How churches can make a comeback in today’s hostile culture

Christians are living in a perplexing environment, with state and culture turning against them. They can learn from the generous but uncompromising example of their forebears.

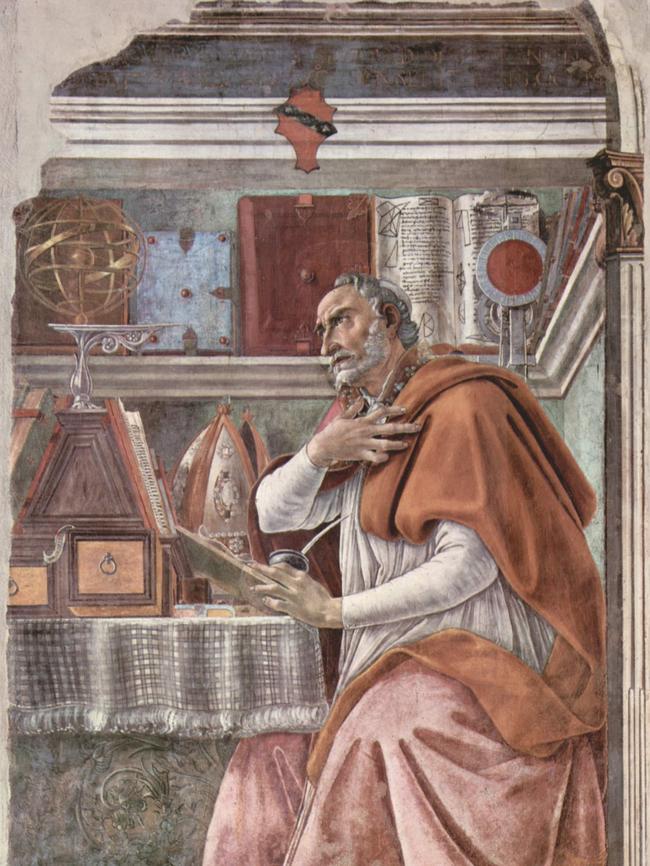

“You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” – St Augustine, Confessions

Easter is the triumph of the impossible and the unimaginable, the laughable story of the victory over death of the God/man Jesus 2000 years ago, which is the pivot of human history. It was a physical event and a metaphysical revolution. It upended the human condition and all of human history.

Easter is resurrection, but before resurrection comes death.

What does it have to do with us today?

Just now, in the debate about religious freedom, we confront a central question: will governments and government agencies make it impossible, or at least illegal, for Christians to practise Christianity within Christian institutions?

Can Christian schools preference teachers who support their ethos, ask its teachers not to campaign publicly against its teachings?

Can Christian hospitals continue the work they’ve undertaken for millennia of ministering to the sick and offering comfort to the afflicted without outraging the conscience of their medical practitioners?

Can Christian aged care homes work to support and comfort and glorify life, rather than to kill people?

If the answer to those questions is no, then governments are outlawing Christianity, or at least putting it on the level it sometimes occupied in the ancient Roman Empire.

Periodically, ancient Rome actively persecuted Christians, as the Chinese government does now. Quite often, it was willing to leave Christians mostly alone provided they made no public noise, and worshipped the emperor and acknowledged him as a god.

Christians couldn’t do this, and they got into a lot of trouble as a consequence.

Something similar is happening today, on a vastly less brutal scale. You can hold your Christian beliefs, the state increasingly rules, provided you do so in private, never utter in public things official “shame” ideology disapproves of, and acknowledge the majesty and infallibility of contemporary state doctrine on gender, identity and power.

The Chinese state is more explicit. Christian churches must feature portraits of Xi Jinping and acknowledge the Chinese Communist Party as the supreme arbiter of religious truth.

Christians today live in a perplexing environment, with the culture and the state turning against them. But they should be of good cheer. Christians historically have encountered circumstances a million times worse. Yet as Australian poet James McAuley wrote: “Suddenly as no one planned, behold the kingdom grow!”

No one had a worse public reputation than the first Christians. They’re a pretty good inspiration for today. Immediately after Jesus’s death, his followers initially were huddled in terror and confusion. After Easter, Jesus’s resurrection, as a matter of undeniable history, they went forth and successfully spread his message throughout the known world.

Today there are two billion Christians.

But there’s room for no complacency here. In Australia, as in the US, Covid was the latest blow to Christianity. According to a new study, The Great DeChurching, 40 million Americans across the past 25 years who used to go to church no longer do. As in Australia, a significant chunk stopped coming to church during Covid and haven’t come back.

Melbourne’s Catholic Archbishop, Peter Comensoli, in his recent Patrick Oration, observed that some two-thirds of Australians believe in God or a higher power, but fewer than 10 per cent actually practise religion.

Nor does the rise in the category of Spiritual But Not Religious offer much consolation, for “the generational movement of SBNR is not back towards the R, but further away from the S”.

Nonetheless, as Comensoli observes, many under-40s are not hostile to Christianity, they simply have no knowledge of God or Jesus. That makes them ripe for conversation, for the first movement to faith is always a gesture of welcome.

In frequently having no knowledge of Christian belief, transcendence and spirituality, today’s under-40s resemble in some ways the pagan peoples the early Christians lived among, to whom they spread the Christian message.

Societies like Australia are different from pagan societies in that they have been long softened by the ethical inheritance of Christianity, as Tom Holland demonstrates in Dominion. Not the least of the odd intellectual fashions of the past couple of hundred years has been the intermittent but persistent idealisation of ancient Greece and Rome. Yet the classical Greco-Roman world was just about as savage a society as humanity has known.

The savagery is evident even in the most elevated classical literature. Ovid’s Metamporphoses, which tells the mythical story of the world up until Julius Caesar is declared a god, contains much rape and murder. None is more savage than the story of Tereus, who rapes Philomena, the sister of his wife, Proce. Tereus then cuts Philomena’s tongue out so that she can tell no one what happened, and repeatedly rapes her again.

The most original and revolutionary people of the Greco-Roman world were the early Christians, who stood against the ethic and aesthetics of savagery.

They produced the first great sexual revolution, in which women, in their divine relationship to God, were equal to men. Celsus, a second century Greek philosopher and fierce critic of Christianity, mocked it as appealing only to “slaves, women and little children”.

Celsus had a point. The sociologist of ancient religion, Rodney Stark, estimates that in the second century, two-thirds of Christians were women. The earliest Christian church that archaeologists have found, at Megiddo in Israel, had a mosaic on its floor which honoured seven local Christians. Five were women.

In the Gospels, the first person to hear of, and then proclaim, Jesus was a woman, Mary. The first person she proclaimed Jesus to was a woman, her cousin, Elizabeth. At the cross at Jesus’s death only one man, John, was present, but there were half a dozen women. And then the risen Jesus shows himself first to a woman, Mary Magdalene, who proclaims the risen Christ to the apostles.

Classical Roman families valued sons far above daughters. They often left newborn daughters out to die of exposure. Even families liberal enough to keep a daughter seldom kept a second. Not only did Christian families keep and cherish their daughters, they rescued other families’ abandoned daughters and gave them life and love. They reconceived marriage as an institution of mutual love.

As soon as dedicated communities of religious devotion grew up, following on from the desert fathers of the church, mystics and others who wanted to devote their whole lives to prayer, similar communities of women flourished. Throughout Christian history, far more women than men have spent their lives wholly in religious devotion and charitable works.

The early Christians altogether are an enthralling group of human beings, even if you have no religious belief at all. They are one of the only cases in the classical world where we hear from ordinary rank and file people rather than exclusively nobility and elites. And without any notable power, they transformed the world.

Not only that, through their writings and records, and often enough their persecutions, they are remarkably accessible to moderns. At most you sometimes need to hunt out a good translation. It’s an imaginative failure of Hollywood that so few of their stories have come to the screen.

The Roman idea of religion was straightforward. You propitiated the gods with specific rituals and in exchange they gave you good fortune. All the gods were designed to further the interests of the Roman Empire. It’s fascinating to read Roman historians chart growing hostility to Christians as their communities grow. The great first century Roman historian, Tacitus, described Christianity as a “deadly superstition”. Pliny the Younger called it “depraved and excessive”.

Nijay Gutpa in Strange Religion recounts: “One of the accusations against Jews and Christians was that they were atheoi, godless” because they didn’t worship statues of Roman gods. Christians were subversive because they followed an executed criminal. Their sexual ethics were regarded as bizarre, then as now. Calling each other brother and sister suggested incest. They talked of eating the flesh of their God, incomprehensible to non-Christians, then as now. And while they didn’t look for trouble, there were things they wouldn’t compromise on, which made them stubbornly disobedient and difficult.

Also, they showed an unbecoming concern for the poor and for slaves. But when plagues came, they didn’t run away, but stayed and helped, helped their fellow believers but then helped anyone they could. Lots of them died as a result, but lots of them lived as a result as well. With all their daughters, their families were naturally happier than pagan families.

Also, unlike virtually all other religious groups, they didn’t belong to one tribe or territory. Their universalism was shocking to a civilisation which, then as now, regarded ethnic and racial identity as a central feature of the human condition.

