Clive James: A mind for beauty and truth

The brilliance of Clive James is his Aussie honesty.

When the news of Clive James’s death came it was almost a footnote because for so many years we had been aware of the fact he was dying and then, when it finally happened, this expected and foreordained thing was somehow a strange surprise.

He had announced he had leukaemia back in 2011 but in the ensuing years he had done extraordinary things such as translating the whole of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, arguably the greatest work of art of medieval civilisation and certainly of Italian literature, and with typical Clive-like confidence he had put the footnotes into the versified text because he thought that these days Dante needed them.

So who and what was James? He was the greatest man of letters of that generation –– in fact they were a handful –– of Australian expatriates who had an enormous impact on the Britain they took to like a destiny and a challenge.

There was Barry Humphries, that supreme comedian who is probably the greatest performer (and writes his own comedy too) this country has produced. There was Humphries’s fellow Melburnian, Germaine Greer, who like James went from English literature –– Shakespeare and Cambridge in her case –– to embrace a world and change it with all those enunciations and modifications of feminism that came like a bomb with The Female Eunuch.

And there was Robert Hughes, art critic extraordinaire and writer of that masterpiece about the convicts, The Fatal Shore, James’s fellow Sydneysider though from an immeasurably posher background. Hughes was the greatest critic in any medium Australia has produced and James said of him once, in relation to his adopted New York: “I suppose he needed something that big at his feet.”

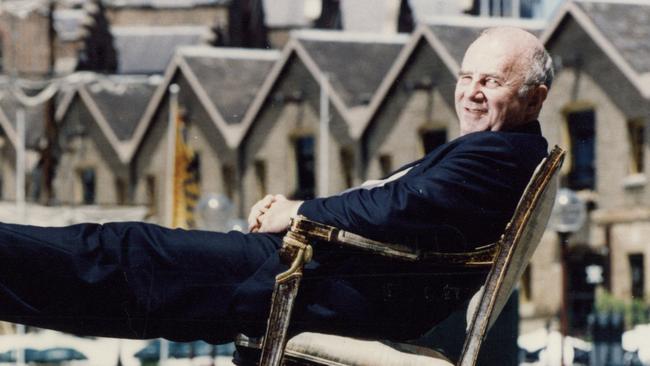

What James needed was the traditional worldliness and sophistication of London, partly one suspects because it allowed the perfect setting by way of contrast, for his wry Australianness.

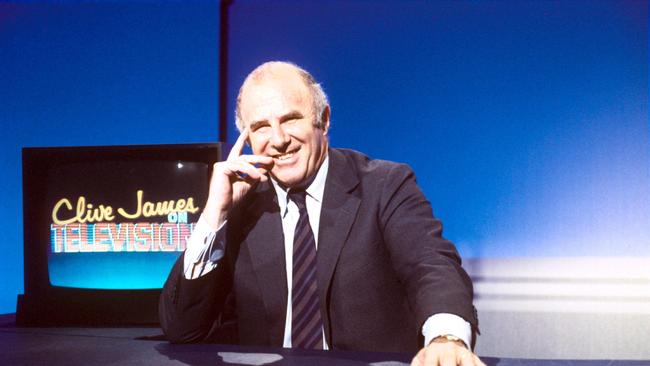

Of that group of Australian expats, James was the most versatile. He was one of the greatest essayists we have tossed up, he was as great a critic of television as Kenneth Tynan was of theatre and he also did television –– free-to-air mass market British TV with a strong element of self-mocking comedy as well as interviews in Saturday Night Clive and Sunday Night Clive.

But also The Late Clive James, that vertiginously highbrow show in which you might see Barbara Amiel, the wife of newspaper magnate Conrad Black, say: “The real problem with journalism is self-censorship.” And hear James reply with absolute speed and dazzling insolence: “Have you been censoring yourself lately, Barbara?” Or you might hear George Steiner attacking the shade of TS Eliot (for supposed anti-Semitism) with a European vehemence while Eliot’s defender, Christopher Ricks, sat in what looked like stiff embarrassment.

James was an absolutely fearless interviewer. He interviewed Roman Polanski, unafraid of all the dark and troubled waters of his sexual past and crimes. Even more defiantly he interviewed Katharine Hepburn, and the silence she kept after he dared to ask her about her great lover and co-star Spencer Tracy must have been one of the longest silences ever observed in the history of TV.

And still James got extraordinary things out of the great actress as she revealed detail after detail of her past in that impossibly aristocratic Yankee accent.

It’s hard not to talk about James in relation to the people he encountered and homed in on because his interest in them was so intense though the gaze beneath that balding unlovely brow was always at some level unenthralled because celebrity to him was a fascination, not a fixation.

And that’s probably true even of what he said about Princess Diana, with whom he used to have lunch and who terrified him by sitting at window seats in restaurants (which made James, always fearless in his confessions of cowardice, imagine they would be shot at by some murderous passing maniac).

He was an extraordinary figure, though, because he was interested in everything and he had the remarkable quality of being able to turn journalism, the higher journalism but still, into a form of literature because he made its impact indelible.

One of the greatest essays I know –– comparable in its way to anything Dr Johnson or Gore Vidal, among polar opposites –– is the essay he wrote for the New Yorker 20-odd years ago talking about Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners, the book that argued the German people were always totally complicit with the Holocaust. James began with one of those sabre thrusts that instantly go down in history.

“In the end,” he said, “Hitler would have killed everyone.” Then he went on, piece by piece, item by item, to exemplify what had happened to every Lutheran pastor, every turbulent priest who attacked the Nazi regime.

He said, too, how with someone such as Claus von Stauffenberg, the aristocratic soldier who attempted to assassinate Hitler, he would have grown up with a background where anti-Semitism was in the curtains of his upper-class German family home.

