Even a bogeyman like Russell Brand deserves a fair trial

If you worked in a big law firm or investment bank in the 90s, you’d know some women were treated as sexual meat. Less well known were the names of those who allowed it.

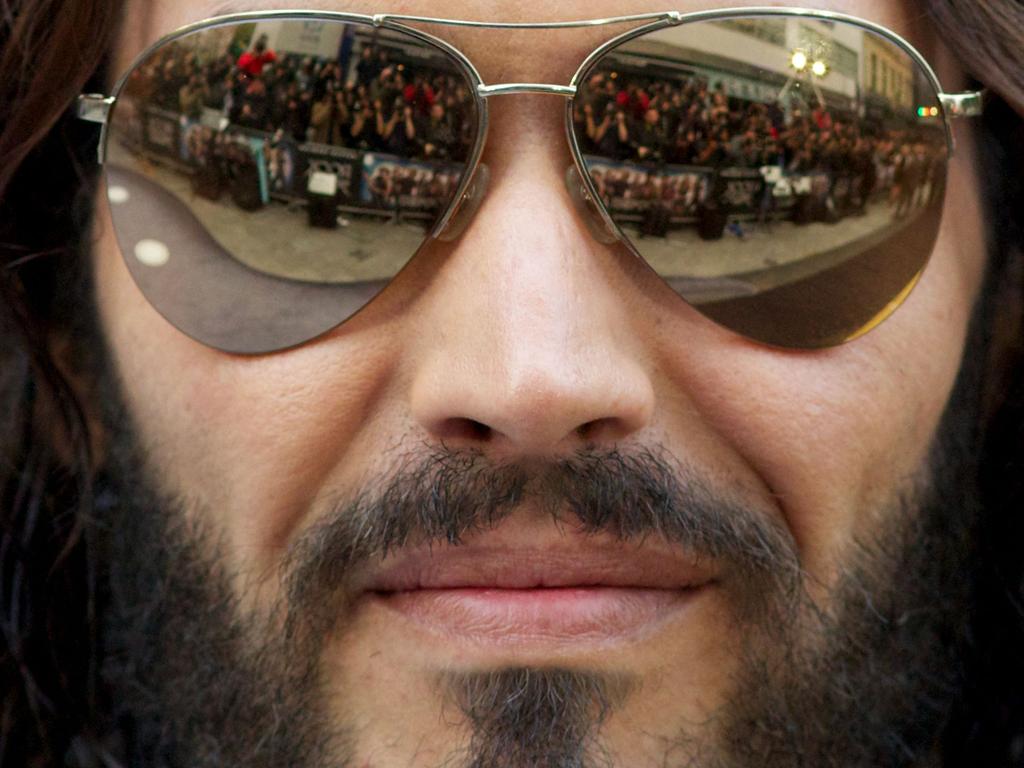

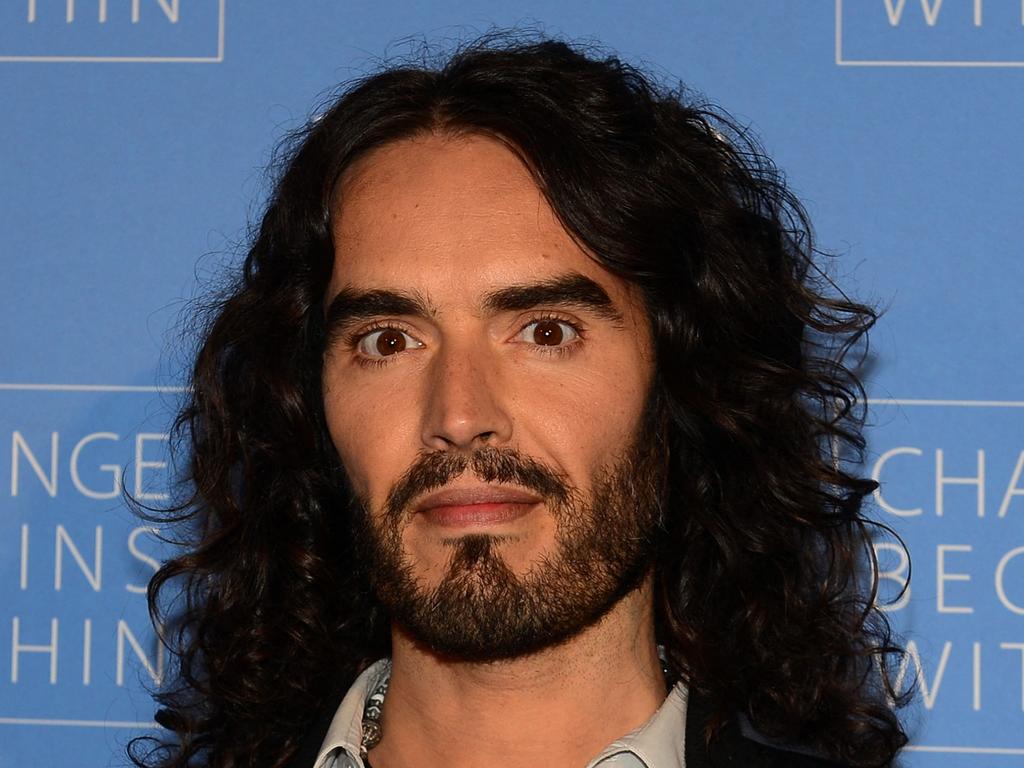

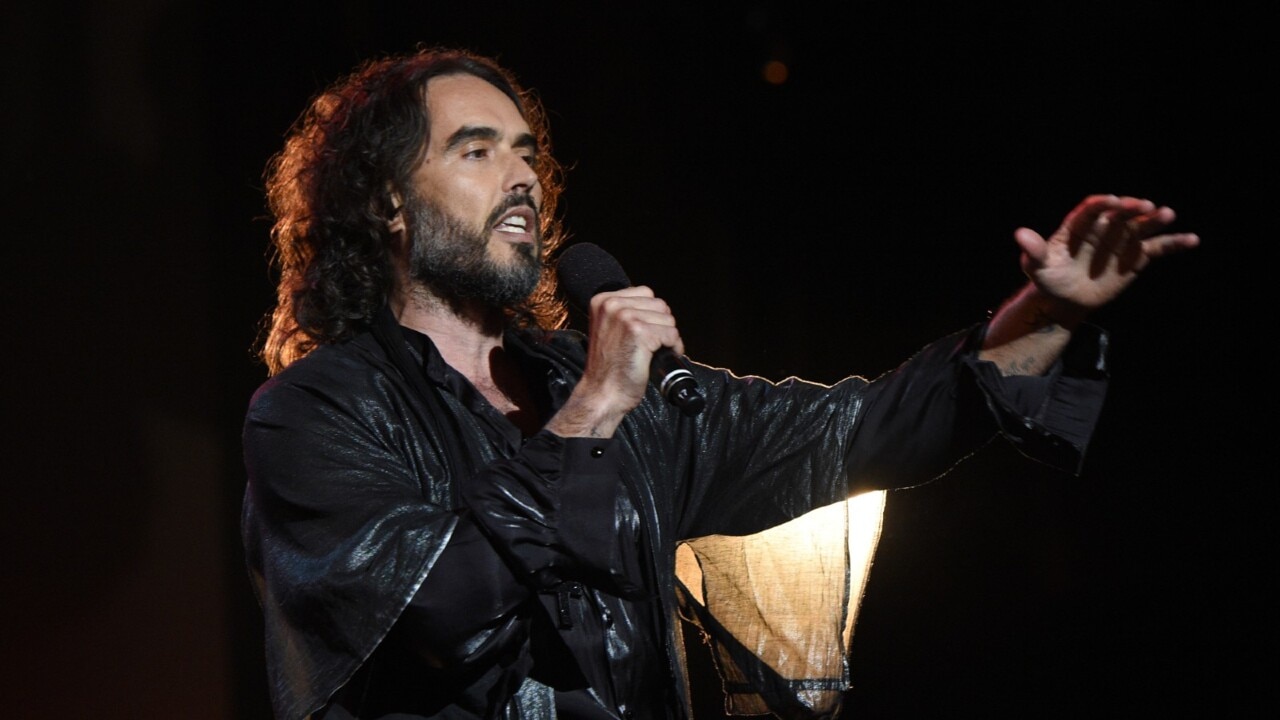

That English comedian Russell Brand has met with his comeuppance is not unwelcome news. The numerous claims of him being a sexual predator and an alleged rapist, his own gross history of bragging about shagging, his transformation from being a Corbynista anti-capitalist to being at home on podcaster Joe Rogan’s show and running alt-right conspiracy theories point to a mercurial man whose past eventually would catch up with him in one way or another.

Few can be surprised that Brand has been accused of serious sexual assault by several women, or that he denies the allegations. This is not an explosive story. That it is yawn-inducingly predictable is why the Brand saga raises important matters beyond his alleged crimes. What is more troubling than the abusers are the enablers. And there are many more of the latter than the former.

If you worked in a large law firm or investment bank in the 1990s, for example, like I did, you would know that some young women occasionally were treated as sexual meat. Not always. Not by all men. But there were times, usually involving alcohol paid for by the firm, where some men – including very senior ones – behaved badly. These men were as well known to junior employees as they were to their more senior peers in the firm.

Less well known were the names of those who allowed the behaviour to continue. Partly, a bit of groping and other sexual shenanigans were seen as no big deal. Plenty of women engaged in, and enjoyed, sexual banter back then too. But there were enough senior lawyers and bankers – male and female – who knew the difference between that and the lewd, unwelcome behaviour of their peers.

There were two categories of enablers who allowed the worst harassers to remain in their senior positions: the low-calibre enablers who turned a blind eye, and other high-calibre enablers who absolutely knew about the behaviour and should have done more to stop it.

Some young women were, at times, bold enough to tell the transgressors – though they were more senior to us – to “f..k off”. But not all young women could do that. All of us had this much in common – we had nowhere to go to complain about a man who, for example, thought it was fine to ask a young employee for oral sex at a work function. If there was someplace to report it, we didn’t know about it.

The allegations about Brand from many years ago point to the fact these young women may have felt they had nowhere to go either. It wasn’t that the media had no interest in learning that a high-profile celebrity was a sexual predator. Establishment media – and the public – facilitated the predator.

Large media organisations encouraged Brand’s tawdry behaviour – they banked on it, paid big bucks for it. And millions of people revelled in his reliable indecency and mercurial political views.

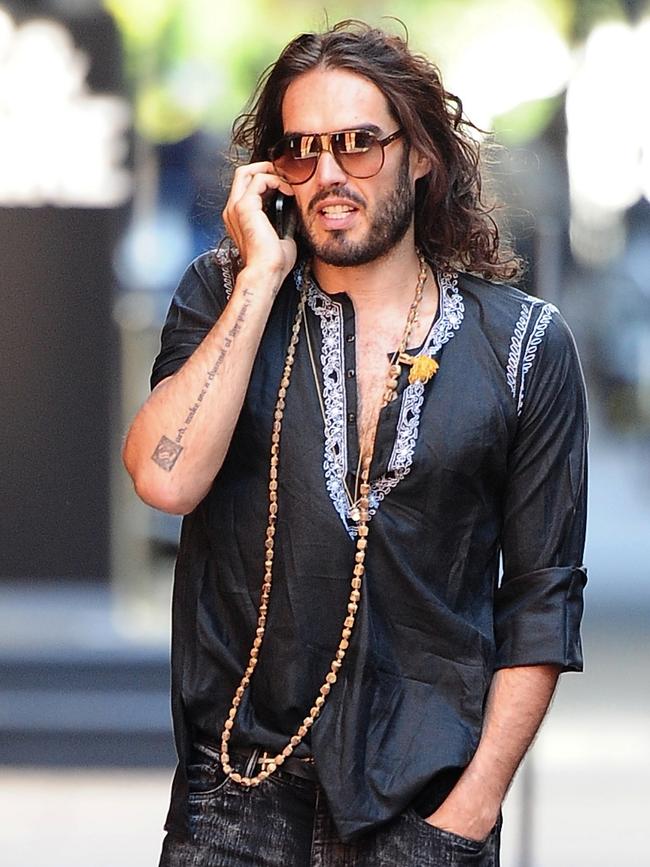

Brand’s particular form of entertainment included pleasuring a gay man in a Soho pub to push his own sexual boundaries, meeting a neo-Nazi and seducing a pensioner.