Christian universalism, then and now, was distinctive: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male and female, but you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Without an overt ethic of universalism, humanity tends to retreat automatically into identity politics, ethnic chauvinism and tribalism, just as the Zeitgeist today is trying to impose a stultifying grid of identity politics on all of civic and even private life.

Christianity shockingly disregarded this completely.

Nonetheless, there is a sense in which Christianity was a colonial enterprise. From the very first, Christianity was a profound supernatural belief, an ethical imperative, a lived community and a deeply thought-out theology and philosophy.

It’s a gross anachronism to think early Christians lacked intellectual sophistication or depth, just as it’s a defamation to see the Jewish scriptures of the Old Testament as less than sublime.

A lot of the greatest early Christian writers, such as Augustine, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose of Milan and many others, were working bishops and pastors, fully busy looking after people, settling disputes, caring for the poor, teaching the gospels, and then at night wrote majestic masterpieces which shaped Christianity – and, incidentally, Western culture – ever after.

Three things strike me about them. So many of them had day jobs, yet wrote prolifically at astonishing depth. Second, their writing emerged from pastoral concerns; it addressed theological and human problems their own people were facing. There was no division between their spirituality and theology. And third, a surprisingly large number of them died for their faith, were martyred.

Three early Christian writers demand special attention: Augustine, Tertullian and Origen. Augustine was born in fourth century Thagaste and lived most of his life as bishop of Hippo, both in present-day Algeria. Tertullian lived in second century Carthage, in Tunisia. Origen was born in second century Alexandria, in Egypt.

More than any other early Christian thinkers, these three elucidated Christian theology and philosophy. Each got some things wrong, but they elaborated huge sections of biblical understanding, incorporating the trinity, the nature of God, the person of Christ, original sin, and much else.

Christianity began with Jewish Semitic people of the Middle East. It was authoritatively thought through and taught by three north African men of colour. So Christianity is indeed a child of a kind of spiritual and intellectual colonialism, first from the Middle East, then from Africa. We in the West are immense beneficiaries of this benign colonialism.

It’s a tragedy that none of these figures, and other early Christians like Irenaeus and Gregory of Nyssa, are taught anywhere but in specialist Christian studies. One interesting aspect of Gregory of Nyssa is that he learnt his theology from his sister, Macrina. One of his most important books, on the soul and resurrection, is fashioned as a dialogue with Marina, in which she is the teacher.

But Augustine is the most fabulously accessible and compelling of the early church teachers. He is sometimes called the last man of antiquity and the first man of medieval Christianity. Really he is more like the first modern. His Confessions are the first great psychological autobiography.

Find a good, modern translation and the Confessions are gripping. Get through the first few pages, which are very high-blown, and you fall into the compelling narrative of Augustine’s spiritual and personal development. For his first 32 years he was a pretty rugged sinner. A natural journalist, he produced brilliant headlines, such as the immortal “Lord make me pure, but not yet.” As a lyricist of piercing human insight, he stands with his fellow Christian, Bruce Springsteen.

Augustine rejected Christianity at first because he couldn’t accept the historical accuracy of the Old Testament. He dabbled in astrology and for a time was devoted to the cult of Manichaeism, which saw nature as an endless struggle between equal forces of good and evil. He was deeply intellectual and attracted to the neo-Platonists, who got to an anaemic version of God purely through reason.

But in Milan he fell under the influence of Ambrose who taught him to read some Old Testament books, Genesis particularly, as allegory and metaphor. He picked up a Bible and struck the words: “Put on the Lord, Jesus Christ.”

Augustine experienced mysticism, but his life was mostly concerned with looking after the people of Hippo. Christian villages needed protection by Roman soldiers, which led him to develop the just war theory, which informs international law today. But then Augustine witnessed the collapse of the Roman Empire, which led to his great work, City of God, which teaches Christians they have no abiding city on earth.

The early Christians were by no means perfect. They had their quarrels, problems, failures and episodes of wickedness. But they were overwhelmingly good. They didn’t lead lives of seraphic serenity. But they never lost faith. They are hard to emulate because their courage was so striking.

Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Kanishka Raffel tells Inquirer: “It is the supernatural elements in Christianity, and a life formed in the light of them, which is attractive to people. Most early Christians were disempowered people who found to their surprise that God was interested in them. The idea that God knew them from the inside gave them great power.”

Lots of things early Christians did in their worship and community were common sense and applicable today – the emphasis on shared meals, on music, on welcome and community, and on serving the poor. But they never shied away from, and were utterly transformed by, the sheer truthful, wild, inspiring weirdness of Christianity.

Christ is risen.

“Everybody’s got a hungry heart.” – Bruce Springsteen