The whole essay is an exercise in what can be described only as impassioned restraint and it’s all the more remarkable because James was notable for his freedom of mind and the way he could wing it on every subject under the sun.

This quality was written all over the later pieces he wrote for The Times Literary Supplement, after his retirement from TV, in which he was a kind of cultural smorgasboarder par excellence.

He was always a dazzling and dashing critic even if you could baulk at the overweening self-confidence. His friend poet Peter Porter (whom James would not, I suspect, have considered himself the equal of, any more than he would have considered himself the equal of Les Murray, for James the greatest of Australian poets) always maintained the University of Sydney produced a kind of cocksure brilliance in some of its alumni compared to which Oxford and Cambridge paled into hesitant modesty.

If you want the purely brash James, try this on the greatest German language poet of the 20th century: “Rilke used to say that no poet could mind going to jail, since he would at least have time to explore the treasure house of his memory. In many respects Rilke was a prick.”

This is not James at his very best, even if he’s right about the prison nonsense. It is, of course, James at his most “Australian” and it’s typical that he nails with absolute precision the reason Australians make such good critics on the rare occasions that they do. After all, except for Humphries who is a satirist, the famous expats were all critics of a kind.

“Popular culture,” James said, “was my observation point. I had a natural affinity to it. Nothing was more natural to me than to say what I thought. It was a big advantage to come from a country where saying what you think is something you do all the time.”

This is brilliant because it captures the way in which James’s sense of how his Australianness allowed him to be a colonial bull in a decorous English china shop was profoundly liberating to him.

It’s one reason, too, he was so good at sending himself up. After all, no one has written a greater ode to literary resentment than this: “The book of my enemy has been remaindered / And I am pleased. / In vast quantities it has been remaindered / … In the kind of bookshop where remaindering occurs.” That’s the facetious side of James and in its more or less idle way it’s liable to live forever.

There is another side to James that is altogether more modest and ultimately more formidable.

Here is a bit of the elegy to his father, who died in a plane crash at the end of World War II: “I look up to the sky, / down to the sea, / And hope to see them, / while I still draw breath, / The way you saw your photograph of me / The very day you flew to your death. / Back at the gate, I turn to face the hill, / Your headstone lost again among the rest. / I have no time to waste, much less to kill / My life is yours; my curse, to be so blessed.”

That is James at his finest as a poet and it is at the furthest possible remove from the glorious jokey pseudo-poems such as Bring Me the Sweat of Gabriella Sabatini or Last Night the Sea Dreamt It was Greta Scacchi, to which Martin Amis, so I was told by Julian Barnes, replied simply: “It did not.”

It was that formidable wonderfully charming man Ian Hamilton, poet and biographer of Robert Lowell, who published 10,000 words of James, early on in the TLS, writing about one of the greatest American critics, Edmund Wilson. And I remember his friend, that dour Scot Karl Miller, the greatest literary editor of his generation, saying to me with apparent grimness: “Clive James talks to me as if I were a very beautiful woman.”

He talked to a lot of people like that including (needless to say) beautiful women. His marriage to Prue Shaw, the Italian literature don, ended in 2012 after Leanne Edelsten declared she had had a long affair –– eight years in fact –– with James. He admitted characteristically to having behaved badly and being a “bad husband”.

At one level James will live for his great one-liners, such as saying Arnold Schwarzenegger looked like “a brown condom stuffed with walnuts” which is, to use an old Australianism, constantly uttered in his childhood, very lairy –– which is to say brashly and ostentatiously vulgar.

It’s not actually as good as his quieter but also often cited quip describing George Orwell: “To write like him, you need a life like his, but times have changed and he changed them.”

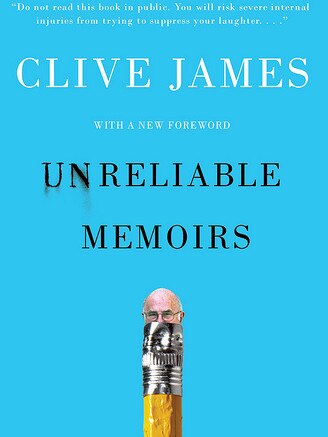

But the greatest James wasn’t really in the one-liners, neat though they could be. The man who moved like a comet through Honi Soit, who lived with film director Bruce Beresford and swooned at the magnificence of the young Hughes and a few years later, after he went to England and became distracted from the PhD he was supposed to be doing on Shelley and was invited to join the Footlights Club –– that seedbed of so many great comedians (Peter Cook, John Cleese, you name them) –– probably wrote his greatest work in the first volume of his memoirs, Unreliable Memoirs (1980), in which he depicts the borderline between fiction and nonfiction, his childhood. It is a magnificent account of his boyhood in Kogarah and, above all, a sunlit and plangent portrait of his beloved widowed mother who gave him all and more than all.

In typical James fashion it comes with an epigraph from Homer’s Illiad (on Andromache). This first volume of memoir, delineating the remembrance of things that have nothing to do with starry careers –– though James’s fame was the precondition of its publication –– is in fact his masterpiece.

Masterliness was written all over him. He was probably the most canny of those high and mighty refugees from Menzies’ Australia and harboured for a long time a horror of Australian parochialism: he said it dragged you down if you had to mix and mingle with cultural mediocrity. At the end, though, the light of that Australian childhood, when he was too sick to come back, glowed like the eye of God to him. “My mind basks in the light I never left behind.”

He will live on as a brilliant critic, a brilliant TV host popular and highbrow, and as a fine poet. But most of all, in its first volume, as a memoirist of genius. It’s the Kogarah stuff they would be mad not to read in 100 years.