Dominic Perrottet and the future of Australia’s fractured federation

Scott Morrison must restore unity and the nation’s power balance.

Scott Morrison presides at this crossroads. At stake is his prime ministership but also the authority of his office. The test is whether the Labor premiers, having weakened Morrison in 2021, can become frontline allies of Anthony Albanese to ensure Morrison’s election defeat next year.

The issue in 2021 has been Morrison versus the premiers. If that remains the issue in 2022, then Morrison loses the election. But if the premiers are eclipsed by the reopening of the economy and the election is normalised – Morrison versus Albanese – then Morrison has a serious re-election prospect.

Covid has turned the premiers into giant-killers, yet this may be transitory. The year 2022 will answer the two critical questions: whether Australia is witnessing an institutionalised power shift to the states; and, if not, whether Morrison has the political personality to restore authority to the office of the prime minister.

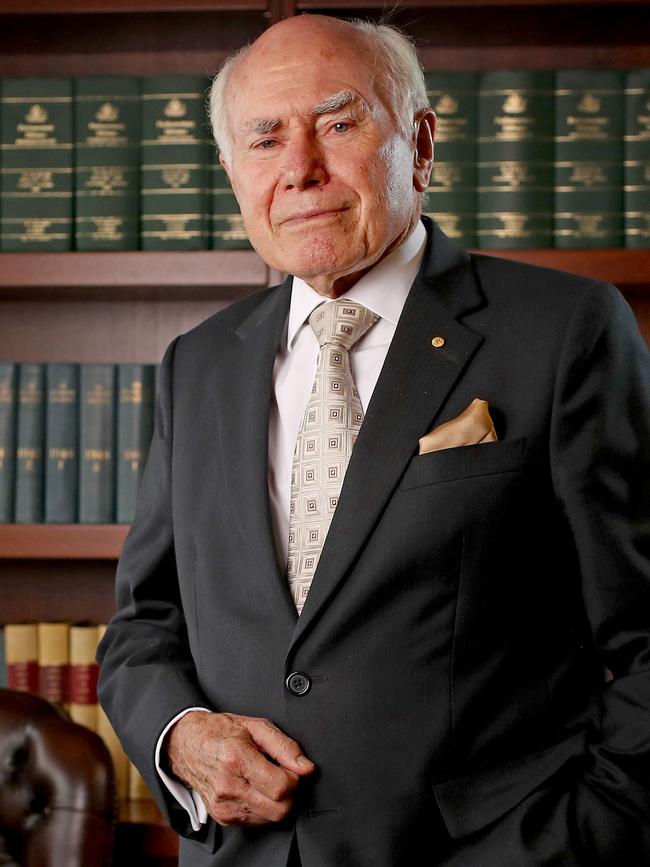

The John Howard/Bob Carr school, in effect, says “there’s no revolution, stay calm”. Howard tells Inquirer: “This idea that the Australian federation faces a crisis or the federation is breaking down is bunkum. I believe we are not seeing a fundamental change. We should be mature enough to realise these are powers the states have always had but never had to use before Covid. They have lain dormant for decades. Now whether they’ve been wisely used is a separate matter.”

Carr tells Inquirer: “This Covid situation is absolutely a one-off. The Australian federation is completely loaded towards central power, more so than other models such as Canada and Germany. The current situation with the premiers is an aberration.”

Yet the political power of the premiers has been potent. How does Morrison manage this in an election? A member of Morrison’s ministry tells Inquirer: “It depends upon the question. If we ask West Australians which team do you want: McGowan/Morrison or McGowan/Albanese, that leads to an obvious answer. If we ask Queensslanders whether their preferred team is Palaszczuk/Morrison or Palaszczuk/Albanese, that also leads to an obvious answer.”

Howard, a Liberal leader subject to attack at the 1987 election from then Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, is sceptical about the election clout of the premiers. “I think a lot will depend on the assessment by the Labor premiers about how likely it is that federal Labor will win. They will go through the motions. What happens to Daniel Andrews? His support is starting to waver a bit. I don’t think Mark McGowan is going to die on the altar of Albanese’s future.”

The election of former NSW treasurer Dominic Perrottet as Premier has a singular meaning – Perrottet is a conviction politician. He believes in opening up the economy. His first decisions show his determination to accelerate the NSW transition out of lockdown from next Monday with the 70 per cent double vaccination level having been reached.

This will accentuate the divisions among the premiers. Perrottet’s actions dramatically increase the stakes in the fractured federation. He rejects the Covid ritual of premiers parading their health officials beside them extolling the lockdown mode. Perrottet wants to return life to normal.

Morrison is riding with Perrottet. His entire election strategy depends upon a successful opening-up in NSW. Perrottet is carrying Morrison’s fortunes before him. Have no doubt, across the nation progressive politicians, premiers, media and health experts will wait and launch a withering counter-attack if NSW comes under too great a strain and struggles to cope. This is a watershed moment in Australia’s power struggle.

“Australians are beginning to get their lives back,” Morrison said this week, signalling his 2022 election strategy. He wants to see states opening up successfully, the economy returning as the central issue, Australia close to the world’s highest vaccination rates, and a major economic statement or budget leading directly to the autumn 2022 poll.

Yet the split within the nation is deep – between state and federal, state and state, conservative and progressive. Interviews conducted by Inquirer point to a nation confused and divided about the legacy from Covid-19; whether it signals a permanent change in power within Australia or merely a more complex political battle involving all federal and state leaders.

Long-time federalist and former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University Greg Craven says the Australian commonwealth is at risk. “The Australian states are ripping this federation apart,” Craven tells Inquirer. “It is true they have their grievances. Canberra never respected their constitutional rights and treated them as mendicant irritations. But what a revenge.

“Already, it realistically is impossible to imagine Western Australia or Queensland voluntarily implementing Morrison’s 70 to 80 per cent national vaccination plan. Ironically, for someone who has supported state rights all his life I’m deeply worried about where we are. Australia will not fail like Afghanistan in blood and tears. It will collapse like the civilised state it is – in a welter of self-interest, disputation and mistrust.

“Australians have a common fantasy about the states, which is that there’re not much different and we’re all just Australians. But that is simply not true – there are huge differences between the states. My worry is that the states, having tasted a degree of freedom they have not had since World War I, are not going to give it up easily. Are these premiers going to return to their former setting? Well, that gives rise to another question: Why would they?

“The situation is worse than saying the states are in command. The situation is out of command. We are adrift on a sea of circumstances and chance.”

Craven says Morrison needs to find “his inner John Curtin” to save the federation. He warns that history shows federations have failed to grasp threats to their integrity until it was too late. He says the 1930s saw the underestimation of the secessionist movement in WA until the state actually voted to secede (by a huge 66-34 per cent margin.)

An alternative view came from Sydney University law professor Anne Twomey, a long-time student of federation. “There will be people walking around today complaining about the states who would be dead if it wasn’t for their state governments,” she tells Inquirer. “That’s just a reality. We know the death toll would have been higher if the states hadn’t closed their borders.

“What is significant is that the states have been leading,” Twomey says. “They have been leading in Covid and in areas like climate change. The states are acting more assertively than in previous times.”

She says the federation in the pandemic was operating the way it was intended. She defends the states, rejects any notion of a federation crisis, and says a more assertive future role for the states will depend upon leaders, personalities and policies.

“I don’t think it is ever realistic to say national cabinet should mean one policy and one unanimous agreement that applies across the country,” Twomey says. “Each premier is responsible to their own parliament and to their own people. It’s understandable they have disagreements. It is important in a federal system for each state to apply general agreements in a way that meets the needs of their people. If WA doesn’t have Covid, then its policy settings are going to be different from a state like NSW where you have had high levels of Covid.”

Morrison is now on a quest to rebuild his authority as PM after the premiers controlled every aspect of the public health fight against Covid – from lockdowns to schools, masks and commerce. The premiers will dominate any debate about public health; the prime minister will dominate any debate about national economic recovery. Repeated analogies between Covid and wartime are false. During Covid, the states have controlled the response; in wartime, it is the national government that dominates.

While Morrison has been under constant assault from the populist right for not defying the premiers and overriding their lockdowns, any such confrontation would have destroyed his government. Initially, Morrison wanted to challenge the states in the High Court on closed borders but then backed off, realising it was a doomed political project.

Asked about demands for Morrison to have tackled the premiers front-on, Howard says: “I just think that was unrealistic. I think Morrison has handled the thing well. He has understood what power you have, and what power you don’t have. Because people have never witnessed this before, there’s a bit of a knee-jerk reaction that the states are acting beyond their power and the federal government should rein them. Well, it can’t rein them in. The Morrison government cannot dictate whether people wear masks. It can’t even do that in Canberra.”

Morrison predicts that NSW will “stay safely open”, despite the concerns of the Australian Medical Association and the still ominous Friday case figures at 646. Perrottet’s assumption is that ongoing high vaccination levels will do the job, with NSW first jabs about to hit 90 per cent. Morrison’s tactic is to market NSW as a “sign of hope” to the rest of Australia.

He encourages all states to move towards reopening, signalling that when that happens Australia will be united again. The kudos for Morrison in this event would be significant – a restored federation, a reunited country.

“I want to see Australians all reunited once again,” Morrison said. “I have no doubt all premiers and chief ministers around the country want to see that as well.”

Here is his ideal election framing. But the reality is different. The premiers won’t roll over for Morrison. They will cut him nothing beyond their self-interest. Indeed, they may sabotage the federal election campaign. McGowan has said WA won’t reopen its border until 2022, and even floated extending the closure until April. Tasmanian Liberal Premier Peter Gutwein has said Tasmania won’t open its borders until 90 per cent vaccination is reached. As for Annastacia Palaszczuk, who could possibly guess where she will end up?

Australia faces the potential of a federal campaign with some state borders still closed. How does that work? Morrison wants to avoid political warfare with the premiers but is now engaged in a calculated clawback of his authority as PM. He announced this week international travel reopening from November, with NSW leading the way. Fully vaccinated NSW residents will be flying to London and Los Angeles before Christmas while residents of other states remain locked-in subjects of their premiers.

Josh Frydenberg has announced the elimination of federal emergency support funds at 80 per cent vaccination. That is, the states are being forced to pay their own way. The Treasurer at a press conference put the curse on Dan Andrews, saying: “Melbourne, tragically and sadly, has gone from being the most liveable city in the world to the most locked-down city in the world.”

Andrews cannot escape; this branding will be his legacy. Consider his record compared to NSW: far more deaths, far more days in lockdowns, more daily cases, a lower fully vaccinated rate – 56 versus NSW’s 70 per cent – and a much slower opening-up. To this point, Victoria is a singular loser on every count.

Progressives need to beware. The lesson, so far, is tough lockdowns, authorised by health officials and backed by the public, have made many premiers into heroes. But the politics is now shifting rapidly. This is not necessarily how the story of Australia’s pandemic ends. Killing businesses, damaging jobs, shutting schools, and creating mental health epidemics – in measures pursued with a relentless ideological bent – may yet be seen as a misplaced faith in repressive measures to confront the virus.

The final chapter is coming. Much depends upon the success or otherwise of the opening-up now spearheaded by Perrottet. If he succeeds, that success will guarantee a reassessment of which policies were best for Australia.

The former Victorian Liberal premier Jeff Kennett warns the resurgence of state government populist powers will diminish Australia unless it is curbed. “The premiers have postponed our ability to manage the virus,” Kennett tells Inquirer. “At the moment, we are isolated. Look at the overseas coverage Australia is getting. The world is changing very quickly. Unless Australia can find a common purpose, then we will finish in a far weaker position.

“The only way Australia can survive and prosper independently in the long-term is by being socially and economically strong. We need to recognise that our national future depends on everybody kicking for Team Australia. It doesn’t mean states can’t have their own identity, but our leaders are not working with each other. That’s what been missing for the past two years.

“I don’t think these changes in the federation will endure. That’s because they can’t endure. This country is not eight separate islands. We are one island. I’m a realist but also an optimist. I think there will come a moment of reckoning when leaders are forced to look at the bigger picture.”

But that task will defy some leaders. When the toll of rhetorical ignominy is weighted, few examples will match Palaszczuk’s “Queensland’s hospitals are for Queenslanders” as the ultimate symbol of blind, disreputable, selfish populism.

There are two broad scenarios for Australia’s post-pandemic future. The first is a country more obsessed with its internal differences, more divided, more introverted, less international, more populist in outlook but more tentative in substance – a diminished federation with a body politic damaged by the scale of trauma. The second is more optimistic: a revival of competitive federalism, a recognition that states must take a greater responsibility for themselves, operate as bolder agents, be distinctive but within a national framework with the arrival of a reformist Perrottet, leading the biggest state, being a pointer to the future.

Australia’s federation is at the crossroads. The nation faces a choice: either the established order of national government dominance will be resurrected in 2022, or the country will sink into a Covid legacy of parochial state populism with damaging consequences.