Climate change and our renewable energy future is a crazy brave world, says Alan Finkel

‘Forests of wind farms carpeting hills and cliffs from sea to sky.’ Alan Finkel paints a vision of the net-zero future some would find alarming. But he’s clear: it must be done.

Former chief scientist Alan Finkel was at a dinner party soon after the 2022 federal election when a fellow guest, in a “triumphal tone”, expressed her confidence that the new political and climate-focused era would usher in a speedy transition to net zero. The optimistic guest could not see the mighty challenges ahead, but Finkel does.

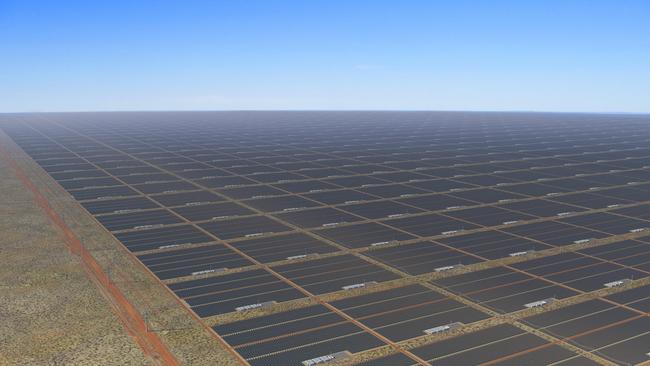

And he paints a vision of the future that would stop most dinner party chit-chat dead in its tracks: “Think forests of wind farms carpeting hills and cliffs from sea to sky. Think endless arrays of solar panels disappearing like a mirage into the desert.” Mining on a vast scale to supply the minerals for batteries and solar panels; giant factories to build the parts for wind turbines; endless kilometres of transmission lines to connect it all to consumers, entire workforces retrained; financing at unprecedented levels. Converting an energy system nourished by fossil fuels to one based on wind and solar is a task of barely imaginable proportions, he says, and there can be no papering over that fact.

“The sheer scale of the task, I pointed out to (dinner guest) Kathleen, is why we’ve barely made a dent in reducing global emissions despite three decades of effort and concern … We’ve shaved off 4 per cent in the last 30 years. In the next 30 we need to shave off 83 per cent.”

Kathleen’s triumph soon dissolved to despair, Finkel writes in the opening to his new book, Powering Up: Unleashing the Clean Energy Supply Chain.

That sense of dashed hope may well be the emotion felt by others reading the first few pages and wondering how the world will accelerate towards what he calls the most profound economic change to civilisation of all time.

Finkel is an electrical engineer and neuroscientist. As chief scientist from 2016 to 2020 he led the review of Australia’s electricity market, the development of the national hydrogen strategy and the national low-emissions technology road map. He has been an adviser to industry and governments on both sides of politics. “And I’ve spent over a decade thinking about the climate problem,” he says.

Now he has released his blueprint for the clean energy transition, a plan that steps through the supply chain, from raw materials and mining to homes and consumers, examining the positives and the problems.

Sitting in his Melbourne office one late autumn afternoon on a video link, Finkel is, in fact, cautiously upbeat – yes, there are bumpy roads ahead, but he has great faith in human ingenuity. Many obstacles thrown up during this transition phase can and must be overcome to mitigate the harmful effects of climate change. And look at the benefits.

With our abundant minerals and renewable energy, Finkel sees incredible opportunities for Australia – even those who think the threat of climate change is overstated should be able to see the economic possibilities, he urges.

“There’s every reason we should be a very significant exporter and participant in not just the clean energy revolution but clean product revolution, whether it’s steel or fertiliser or jet fuel. But other countries are moving hard and fast, too, so we have to get things right.”

How Australia meets its renewable targets

Even so, Finkel is no more than “hopeful … confident we’ve got a chance” to meet our 43 per cent emissions reduction and 82 per cent renewables targets by 2030 – goals he describes as rational and appropriate.

“We have to do it,” he insists. “The reality is that there is a necessity to decarbonise the energy system. We have to get off oil, coal and gas. The future requires that. But it is a serious challenge … anyone who thinks it is easy is not appreciating the complexities of what’s being done here.”

In Finkel’s world, problems require solutions. That’s the engineer in him. And so he won’t spend time in our interview ruminating on politics (although in his book he observes that previous governments included “too many reactionaries who objected to change”) or quibbling about the Albanese government’s recent approval of a new coalmine.

“The reality is that Australia not exporting coal or gas won’t make any difference at all to the use of oil, coal or gas in other countries,” he says. Similarly, he says while coal-fired plants have no future, shutting them before firmed solar and wind generation plants are built risks extended electricity blackouts. “That would not just be a disaster for modern life; it risks rescinding the social licence for moving as fast as we can to net zero,” he writes.

When it comes to climate change, he says, we must listen to the scientists – but also to the engineers who operate the energy networks and to the economists.

“So, when scientists make the argument that we must shut down coal-fired generation immediately because the science says so, this ambition needs to be reconciled with the reality that in Australia nearly 60 per cent of our electricity generation comes from coal,” he says. “Shutting it down immediately is not an option.”

The answer, he says, is to rapidly make renewable technologies so competitive they render fossil fuels obsolete. “The way to remove interest in using oil, coal and gas is by providing zero-emissions electricity that is cheaper, cleaner and more convenient.’’

Natural gas-fired electricity, he says, will have a role of last resort in supporting solar and wind long after coal-fired generation ceases. And in decades to come, he predicts, the cost of hydrogen production and storage will have fallen to a level that will make it possible to use stored hydrogen instead of gas. (Hydrogen, he predicts, will play a big part in Australia’s export future and in producing decarbonised products such as iron.)