In 2008, BBC Radio 2 broadcast a prerecorded program where Brand and fellow presenter Jonathan Ross were paid vast sums to laugh about a series of phone message they left on the answering machine of a lonely old actor, Andrew Sachs. The messages recorded threats by the men that they would “kick in his front door” and that Brand had “f..ked” Sach’s granddaughter. They joked about how a grandparent might have a photo of a young grandchild on a swing next to their bed – and how Brand had “enjoyed” Sach’s granddaughter on a swing.

Brand was suspended for that, but his fame was fuelled by other media outlets too, all of them investing in his ugly character.

When he was left-wing, Brand had a column in The Guardian, he was on Channel 4, he was invited to speak to Jeremy Paxman on the BBC’s Newsnight, he was guest editor of The New Statesman.

Sections of our own country were seduced, too. Brand appeared on Ten’s The Project where a female panellist asked him how his recent commitment to celibacy was going. “What time do you finish work?” he shot back. They all guffawed with delight at the boom-boom predictability of this walking, talking sex act. In 2012, Brand grabbed Nine journalist Liz Hayes, kissed her and offered to undo her bra when she interviewed him for a 60 Minutes segment.

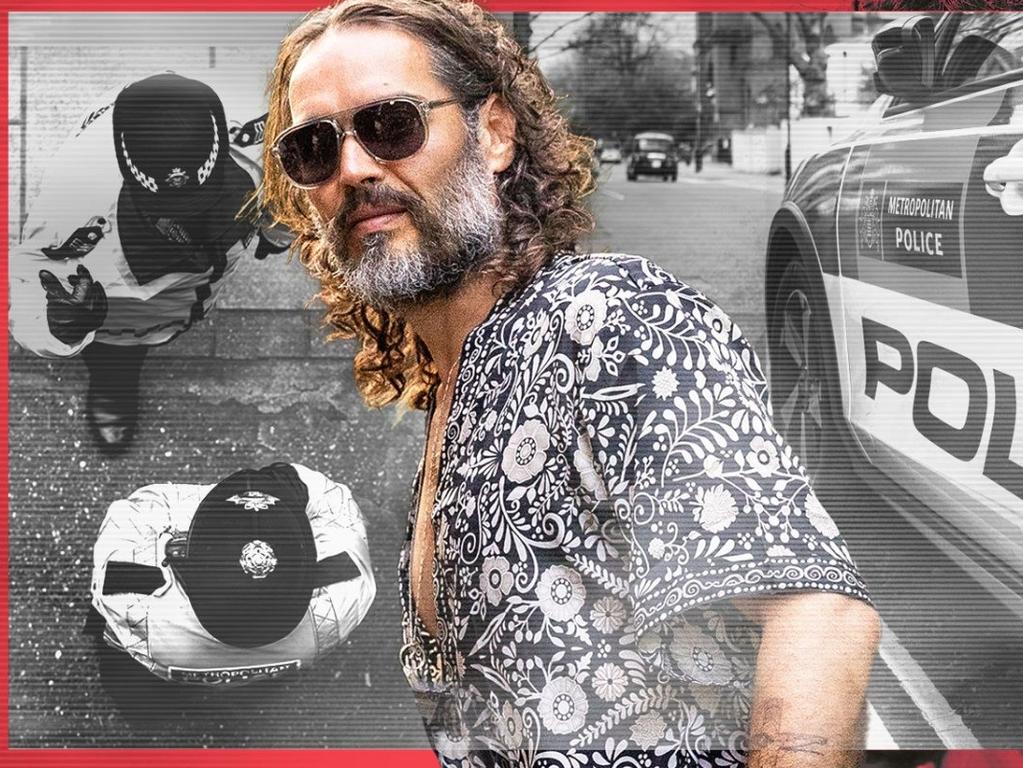

The investigation of Brand by The Times, The Sunday Times and Channel 4 is admirable, painstaking work. And why wouldn’t women go to the media when they can secure instant, albeit rough, justice? The attraction of doing that is obvious if you have spent years staying quiet. But let’s not imagine that those who are part of this new line of reporting, exposing allegations in the media before they are reported to police, are naive to consequences.

Even the most responsible, carefully legalled media investigation into Brand has, once again, given way to a public lynching where a complainant becomes a victim and the presumption of innocence becomes redundant.

Some will say this case is different, that we can head to verdict before a trial because several women, unknown to each other, have made accusations that tend to corroborate each other. But they are still untested claims. And what is the right number of women making allegations against one man that justifies the verdict first, trial later model? Three? Four?

One untested allegation set off a public witch-hunt that enveloped Bruce Lehrmann when Brittany Higgins chose to go to the media before progressing a formal complaint to police.

I am all for a pile-on – after a guilty verdict by a court of law.

Just as the enablers of sexual misconduct were part of a rotten culture in the ’90s, a new class of enablers has emerged as part of the #MeToo movement.

They are the drivers of this new culture where legal advocates in a court of law are replaced with myriad self-appointed victim advocates in the media and in other institutions who rouse public opinion about a man’s guilt – and to heck with due process, the presumption of innocence and a fair trial. Months or years later, there may be a court process, but to what end? Before a charge is laid, let alone a criminal trial begins, the damage is done – quickly, publicly, irrevocably through trial by media, a career is destroyed, friends are lost, a family is crushed.

In these circumstances, what does an eventual acquittal by a court mean? The enablers of trial by media know this.

We can’t ignore the tensions between the media’s important role in helping to expose the abusive treatment of women and, at the same time, the media’s role in enabling this dangerous culture of trial by media. Dangerous because it transcends responsible reporting. Social media is an unregulated breeding ground for these public witch-hunts. As we saw with Scott Morrison’s injudicious apology to Higgins, and ACT chief prosecutor Shane Drumgold’s misguided press conference that he could win a second trial against Lehrmann, even senior leaders of powerful institutions – people who should know better – appear to have succumbed to the worst impulses of the #MeToo movement.

The pendulum has swung from a set of people who enabled men to abuse women to a new class of enablers who, to make amends for the past, and with the best of intentions to support women, are damaging fundamental values in a democratic society.

The same law firms and other professional bodies that turned a blind eye to sexual abuse decades ago now overreach by describing every complainant as a victim, leaving the presumption of innocence in a precarious state.

A spokesman for Britain’s Operation Hydrant, a police unit that will help the Metropolitan Police investigate the allegation against Brand, urged “any victim or survivor” to speak to police.

There are no victims yet, there are complainants. Taking an allegation seriously is very different to “believing all women”.

In this respect, the Sofronoff report into the Lehrmann matter missed a golden opportunity. Among the policy changes recommended in the final report, Walter Sofronoff KC did not suggest the word victim be replaced with a less loaded term in the Victims of Crime Commission legislation and to the title of the Victims of Crime Commissioner. That’s a shame.

Patently, to many people, including potential jurors, the presumption of innocence was placed in a precarious state when the Victims of Crime Commissioner accompanied Higgins into court, sat with her, and stood by her in front of cameras. Higgins was not a “victim”. She was and remains a complainant.

As we wait for our moral, political and media compass to settle somewhere more sensible, let’s not buy into Brand’s banal claim in recent days that there is a mainstream media conspiracy out to get him. “Is there another agenda at play?” he said in his statement this week. Some of his latest fans, including psychologist Jordan Peterson, hinted at dark forces. “Someone wants (Brand) destroyed,” Peterson tweeted.

Maybe it’s as simple as Brand’s past catching up with him. As journalist Rosie Taylor tweeted this week: “Anyone who thinks ‘the media’ plots Machiavellian global schemes should spend a week in a newsroom. Once you’ve witnessed news and features forgetting to talk to each other and Xmas taking us by surprise Every. Single. Year … you’ll realise we’re incapable of what you imagine.”

Brand has built a lucrative career by peddling conspiracies and battling bogeymen – from capitalism to cancel culture and Covid. Maybe he was the bogeyman all along. But he was aided and abetted by the media, first on the left when it was early Brand, then on the right when he transformed into anti-woke later Brand. Brand’s brand of sexual and political deviance turned audiences on.

That said, even a bogeyman who has made money from telling dick jokes deserves a fair trial.