Since October 7, scores of letters and petitions have circulated and been signed by thousands of journalists in the Anglosphere that not only called on governments to end their support for Israel – journalists urging a change in government policy – but urged journalists to side with the Palestinians, preference their voices and implicitly silence the voices of Zionists and Israel defenders. Defenders of a genocidal state.

There was hardly a mention of what happened on October 7 inside Israel in these letters and petitions from journalists and, if it was mentioned in passing, it was contextualised and implicitly justified.

Neither did any of these letters call out and condemn the rape and torture of women and girls by the Hamas terrorists and as a result the increasing and horrific evidence of these crimes against humanity have been downplayed by women’s organisations including UN Women and by most of the media.

This ignoring in the main or at best underplaying the crimes against women and girls by Hamas terrorists was activist journalism at its most powerful.

In the main, media executives – editors and news directors – were surprised by these petitions and letters, which they knew compromised their journalism and compromised all the journalistic values they constantly told their readers and their television and radio audiences that they passionately adhered to.

But the fact is that many media companies’ – newspapers and their digital platforms and television and radio news services – had long ago given up on defending and enforcing the values on which their journalism was ostensibly based – fairness, factual accuracy and, crucially, reporting that is free of agenda pushing and activism.

It is just that the Hamas massacres and the Israeli war against Hamas have shown in a very dramatic way how journalism has changed in recent times, how many journalists have come to see their role as warriors for social justice, for the anti-colonial struggle, the anti-racism struggle, for the oppressed against the oppressors.

We have been here before, in the middle of a crisis that starkly illustrated the fact the old ethical principles of journalism were being discarded by many journalists and, crucially, perhaps the world’s best known and most venerable liberal-leaning newspaper, The New York Times.

And where the Times goes, so tend to go many left-liberal newspapers outside the US.

In June 2020, at the height of the Covid pandemic, riots and looting and mass demonstrations were held in cities across the US after the death of George Floyd, who died after a white policeman had knelt on his neck for nine minutes. The riots and the looting and the mass Black Lives Matter demonstrations and the demands by activists to defund the police meant that in some cities demonstrators and rioters had transformed inner-city areas into no-go zones for police.

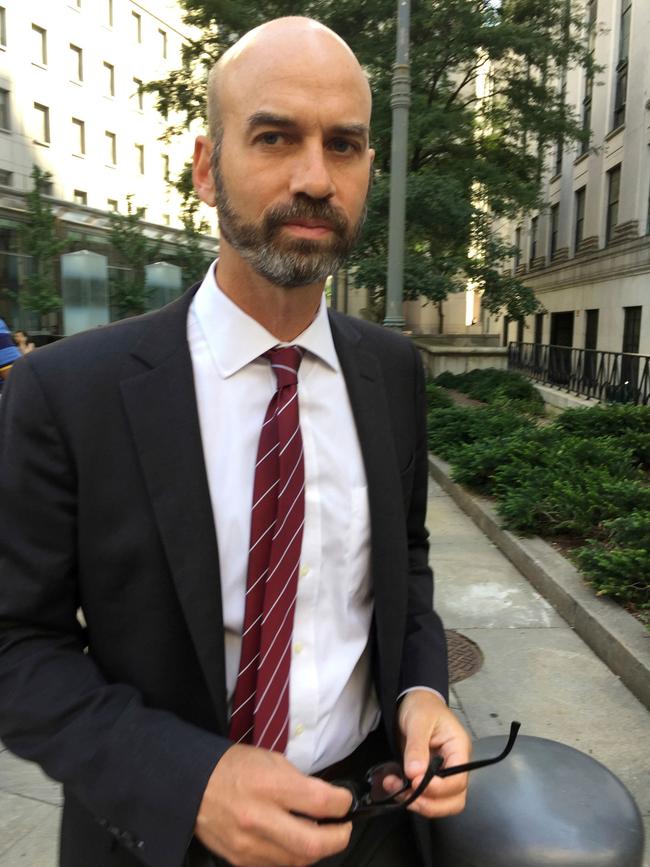

At The New York Times, in the first week of June, with areas of some American cities out of control, governed more or less by demonstrators and some rioters, James Bennet, the editor of the editorial page of the paper, approved the publication of an opinion piece by Tom Cotton, a leading Republican senator and a supporter, a lukewarm one it must be said, of Donald Trump.

It is worth re-reading the Cotton piece, which calls for an intervention by the US Army. This sort of intervention has happened before and it is not unconstitutional―to quell the rioting and looting in American cities. It is, in my view, a run-of-the-mill piece, not brilliantly written but not bad either. It is not a rabidly Trumpian call for the army to be deployed against peaceful demonstrators, which is how many Times journalists―and journalists beyond the Times―saw it.

Certainly the publisher of the Times, AG Sulzberger, did not see it that way: Sulzberger publicly and privately supported the editor he had appointed in 2016, the editor he had lured back to the paper from The Atlantic where Bennet had been the editor for a decade. It was, the publisher said, a perfectly legitimate piece for the Times.

But a few days later, after mass staff protests, after demands from some journalists that Bennet be sacked because he had made some journalists on the Times feel “unsafe” by publishing the Cotton opinion piece, Sulzberger called Bennet and, according to Bennet, Sulzberger was furious, and he demanded that Bennet resign. The op-ed, he said, did not meet the standards set by the Times. Bennet resigned, having at first said the publisher would have to sack him.

He changed his mind and resigned because he did not want to damage the institution, the paper that he still loved, the place where he had learnt his journalism, where he started in 1991 as an intern, where he had worked for 15 years, where he had been a White House correspondent and the paper’s Jerusalem correspondent, and where he had built his reputation as one of the country’s finest reporters.

Now, three years later, Bennet, who is a columnist for The Economist, has written a 16,000-word essay about his resignation and what it meant, but the essay is about much more than that. It is an examination of the way The New York Times went from being an admittedly liberal newspaper to an illiberal one, a newspaper where the liberal elites talk to themselves. A newspaper whose readership is overwhelmingly progressive and woke, whose readers read the Times to have their ideological positions affirmed. They do not read the paper for reporting and commentary that challenges these ideological “truths”.

And his forced resignation was a milestone along the road to this illiberalism at the Times – an illiberalism, while perhaps not as pronounced, that has to some extent infected media companies in Australia, Canada, Britain and New Zealand, though not nearly as much in liberal democratic Europe.

Bennet’s essay feels like it was the past three years in the writing. It is deeply detailed about his time at the Times and his relationship with Sulzberger and editors. He describes how it felt when he came back to The New York Times in 2016 after a decade at The Atlantic magazine and found the newspaper he had grown up on unrecognisable, well along the road to the illiberalism that eventually would force him out.

Bennet describes how the election of Trump in 2016 had a profound impact on journalism, especially progressive journalists in the US and even in Australia and Canada, how for them Trump’s victory was inexplicable and shocking.

It remained inexplicable and shocking to these journalists for the four years of the Trump presidency. Instead of doing what journalists should do and go out and find out how it was that Trump was elected, who voted for him and why, many journalists saw it as their mission to call out Trump for his lies, his fascist tendencies, his crimes, his danger to American democracy. In other words, to ensure he does not win the 2020 election and, even better, that he is impeached and forced to resign.

Bennet, in the eyes of these journalists, had betrayed that journalistic mission by publishing an op-ed by a Trump-supporting senator that was urging Trump to call out the army against the Black Lives Matter protesters. How much more traitorous could you get at the Times?

Perhaps the part of Bennet’s essay that is most affecting for an old journalist is his deep reflection on journalism, on what it means to be a journalist, perhaps the best such reflection I have read for a long time. Bennet was and remains a journalist committed to the institutions of journalism – in his case, a commitment to The New York Times and the values that he absorbed and was committed to upholding during his time at the paper.

Yes, it was a liberal newspaper, but it was committed to fair and accurate reporting and the publication on its opinion page of a wide range of commentary. He describes his journalistic education at the Times, which had nothing to do with any university course. It started in the city section of the paper where a chain-smoking old editor once took him for a walk and told him if he didn’t improve in certain ways he would never be given a permanent position on the paper.

He describes how other editors educated him, how he learnt to be a better reporter by being assigned stories that he initially thought were mind-numbingly boring but that turned out to be memorable, even life-changing, like a series he did on being old in New York.

Bennet writes that this sort of mentoring and training on the job is rare now at the Times – and I believe it is increasingly rare in most media companies. At the Times, when the paper felt under threat from new media such as the Huffington Post and an array of other start-ups, many of which have now disappeared, it went out and hired people from these new online outfits who had little experience of journalism and no on-the-job training and, crucially, no commitment to and no knowledge of―the institution that was employing them.

But they were tech savvy and they understood how social media worked, and many of them were contemptuous of old journalists such as Bennet. I think some of this has happened in some Australian media companies. Institutional loyalty is disappearing. There was a time journalists felt attached to the newspaper where they worked and were proud of that attachment. That was true to a certain extent for journalists who worked for the ABC or for commercial news broadcasting.

Journalists are becoming brands, hypersensitive to their social media following, always working to cultivate a greater following because the more followers you have, the better the journalist you are and the less you are beholden to the paper or network for which you work.

Many of the thousands of journalists who in the past two months have signed letters and petitions demanding a right to be activists for the cause of the Palestinians, demanding that governments change their policies towards genocidal Israel, consider themselves to be brands in no way obligated to consider the effect of their letter and petition signing on the institutions for which they work.

Many wouldn’t know whether the newspaper or broadcaster where they work has a code of conduct to which they are bound when they are employed. Many would never have had the sort of journalistic education that Bennet describes in his essay.

Bennet is pessimistic about the Times, about whether it can go back to being the paper it was when he fell in love with the place because of its values – despite its liberal bias―and because of the mentorship he had from editors who were great educators and because it was at the Times that he fell in love with being a reporter.

At this troubled time, there are signs of hope. The New York Times a few weeks ago forced two journalists who had signed group letters that were pro-Palestinian to resign. They had refused to make a commitment to sign no further group letters of any kind. Signing such letters was against the paper’s code of conduct.

In Australia a couple of weeks later, the editors of the Nine newspapers told their staff that those journalists who had signed letters and petitions would be barred from covering any element of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, including its effect on Australia’s Jewish and Muslim communities.

Even The Guardian has an updated code that states that its journalists must not sign group letters and petitions because by doing so they would be seen to be compromising The Guardian’s journalism.

There is hope but, at the same time, it is hard to read the Bennet essay and not feel some measure of despair.

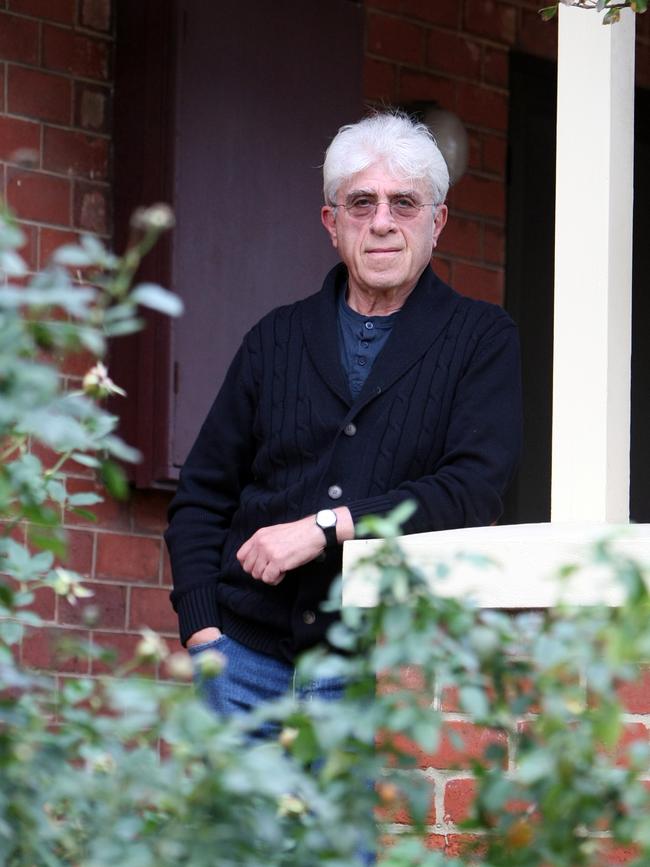

Michael Gawenda is a former editor of The Age.

Within days of the Hamas massacres in the south of Israel on October 7 and before the subsequent Israeli war against Hamas in Gaza with its horrific civilian death toll, thousands of journalists in the US, Britain, Canada and Australia signed letters and petitions that called for journalists to provide “context” for the Hamas massacres, and that context was that Israel was a racist colonialist state.