But the transition won’t come cheap. Finkel notes that the International Energy Agency has estimated that costs will increase to about $US4 trillion (almost $6 trillion) a year by 2030, for a total of about $US100 trillion by 2050. “These are large numbers indeed,” he concedes. But he sees this cost as an investment in capital assets that will generate long-term returns. “Much of that expenditure will drive a dramatic reduction in the $US3.7 trillion spent annually today on fossil fuel extraction and refining.”

He says governments will need to find a balance between the stick of carbon pricing and the carrot of subsidies, which accelerate investments in new technology. “To have impact on a world scale given the enormous subsidies available in other countries, support from the Australian government will have to be sharply directed and considerable,” he writes.

At the same time – and this is where Finkel’s optimism kicks in – technological improvements and cost reductions in solar panels, wind turbines and lithium-ion batteries have been nothing short of astonishing. “If it wasn’t for massive direct government incentives and investment in research and development, solar and wind electricity would not have come down the cost curve to the point where they are now cheaper than their fossil fuel alternatives.”

The nuclear question

Hydropower and nuclear power are and will continue to be globally important contributors, he says, but they lack the extraordinary growth rate of wind and solar: in 2021, solar and wind combined generated more than 10 per cent of the world’s electricity, up from 2.3 per cent 10 years earlier.

“That’s more than a fourfold increase in a decade,” Finkel says. In Australia, solar and wind electricity generation increased from 9 per cent in 2017 to 27 per cent last year. But behind all these glowing figures are mounting short-term problems – rising power prices, delays and cost blowouts to the Snowy 2.0 pumped-hydro scheme and the vital transmission line projects to get the clean energy to consumers. Industry figures are sounding the alarm and the energy regulator has aired concerns about future reliability gaps during the transition period.

I ask Finkel what is the most urgent piece of the puzzle. It’s transmission lines. “All indications are we would be moving even faster if it was easy to do transmission lines,” he says. “They are difficult in two ways. One is the time taken. It can be a decade or more to go from early thinking of where we might need a transmission line to actually going through regulatory process, financing and construction. If we could do that more easily it would speed things up.

“The other difficulty is that costs don’t come down like they used to for solar, wind and batteries. Transmission lines are mature civil engineering-type technologies, and their costs tend to go up with regulatory overheads, labour costs, and with the cost of copper and aluminium and steel that go into the transformers, and towers and cables. And then you run into the tension between the expectations of local landholders and the industry itself, and that’s a really hard one.”

To overcome opposition, early planning and negotiations with local communities and landholders are vital, he says, along with compensation. “If people can understand this is the most sensible route for the benefit of the local and state economy as well as a contribution to the national and global good, and on top of that they get reasonable compensation, then I think any reasonable person would agree at that point, if they don’t feel railroaded.”

From an electrical performance point of view, Finkel admires nuclear energy. “Nuclear power plants are superb zero-emissions electricity generators,” he says, ticking off the benefits. “I can understand that people can see the low resource imprint, the fabulous electrical characteristics of nuclear, and say: ‘Why don’t we use it?’ ” In some countries the argument for nuclear power is persuasive. But not in Australia.

Even if the federal government were inclined to pass the required legislation – and Finkel believes no government would do so without an election mandate – the time taken to debate the laws and design the regulations, identify storage sites and then commission and build a nuclear power plant would take too long. He can’t see it happening before 2040.

Why we won’t need nuclear

Small modular reactors, as mooted by the federal opposition, have benefits, he says, but would still run into social objections, timeframe and waste management issues and may not be as cost-effective as first thought.

“So when put together it’s not realistic, even if we wanted to, to have nuclear in Australia before about 2040, by which time I am quite confident we won’t need it,” he says.

By 2040, Finkel says, Australia will have an almost fully zero-emissions electricity system powered by wind and solar firmed by batteries, pumped hydro and hydrogen storage with the help of natural gas as a firming source.

“Given the trajectory of price reductions for solar, wind and batteries, it is likely that the cost per megawatt hour in 2040 will be lower than the historical average to date,” he writes. “Thus, any nuclear power plant switched on in 2040 will be competing against an established, low-cost reliable renewable electricity system. It will be a case of too little too late.”

Social and environmental objections don’t just stop with nuclear – how will anti-mining forces cope with an explosion in mining to extract the vast minerals needed for the clean energy revolution? On this Finkel is clear. The expansion of mining is crucial to the green energy future but must be ethical and responsible, and not come at the expense of local communities and the environment. “The ethics around that are non-trivial.” He says there must be robust regulation that can also facilitate industry.

“Simplifying and speeding up that process … is a daunting challenge that will require political commitment at the highest level,” he concedes.

We return to the vision outlined in the opening of his book: the vast solar and wind farms extending to the horizon, the long march of transmission lines, the explosion of new mines.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen put it bluntly last year: to meet our 2030 targets we will need to install about 40 seven-megawatt wind turbines every month until 2030, and more than 22,000 500-watt solar panels every day. The sheer scale of change. It’s a thought that some will find alarming.

“It’s certainly going to have a visual impact,” Finkel responds. “If it’s done well it can be minimised in terms of what it does to biodiversity and nature. So the regulators have to make sure the wind and solar farms, for instance, don’t just go to the most convenient spot but to places where they have minimal impact on local citizenry and biodiversity.”

It will require a careful balancing act and it won’t be easy. But he‘s clear that it must be done - greenhouse gas emissions have to be controlled. There’s another visual here, of wildfires destroying crops and homes, droughts drying up rivers and floods ravaging communities. Extreme weather events driven by climate change are punishing communities across the planet, he notes.

“We know what to do. We need to replace fossil fuels with zero-emissions electricity. Our ambition must be to usher in the Electric Age to replace the Industrial Age.”

Alan Finkel’s book Powering Up: Unleashing the Clean Energy Supply Chain will be published by Black Inc on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout