Never more have we needed Easter’s divine message of love

It doesn’t matter if we believe the story of the resurrection … it believes in us.

“In spite of that, we call this Friday good,” T.S. Eliot wrote. Why the qualification from the great poet who was also a fervent believer? Because the first and terrible part of Easter is the Crucifixion, the death of the Son of Man who is inseparably the Son of God. It’s a tragic story. Think of how Jesus prays before he is apprehended and the way it has always been known as the Agony in the Garden. “If this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done.” Think of the great cry from the cross of apparent despair: Eloi, eloi, lama, sabachthani, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” His own godhead has left him bereft and his mortality has become a terrible thing even though in death as in life he knows He is the one the prophet Isaiah spoke of. But it is a weird and terrible story we are born into, the Passion of Christ.

And it is ours, however far from it we try to get. It is not a simple matter of what we think we believe, this story runs deep in the culture that defines us. And, by the grace of whatever’s good, there is the transcendent glory that comes when the figure in white walks luminous from the tomb, there is the Resurrection. Orthodox Christians on their Easter Sunday say to whoever they meet, “Christ is risen” and the reply comes “He is risen indeed” (“Christos Anesti,” “Alithos Anesti”).

But let’s go back to the Passion, the story that led to yesterday’s hot cross buns and fish and chips. Judas comes and betrays Him with a kiss. Jesus is led to Caiaphas, the high priest, the man who maintains the terrible belief (if carried to its logical extremity) that it is expedient that one man should die for the sake of the nation.

Just at the moment the Middle East is wracked with the horror of everything that has followed in the wake of October 7 and the Hamas abductions and killings and the thousands of Palestinians who continue to be killed and starve in Gaza while sincere kids chant “from the river to the sea” in apparent denial of Israel’s right to exist as a nation while others execrate Jews as if nothing had been learned from the mass collaboration with the Nazis.

Jesus comes before the High Priest who says to him: “I adjure thee by the living God that thou tell us whether thou be the Christ, the Son of God.”

Jesus saith unto him, “Thou hast said it. I tell you that hereafter shall ye see the Son of Man sitting on the right hand of power and coming in the clouds of heaven.”

The High Priest knows what this means. It is the claim to be the embodiment of the Most High. He has blasphemed. And so they make their way to Pilate seeking his death.

Meanwhile, Judas kills himself in a fit of despair at what he’s done and Peter fulfils Jesus’s prophecy that before the cock crows he will betray his master three times. He goes off and we’re told “wept bitterly”.

And so the drama accelerates as He is brought before Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator. The governor’s wife sends a message to him and says, “Have nothing to do with that just man: for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of him.” Ultimately we will see Pilate wash his hands and declare – guiltily and in disbelief – “I am innocent of the blood of this just person.” Pilate is a fascinating figure, laconic and brilliant. “Art thou the king of the Jews?” And when Jesus asks a question he replies with patrician disdain, “Am I a Jew?” And then there is the moment when Pilate seems to blunder headlong into the perception of the Good. Jesus answered, “My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world then would my servants fight.”

Pilate therefore said unto him, “Art thou a king then?” Jesus answered, “Thou sayest that I am a king. To this end I was born and for this cause came I into the world that I should bear witness unto the truth. Everyone that is of the truth heareth my voice.”

Pilate saith unto him, “What is truth?”

Francis Bacon in Reformation England referred to “jesting” Pilate because he was a man who “would not stay for an answer”. We have Pilate’s impotent tribute to Jesus when he has the sign put on top of the cross “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews” and the Chief Priests say he claimed to be king of the Jews and Pilate replies, “What I have written I have written”: in the Latin of Saint Jerome’s Vulgate, “quod scripsi scripsi”. He is a hell of a literary model, Pilate, but what does he amount to as a human being?

There are all sorts of touches that are convincing, however much we may think, oh yes, myths of dying gods were all the rage at this moment in Greco-Roman history. Remember the moment when one of the thieves who has been crucified along with Jesus says to him, “Lord remember me when you come into your Kingdom” and Jesus replied, “I tell you that this night you shall be with me in paradise.”

Are we conned into swallowing the whole mimetic thesis of Erich Auerbach about the style of the Gospels as so much wishful thinking? That this is just the kind of story that would be concocted at that moment in history. It’s worth pondering the power of something like prayer, heaven help us. And what kind of wishful thinking produces a dying god myth of such scarifying power?

Good Friday is the day when the mass, the eucharist is not celebrated because that is a commemoration of the thing which is thought of as actually happening on Good Friday and people instead go to Stations of the Cross in the morning – that great critic Susan Sontag once exclaimed of the ignorance of the young “they don’t even know the Stations of the Cross” – or to the service at three in the afternoon which is centred on the reading or singing in Gregorian or plainchant of John’s Passion. Of course, this can be done at a high and mighty level if we approach it through Bach’s Saint John Passion with its extraordinary transfiguration of the Lutheran religious elements with tremendous vigour and veracity which some people prefer to the monumental magnificence of the Saint Matthew Passion but each of these oratorios which summon up universes of human experience justify Wagner’s description of Bach as “the most stupendous miracle in all music”.

The Saint John Passion is shorter than the Saint Matthew Passion which is sometimes said to be Bach’s greatest work. It has a graphic power and captures a sense of the ominous cruelty of the crowd who are mercilessly depicted through contrapuntal choral work. The state of the art version of both the Passions are those of John Eliot Gardiner who has a great clarity and cleanliness of articulation but there is a 1971 version of the Johannespassion conducted by Benjamin Britten with the Wandsworth School Boys Choir which is in a very adept English translation slightly adjusting traditional biblical English – translating “Herr”, for instance, as “Sire”. The soloists included Peter Pears as the Evangelist, Gwynne Howell as Jesus, as well as John Shirley-Quirk and Heather Harper.

There is also – while we’re pondering the artistic revelations that accompany our sense of the truth of Easter – the extraordinary Klemperer version of the Saint Matthew Passion, which is out of date according to any contemporary fashion but has an unearthly power with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Jesus, Peter Pears (again) as the Evangelist and the lavish talents of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Christa Ludwig. This sounds for all the world like the greatness of the voice of Truth. The lavishness of the vocal technique is matched – uncannily – by the religious intensity of the vision conveyed. This version – which is a bit like a marriage of Beethoven and Bach – has a tragic power but it also by some miracle conveys a sense of wonder and exultation.

And that is central to Easter because this most solemn moment in the Christian calendar ends in triumph with the Resurrection. In the 19th century, when religious belief was visceral in the intensity of its literalism, all sorts of people, including that supreme master of dramatic fiction Dostoevski, were aghast when they saw the Crucifixion of Matthias Grunewald because the corpse of Christ had been so brutally executed that the work is like the instantiation of the death of God. This is part of the Isenheim altarpiece which mercifully includes a Resurrection and is in many panels. It is a form of Gothic art and has an overwhelming power.

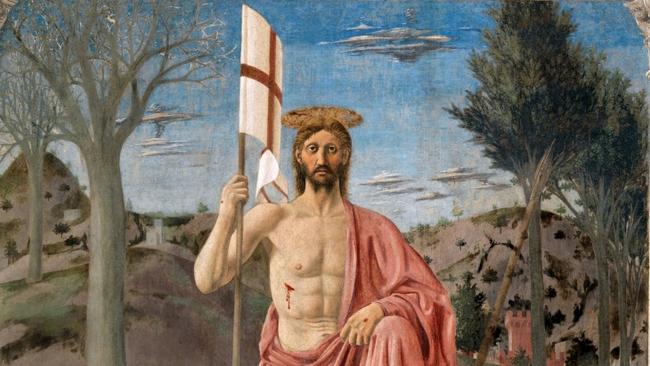

The diametric opposite to this nightmare image of human pain and all its excruciating implications is in Piero della Francesca’s 1450 Resurrection of Christ which happens to use geometric structures with dazzling brilliance. It famously has a quality that has been dubbed “sublimity”.

That marvellous art critic the late Peter Schjeldahl said it was the quality that might once have driven someone into a monastery but could now make them become an art critic. The bizarre thing about the Piero della Francesca Resurrection is that it makes someone suspend disbelief. Obviously we do this all the time with great forms of art. When Dante writes “L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle” (Love which moves the sun and other stars) we believe in what is being said because of the power of the verbal music, just as when Francesca says “La bocca mi bacio tutto tremante” (He kissed my mouth all trembling) we kindle with the apprehension of how they got together. In the case of Piero della Francesca, we are looking at an image that embodies the resurrected Christ.

This is a painting that defies us not to believe in the reality of the Son of Man come back from the dead. It’s a quality, of course, that you get throughout great art.

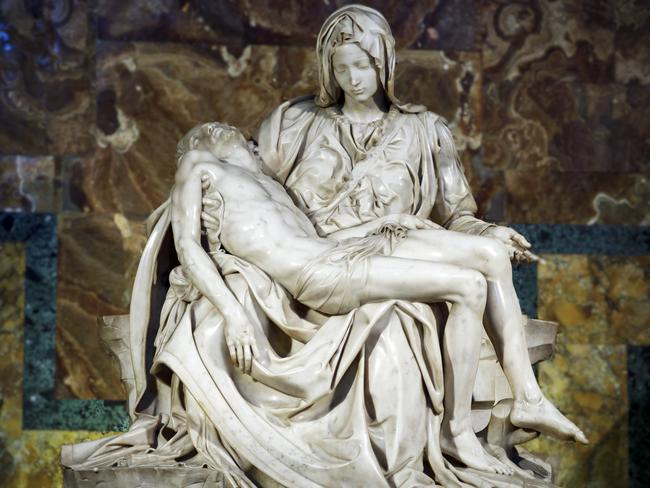

You can take Michelangelo’s Pieta and the way the intense beauty of the grieving Madonna has such an extraordinary symmetry with her dead son.

Or you can take Titan’s wonderful and gorgeous image of Mary Magdalene meeting Jesus after he’s risen. It’s a beautiful encounter when he’s come out of the tomb.

At first she doesn’t recognise him and he just says, “Mary” and she does. She says “Rabboni”, which means master.

What Jesus says to her is “touch me not”, or as Saint Jerome has it “Noli me tangere” which is what Titan called his painting and Jesus’s separateness, his unearthly buoyancy, is part of the greatness of the image. Mary Magdalene in the Jesus Christ Superstar song said she didn’t know how to love him (“I’ve had so many men before/ in many different ways / He’s just one more”) but Christ said: “Much is forgiven her because she hath loved much.”

Nothing about this greatest story ever told contradicts the story of the carpenter’s son, peasant-born, influenced by the Dead Sea scrolls, the Essene stuff embraced by the Baptist.

Of course, you can have your dying god and your immemorial cult of spring. But think about that masterpiece of a film, Pasolini’s The Gospel of Saint Matthew. It’s like a documentary of genius about a true story.

It doesn’t matter whether you believe in the Easter story or not, it believes in you. The grandeur of everything that hedges it about is compatible with that ethical credo we back a long way from but do we really disbelieve it: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole soul and thy whole heart and thy whole mind and thou shalt love they neighbour as thy self.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout