Coronavirus: Britons living in a state of high anxiety

I always knew the British public was conservative and considered, but I never expected them to be so frightened.

A caveat here — she and I are among the 11 per cent.

Most people in Britain, 89 per cent if you believe the polls, fiercely support the lockdown and want to hide in a cupboard until the holy grail of a vaccine is available. I am sure they have taped a poster of the government’s mantra Stay at Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives to the back of the toilet door.

I’ve lived in London for more than 10 years and I always knew the British public is conservative and considered. But I never expected Britons to be so frightened, so willing to throw away their civil liberties. As a short-term health policy, social isolation is an effective measure, but coronavirus is not short term. It is likely to be with us for generations.

It’s true that vaccine development and global collaboration have never been more rapid, and work has begun on multiple candidates, including one from the University of Oxford being tested with animals by Australia’s CSIRO. And although a time frame of 12 to 18 months is often cited, that is optimistic. There are simply no guarantees of success, and if a safe, effective vaccine is achievable it may be years away. Think of attempts to find a cure for malaria, HIV-AIDS, the common cold.

More realistic is the hope being pinned to therapies that can obviate the virus impacts.

Yet the British government, floundering while prime minister Boris Johnson recovers from his intensive care experience, is seriously considering locking up anyone over 70 — for their own good, mind — for a couple of years. This is all premised on the potentially low odds (less than 10 per cent, one expert says) that any one of the four human vaccine trials around the world will prove effective, especially for the less robust immune systems of the elderly.

It is as if politicians have created their imaginary timetable, that a cure of impeccable safety and effectiveness, scaled up to treat 7.3 billion people on the planet, will be delivered on time next year.

Grey rebellion?

So, as well as panicking the population, this government is considering ordering a generation of men and women who survived the Depression and the Blitz and took part in Dunkirk to end their days without the presence of loved ones and the joy of cuddling grandchildren. Surely these fiercely independent over-70s can weigh up the health risks themselves?

A word has evolved here: catastro-fetishists, those self-flagellating do-gooders peeking over the modern fence of social media to shout down and embarrass anyone who is looking beyond the immediate health impacts of the virus. Their view is not only to extend the lockdown but also to tighten it. The attitude of “cancel everything” is as common as the couples walking in the local park, clad in masks and plastic gloves, despite there being no evidence the virus is passed on when walking past someone in the street, yet lots of evidence it is communicated indoors and sharing of airconditioning systems.

No one wants this virus, but it is very much here in Britain and not likely to be quashed, unlike the very different situation in Australia and New Zealand. Scientists predict more than 10 per cent of the British population, 6.7 million people, have had it. In London, where commuters ram on to packed Tube services, the rate is tipped to be much higher. Most aged under 75 have recovered, even those few who have had terrifying two-week illnesses.

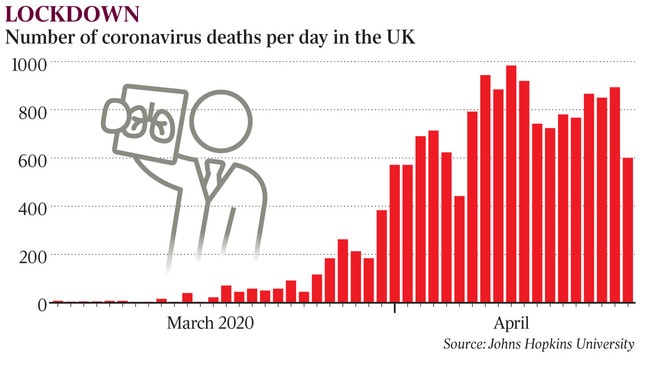

To date, more than 16,000 people have died of coronavirus across the UK, most in London in the past four weeks. It is worth pointing out that without coronavirus, it is usual for 10,000 people to die each week in Britain.

Future inquiries will be scathing of the lax British response and the backdown from the herd immunity plan that has meandered into no plan at all. Last weekend, The Sunday Times reported that Johnson had missed five meetings of the government’s emergency Cobra committee and the paper claimed he had delayed a coronavirus response for 38 days.

Home affairs

In February through to March, Johnson had successfully delivered Brexit and was preoccupied with delicate family concerns of finalising his divorce, announcing his engagement to partner Carrie Symonds and also a new baby to the rest of his estranged family, while the government was downplaying the human-to-human transmission of the virus across Chinese borders. (The UK border is still open, it has never been shut).

As a result, Britain was caught short in personal protective equipment for frontline staff, there was not enough testing and the government had to backtrack on its initial herd immunity plan — in place in Sweden — and then switch to try to suppress the virus.

Now the government is terrified of the headlines of 900 daily deaths, including elderly care home patients with comorbidities, the obese and those with heart conditions. Men are dying at twice the rate of women. At the moment coronavirus is listed as a factor in one in five mortalities.

Just where does the country go from here? To try to get the transmission rates as low as possible and deaths in the tens, rather than the hundreds, will take long and damaging self-isolation. Then it will demand a follow-up program of hundreds of thousands of tests a day, repeatedly, when the country can barely muster more than 15,000 a day at the moment.

The initial lockdown was always presented as a way to save the NHS, and so far the health services have coped more than admirably. The cabinet is thus torn: let the virus spread while the NHS can cope or lock down the country for many more months to come. The reality will probably be a slow release from lockdown next month, although on Sunday Education Secretary Gavin Williamson couldn’t even say that schools would reopen come May 11, the first Monday after last Thursday’s haphazard three-week extension of lockdown.

However, what is starting to concentrate minds is the skyrocketing social and health costs elsewhere. With empty wards and highly experienced doctors left twiddling their thumbs, as requisitioned private hospitals and the newly built Nightingale hospitals haven’t been needed, medical experts are alarmed at the ongoing health impacts on non-COVID-19 patients and the backlog of surgeries that will take years to clear.

Says Richard Sullivan, professor of cancer and global health at King’s College London: “The number of deaths due to the disruption of cancer services is likely to outweigh the number of deaths from coronavirus over the next five years. Screening services have stopped, which means we’ll miss our chance to catch many cancers.”

I benefited from the hesitancy of Johnson’s cabinet to introduce social distancing, having a hospital operation on a suspected melanoma on the last day the cancer surgery ward was open in the middle of last month. What about all those who were scheduled to follow me? Some distraught women with breast cancer diagnoses have been told their treatment will start “in the late summer”.

Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty repeatedly has stressed to the public that the NHS is still open for medical emergencies, fearful that people suffering strokes, heart attacks and sepsis are delaying visits to hospitals, with deadly results.

Mental health risk

Yet British hospitals have thousands of spare intensive care beds available. Four times the normal number of acute beds are unoccupied as non-COVID-19 patients are discharged early. New mothers are being sent home within hours of giving birth. Surveys on mental health across the land are frightening. Half of the country is suffering “high levels of anxiety” and four in five adults say they are very worried or somewhat worried about the effect that the coronavirus is having on their life right now.

Public Health England is so concerned about spikes in suicides, it is collecting data on self-harm rates in Manchester, Oxford and Derby, and asking for intelligence from the helpline Samaritans to assess where the risks are likely to occur. The clapping and banging of saucepans every Thursday evening in a show of solidarity with medical staff has echoes of a Blitz-like spirit, but for many it simply underscores the ongoing physical barriers and the inability to share a pint down the pub or to socialise with friends. Then there is the economic impact, which by default will have significant consequences for poverty levels. Each day Britain is in lockdown costs the economy £2.6bn ($5.1bn).

Despite this morass of anxiety, cabinet members seem inexplicably wary of making big decisions while Johnson recuperates. Last Thursday Scotland’s First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, bounced the rest of the UK into a three-week extension — worth £60bn or so — because the cabinet couldn’t make up its mind, so she deferred to advice from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. Six weeks ago no one knew these men and women existed, yet now this SAGE committee, a secretive group of unelected “experts”, wields unprecedented power.

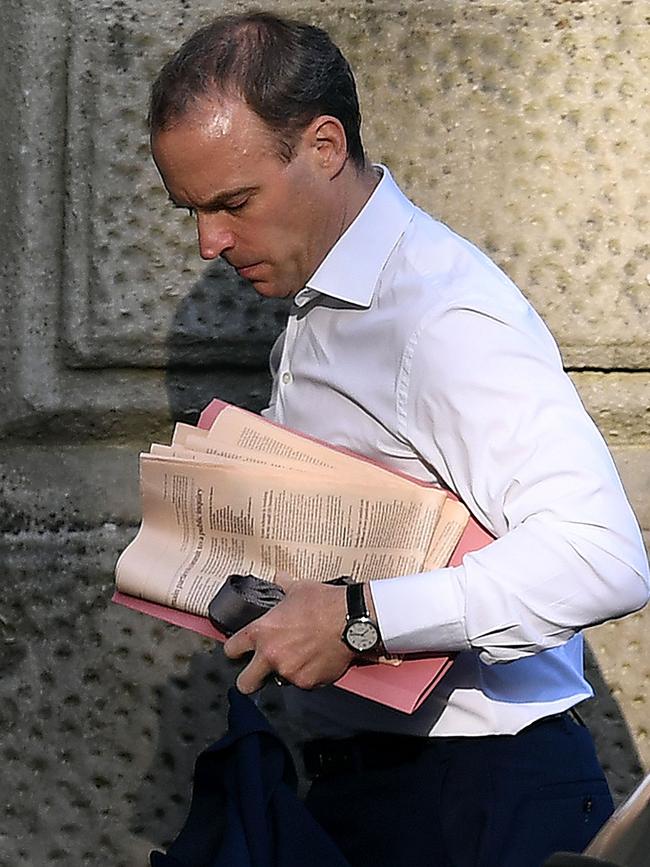

Foreign Secretary and Johnson deputy Dominic Raab can only mutter “we will make the right decision at the right time”, effectively making no decision, and prefacing each statement with the slogan “based on the scientific advice”.

But the identity of most members of this SAGE committee is top secret and no notes are kept of their meetings. Are their decisions unanimous? No one knows. What is the background of their expertise? Again a mystery. The public has to take on faith that what SAGE wants is the best overall for the country. Yet what is so desperately needed is leadership and a transparent plan, for the coronavirus “cure” of self-isolation is arguably proving worse than the disease on many fronts, not just health.

Thursday’s announcement of an extended lockdown was illustrative for what wasn’t said. There was no long-term plan, no advice for the elderly and vulnerable who are suffering terribly with loneliness, no consideration of mental health impacts, little acknowledgment of associated deaths from a reoriented NHS that is focusing almost exclusively on coronavirus, and no suggestion that schools may be reopened, let alone addressing chaos in manufacturing and supply chains.

Incredibly, Raab insists the country will be economically better off by being shut down for longer, without providing any data to back up such a sweeping statement. His argument goes that if there is a second wave of infections and the country has to lock down again, it will be more financially damaging than prolonging the current near zero output.

Raab said: “I want to be clear about this. The advice from SAGE is that relaxing any of the measures currently in place would risk damage to both public health and our economy.”

Meanwhile the government’s economic experts say the country’s gross domestic product will plummet by 35 per cent and unemployment will skyrocket to 10 per cent if the lockdown persists.

There has been increasing scrutiny and community concern about indecision at the highest levels amid growing anger that members of the public are being treated as fools. The government risks losing trust. The only publicly known SAGE member is chairman Sir Patrick Vallance, the country’s chief scientist. He says the R value, or transmission rate, is below 1, meaning one person infects less than one other on average. Other NHS experts concur and say the country has passed the peak.

Raab has stressed that any future “lockdown adjustment” must not be allowed to overwhelm the NHS, which hasn’t been overwhelmed so far during this pandemic. But without allowing some form of normal life to resume, how is that risk to be assessed?

Finally, in the front window of a small London shop — a one-person operation making leadlights — was a sign of rebellion. Not the rainbow pictures eulogising the National Heath Service but a printed message: End the Lockdown Now. I could have hugged the shop owner, a woman in her 70s, but I am not allowed.