Coronavirus fear spreads as China’s New Year exodus begins

As Chinese New Year looms, Beijing confirms a new strain of coronavirus can be spread from human to human.

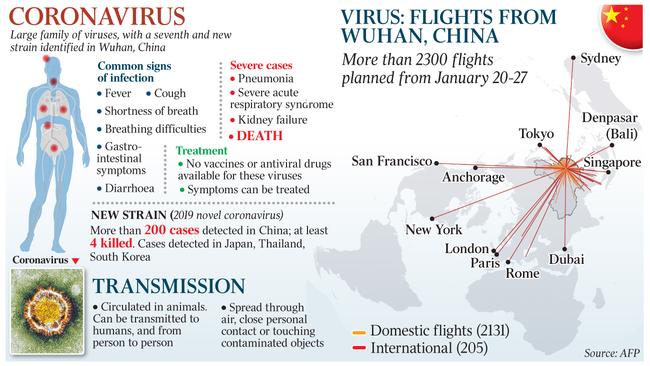

Just as the world’s largest annual migration of people has begun this week in China, and among ethnic Chinese populations globally, health authorities there have confirmed a new and potentially deadly strain of the coronavirus is now spreading from human to human.

The timing could not be worse.

Hundreds of millions of people are taking boats, planes, trains and automobiles back to their families to celebrate Chinese New Year, fuelling fears of a major outbreak.

At least 224 people in China are now confirmed to have contracted the virus, which is believed to have originated at a seafood and livestock market in the central city of Wuhan, and has already killed four people there.

Nine other cases are considered critical.

The number of infected patients has more than tripled in recent days, thanks in part to the recent availability of a diagnostic test for the disease.

But now the disease also has spread across China and to Thailand, Japan and South Korea, and Australian authorities confirmed on Tuesday they were testing a Brisbane man for the new coronavirus strain after he returned from visiting family in Wuhan with a respiratory illness.

Scientists at the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College London estimate the real number of infections could be higher than 1700 based on traffic through Wuhan’s main airport since the first case was detected last month.

With infection rates rising rapidly, World Health Organisation officials will decide on Wednesday whether to declare the outbreak “a public health emergency of international concern”.

The designation is reserved only for the gravest epidemics that threaten to cross borders and require an internationally co-ordinated response, such as the 2014 West Africa Ebola epidemic, the ongoing Ebola outbreak in Congo and the 2016 Zika virus in the Americas.

An emergency declaration almost certainly would affect the Olympic women’s soccer qualifying tournament scheduled to be held in Wuhan early next month, at which Australia’s Matildas are to take part.

In South Korea, Japan, the US and across Southeast Asia, authorities are implementing body temperature checks at airport gates and aboard planes to prevent the spread of a virus that triggers a type of pneumonia among carriers and is raising fears of another deadly epidemic similar to the 2002-03 severe acute respiratory syndrome.

South Korea confirmed and isolated its first case on Monday after a 35-year-old woman arrived from Wuhan displaying symptoms.

Flight screening

Australian Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy says biosecurity officials will begin screening passengers arriving on the three weekly flights to Sydney from Wuhan starting on Thursday, though not with body temperature scanners, which he says proved ineffective during the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

“The important thing to remember is with border screening you cannot absolutely prevent the spread of disease into the country,” Murphy says.

While common symptoms of the strain are high fever, coughing, sore throat and breathlessness, the week-long incubation period for the disease means infected travellers may well show no symptoms on arrival.

“So it’s about identifying those with a high risk and making sure those who have a high risk know about it and know how to get medical attention,” Murphy adds.

“There’s no way of preventing this getting into the country if this becomes bigger. We need to respond to it as we always do.”

Authorities also will analyse the hundreds of direct and indirect flights weekly from China to Australia to determine which pose the highest risk and should also be monitored.

Trying to contain the virus in the face of the single biggest people movement on the planet presents a public health nightmare — and never more so than as many millions more middle-class Chinese choose to spend their holidays abroad.

In 2017, the top 10 overseas destinations for Chinese New Year tourists were Thailand, Japan, US, Singapore, Australia, Malaysia, South Korea, Indonesia, The Philippines and Vietnam. Australia now receives more than a million Chinese tourists a year.

While Wuhan is a major transit hub and China’s seventh most populous city, monitoring only incoming flights from there to Australia would be futile given China has confirmed patients in other parts of the country contracted the virus without having visited that city.

Zhong Nanshan, a renowned scientist at China’s National Health Commission who helped expose the scale of the 2002 SARS outbreak, says two patients in southern Guangdong province were infected by family members who visited Wuhan.

New cases also have been confirmed in Beijing and Shanghai. More are suspected in four provinces and regions in the east, south and southwest of the country, and 14 medical staff have contracted the virus from one carrier.

“Right now is the time when we should increase alert,” Zhong says.

“The key to controlling the spread of the disease now is about preventing the emergence of a super-spreader,” he adds, referring to infected patients who could quickly help spread the virus, especially among medical workers.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has urged officials to “release outbreak information in a timely manner and deepen international co-operation”.

“The recent outbreak of novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan and other places must be taken seriously,” Xi says.

“Party committees, governments and relevant departments at all levels should put people’s lives and health first.”

Lessons of SARS

Asia learned hard lessons from the 2002-03 SARS epidemic, another strain of the coronavirus that also originated in China and comes from the same class of pathogens as the latest disease.

The SARS outbreak killed 774 people worldwide — though mostly in China and Hong Kong — infected thousands more and sparked serious disruption to global travel and trade.

Takeshi Kasai, the WHO regional director for the Western Pacific, says that in the years since then many countries have established emergency operations centres, rapid response teams, introduced field epidemiology training programs and surveillance systems for early identification and monitoring.

Yet rapid urbanisation and dramatic increases in the movement of people and goods are making it harder than ever to contain the spread of new and dangerous viruses.

The impact of climate change — which has expanded the geographic reach of epidemic-prone diseases — also means outbreaks of diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome and yellow fever are reaching places they could not only a few years ago.

To deal with the increasing threat, Kasai says, all countries need to modernise their disease surveillance systems, act faster and in a more co-ordinated way to prevent the spread of disease. “No one can undertake this journey alone — not a single country, nor a single organisation. We must work together, reaching across sectors, to prepare for the next pandemic,” the senior WHO official wrote in a piece published on the organisation’s website and in the Nikkei Asian Review last week.

“We must test and update response plans time and again. We must continue to strengthen the systems required to implement responses. And we must keep up momentum to continue improving health security.”

In 2002, it took China a full three months to announce its first confirmed SARS case.

This time, Beijing has moved far more quickly to share genetic sequencing data on the coronavirus with other countries. It has closed down the seafood market, suspected to be ground zero for the new strain.

Experts from Taiwan and Hong Kong also have been allowed to visit Wuhan.

Slow response

But some critics say China still has been too slow to control the spread of infection, pointing out that it was not until January 14 that Wuhan authorities installed thermal imaging scanners at the international airport, bus and train stations to detect abnormal body temperatures.

Taiwan’s health officials began on-board temperature inspections late last month, while body temperature screening began at Hong Kong International Airport and Singapore’s Changi International Airport on January 3.

Even the bullishly pro-Beijing Global Times has sounded a stern warning about the dangers of covering up a new epidemic.

“All relevant information must be notified to the public, and there must be no concealment,” it said in an editorial this week.

“Concealment would be a serious blow to the government’s credibility and might trigger greater social panic. In the early moments of SARS, there was concealment in China. This must not be repeated.”

The newest coronavirus brings to seven the number of strains now communicable between humans, though not all are deadly.

At least four are known to cause symptoms barely more serious than those associated with the common cold. The other two — SARS and MERS — are known killers.

More than 850 people died during the MERS outbreak in 2012.

China’s National Health Commission is still insisting the current outbreak is “preventable and controllable”.

“However, the source of the new type of coronavirus has not been found, we do not fully understand how the virus is transmitted, and changes in the virus still need to be closely monitored,” the commission said on Monday.

Along with public health authorities across Asia, it is advising its citizens to wash their hands frequently, not to eat undercooked or raw meat, to avoid contact with live animals, or with people showing symptoms of illness, and to wear a mask if they have a cough or runny nose.

Arnaud Fontanet, head of the department of epidemiology at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, agrees the new coronavirus strain appears to be weaker in its current form than SARS, but warns it still could mutate into a more virulent strain.

“We don’t have evidence that says this virus is going to mutate, but that’s what happened with SARS,” he says.

“The virus has only been circulating a short time, so it’s too early to say.”

Additional reporting: Agencies

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout