help them flourish.

That difference from the US has profound historical roots. America’s initial European settlement occurred in the 1600s, a period distinguished in Britain by what became known as the “Old Corruption”. Government offices were chiefly sinecures, officially apportioned rackets for personal gain, propping up an oligarchy whose favours were openly for sale.

In contrast, European settlement in Australia and New Zealand began as sweeping reforms to Britain’s system of government were taking hold. For the first time it was becoming possible to treat the government as a utility, dispensing valued benefits, rather than as a lurking predator. Colonial governors’ administrations, while not without their own rackety aspects, were shaped by changes reducing royal patronage and improving government accountability. As Australian historian John Hirst argued, that laid the seeds of an enduring respect for impersonal authority, exercised, at least in theory, in the pursuit of prosperity and good order.

There were, for sure, periodic outbreaks of radical opposition. But the Australian approach was almost always to absorb the conflict by institutionalising its protagonists. Embedding the agitators within the system they were fighting against, that solution traded moderation for tangible gains.

For example, violent class war and mass strikes in the 1890s Depression culminated in the birth of the ALP as an official parliamentary party, changing laws and winning government. Later, the Arbitration Court became run largely by what had been the warring parties – the infamous “industrial relations club”, as columnist Gerard Henderson called it. In exchange for prestigious sinecures, the former enemies descended into what Hancock derided as a “pettifogging” legalism that suffocated the radicals.

Equally, landless gold-diggers demanded the squatters’ leases be ripped up, and stormed Victoria’s parliament in the 1850s. The Land Selection Acts in the subsequent decades established a regional population of often struggling farmers whose 20th-century political incarnation took the form of country parties.

Those parties not only secured “protection all round” in the 1920s, along with significant direct subsidies; they also ensured the establishment of marketing boards to which party worthies were invariably appointed. And much the same could be said of the Tariff Board, which shaped manufacturing protection for decades.

The corollary of that solution was a particular type of conservatism. Yes, in the early years of settlement there had been “real” conservatives of the Tory variety. But when self-government began, they were rudely jostled aside. Australian conservatism would not draw its strength from them.

It was instead the middle class that provided the dominating motifs of enduring Australian conservative strength. It isn’t difficult to understand why. The “workingman’s paradise” was a place where ordinary settlers and working men could get ahead, not rags-to-riches style, as the American dream pitched it, but enough to acquire comfort, leisure and independence.

Australian wages had been essentially the highest in the world since first settlement and the political victory of liberalism, which occurred during the 1850s gold rushes, ensured free markets and social mobility. To become an independent small business owner, to own your own home, to provide for your family, your children – this was the dream, and in Australia they by and large found it.

The conservatism that resulted from that success story incorporated the liberal beliefs and practices that proved so decisively triumphant in the colonial context. Historian Zachary Gorman observes that liberalism’s 19th-century victory in Australia was so comprehensive it became “less of a clear agenda and more of a pervasive political culture”. No longer conservatism’s upstart challenger as in Britain, liberalism here almost instantaneously became the established mainstream – it became what needed to be protected, as well as what conservatives sought to conserve.

Australian conservatism, then, sprang not out of reverence for the past or social hierarchy but from attachment to the enjoyments and freedoms of ordinary life that the most liberal polity in the world encouraged to flourish. It kept faith with ordinary experience and the socially durable values of an open society.

It soon came to shape the whole of the centre-right, underpinning both the twin liberal traditions of early 20th-century Australian life – the neo-Gladstonian free trade liberalism typified by NSW’s Henry Parkes, George Reid and Joseph Carruthers and the Deakenite liberalism protectionist Victoria championed.

More pragmatic and willing to innovate than, say, Britain’s Home Counties conservatism, Australian conservatism was dispositional rather than traditionalist – as a byproduct of urban, aspirational, middle-class Australia, generally inspired by the hope of improvement, it had no difficulty accommodating an uninterest in the past. The attachment to steady improvement was the important thing.

Robert Menzies’ pitch in his justly famous “Forgotten People” broadcast in 1942 captures this spirit perhaps better than any other significant Australian political testament. In it Menzies speaks directly to the attachment to the home and the family as the cornerstone of the “real life of the nation … in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and who … see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race”.

Accompanying that emphasis on home and family is a classically conservative sense of continuity.

“It’s only when we realise that we are a part of a great procession,” Menzies declared in laying the foundation stone of the National Library of Australia two months after he retired in March 1966, “that we’re not just here today and gone tomorrow, that we draw strength from the past and we may transmit some strength to the future.”

Across several decades of political leadership Menzies’ speeches pulsed with phrases that exemplified this disposition. His governments have been “sensible and honest”. He speaks “in realistic terms”, sustained “by an unshakeable belief in the good sense and honesty of our people”.

Yet this stress on continuity in Menzies’ rhetoric complemented rather than contradicted a commitment to what he referred to as “solid progress”. This country was a settler society built by successive waves of migrants; since its earliest days, its life had been saturated with optimism: Australia, said Menzies, was “our young and vigorous land”, still embarking on its glad, confident morning.

It was the constant undercurrent of hope and aspiration that gave Menzies’ conservatism its distinctive flavour, making it more explicitly geared to the confident expectation of future possibility than its European or American counterparts.

And it was precisely because it was so oriented to progress that the term conservative was generally avoided by the movement he forged, even as a conservative disposition bubbled along beneath its immediate surface, and was mirrored in electoral preferences of voters – not simply by voting right of centre but by giving governments a second term even if their first had been somewhat disappointing, and by regularly knocking back proposed constitutional changes.

However, those two elements – continuity and change – were uneasy bedfellows: continuity could, and eventually did, act as an obstacle to indispensable change.

The institutionalisation of conflict through entities such as the arbitration tribunals and the Tariff Board had, for decades, moderated conflict – but only at the price of inefficiencies that became ever more unsustainable as the world economy globalised in the 1970s and 80s. At that point, Australian conservatism entered into a prolonged crisis, torn between the deeply embedded value of caution and the equally strong value of adaptation.

It was easy to repeat Edmund Burke’s axiom that “A state without the means of some change, is without the means of its own conservation”; but effecting sweeping change without destroying the party’s unity was of an entirely different order of difficulty.

Nothing more clearly highlighted the dilemma than Liberal leader John Hewson’s Fightback – a call to arms that was as close as the movement ever came to a truly Thatcherite policy revolution. Its failure had many causes but one was the complete absence of the sense of continuity and stability that has always been dear to the Australian middle class.

It lacked, too, the high Gladstonian moral clarity that Margaret Thatcher articulated in her heroic campaign to reverse Britain’s slide to socialised mediocrity. In fact, Thatcher’s argument for the moral basis of capitalism had far more in common with Menzies’ creed of “lifters not leaners” than with Hewson’s “economic rationalism”.

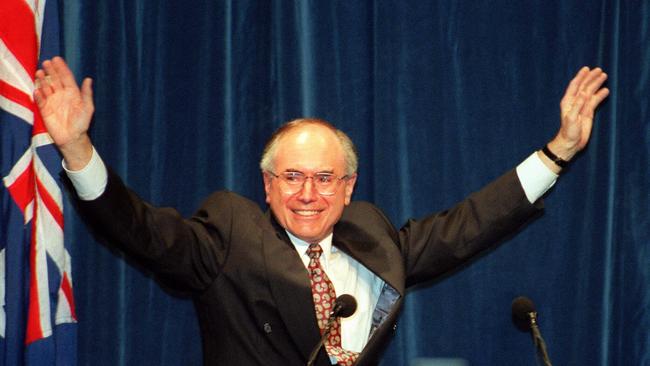

What was needed was a new synthesis. As Menzies had, John Howard, the first Liberal leader to actively identify himself as a conservative, provided it.

Nigel Lawson, who served as the Thatcher government’s most consequential chancellor of the exchequer, once commented that whereas “Harold Macmillan had a contempt for the (Conservative) party, Alec Home tolerated it, and Ted Heath loathed it, Margaret (Thatcher) genuinely liked it. She felt a communion with it.” Exactly the same could be said about Howard: his scrupulous respect for his party’s traditional ethos helped him succeed for as long as he did.

That is not to deny that Howard at times pursued dramatic change – a GST, industrial relations reform, gun ownership – but the approach was rarely radical in style, much less revolutionary in tone. It is telling that the one reform that failed was Work Choices, which went furthest in dismantling existing institutions. And it is telling, too, that subsequent Coalition governments tinkered with the arrangements Labor put in its place rather than seeking their wholesale removal.

Now the synthesis Howard forged between conservation and change is yet again under extreme stress. So, too, are its electoral foundations, as the bases of politics undergo a profound transformation.

Because of Australian conservatism’s pragmatic nature, marshalling broad alliances against those forces and movements that endanger the foundations of the polity has always been its signature approach. Finding some common ground among its constituents, each of those alliances combined the shared opposition to an adversary with a positive program based on overlapping, if not entirely shared, values. The way Liberals, free-traders and protectionists alike rallied alongside Conservatives when threatened by a new common enemy, the ALP in the early 20th century, is a classic example.

However, the dominant force in contemporary politics is fragmentation: the centrifugal pressures that make coalitions hard to assemble but easy to destroy have become ever stronger as social media and identity politics shatter politics’ traditional alignments.

The centre-right is far from being immune from those tendencies, as the emergence of the teals shows. And they are compounded by the pressures of Trumpian populism, which is as hostile to the compromises coalition-building entails as it is to inherited institutions. The only coalitions Trumpism can forge are those that aggregate resentments: against the arrogance of the “progressives”, the abuses of power that occurred during the pandemic, the perception that common values are denigrated and despised.

To use a phrase American constitutional lawyer Greg Lukianoff and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt coined for the left, Trumpism’s dominant mode of action is “common-enemy politics”, with the adversary being the principal factor unifying its disparate parts. There are no shared values, nor any shared aspirations; the glue comes from shared hatreds.

But intransigent oppositionalism is no basis for a viable politics. Regardless of what Trump’s Australian acolytes believe, its transposition to this country would make for a future of repeated failure.

Rather, for a broader alliance to be possible again, a new synthesis is needed. Australia’s two greatest prime ministers, Menzies and Howard, suggest the way. Both exemplified a social conservatism that drew from the distinctively Australian emphasis on the conservative temperament over and above distinctive philosophical creed. Both forged a synthesis that combined an attachment to liberal principles with a commitment to large-scale changes needed to underwrite prolonged prosperity and progress.

Now, after the rout of last weekend’s election, that synthesis desperately needs to be redefined.

In the end, politics is about argument and arguments are about ideas. When politics seems so entirely bereft of them, Australian conservatives have no choice but to think again.

Henry Ergas is a columnist with The Australian. Alex McDermott is an independent historian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout