Canberra Consensus: learn to live with the debt bomb

Both sides of politics are avoiding dealing with endemic economic weakness.

The challenger wants to rumble with the titleholder and elevate his profile, given virtually all attention in coming weeks will be on Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese.

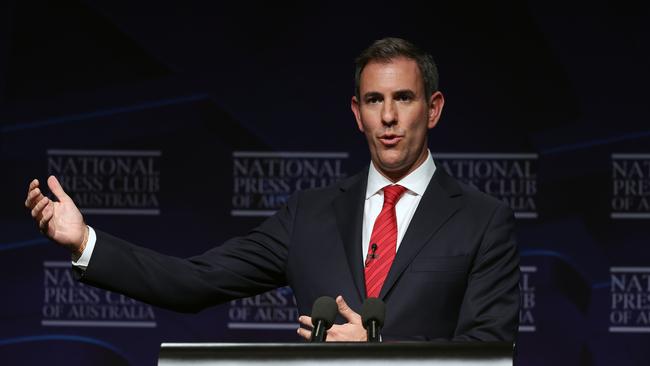

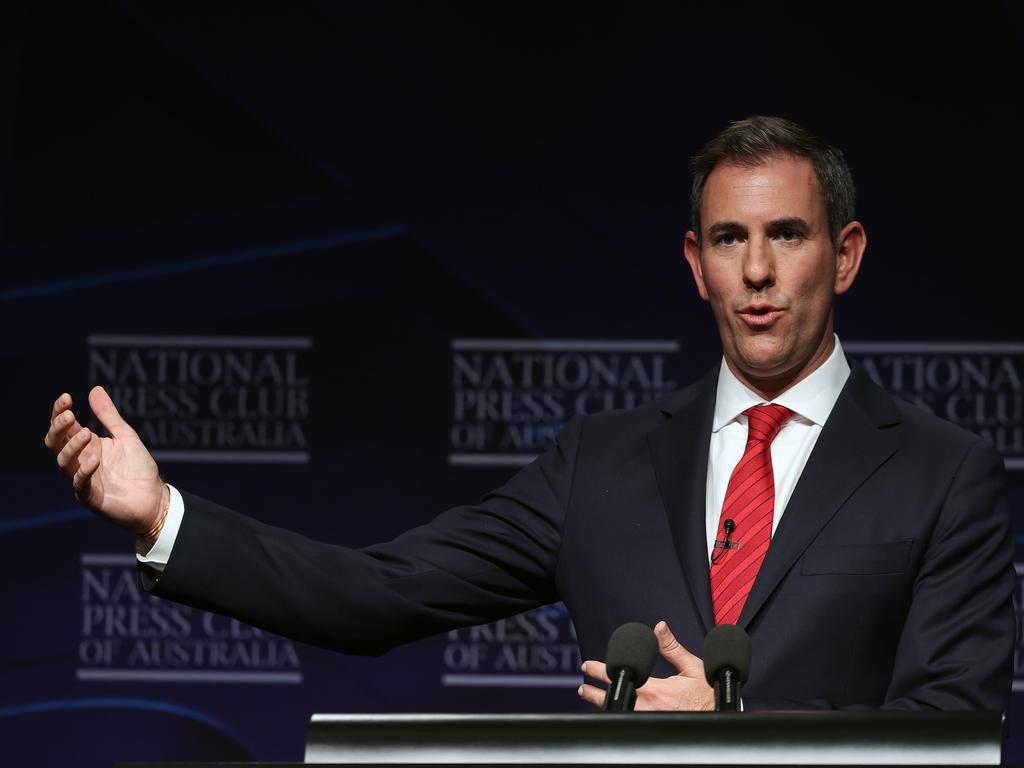

“I repeat my challenge to Josh Frydenberg,” Chalmers told the throng of Labor shadow ministers and staff in the Great Hall at Parliament House. “To debate the budget and the economy and the future – at least three times, here, in the west, anywhere we can make it happen.”

But what would they argue about, red versus blue ties? The beef or the fish?

On the eve of the campaign, the major parties are mirroring each other on economic policy, which was the main arena of conflict at the previous election.

According to the authoritative Australian Election Study prepared by the Australian National University’s Sarah Cameron and Ian McAllister, three factors shaped electoral behaviour at the national level in 2019.

First, management of the economy and taxation were key issues that benefited the Coalition. Second, Labor’s unpopular leader, Bill Shorten, cost the party significant votes because of a lack of trust. Third, while the environment was a major issue, with Labor gaining votes, it was not enough to outweigh the disadvantages on economic policy and leadership.

This election will see some differences in emphasis, say on childcare, skills, infrastructure, manufacturing and the digital economy. The competing paths in getting to net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 are within the margin of climate pragmatism.

But on taxing and spending, and the philosophies about how to run the capital’s control room, there is furious agreement on learning to live with the debt bomb and a small-target approach to reform. You could call it the Canberra Consensus.

Grattan Institute chief executive Danielle Wood believes the parties are consciously reducing the amount of economic policy difference, and that’s not ideal. “My fear is that we’re not having the bigger, harder and necessary conversations about the budget’s structural problems and increasing productivity growth,” Wood tells Inquirer. “I was hoping that as we come out of the emergency period that we would turn our mind to these important things.”

Ignoring these issues is fundamental to a strategy by the combatants to peel away voters occupying the centre and the disengaged. It also suits many career bureaucrats who are looking forward to “continuity with change”, as the satirists have put it. But this do-nothing accord won’t get us the “proper national conversation”, as Chalmers framed his “real talk” wish, about how to lead Australia to a better future.

This is dispiriting at every level. Frankly, the two “coming men” of politics – who are likely to be sticking around, know their way around the big issues and say they want to make a difference – are short-changing their parties and voters. It’s no secret our productivity growth has slumped or that, as our security threats rise and population ages, our finances are not sustainable. So why the silence on how to fix things?

The Treasurer’s latest budget, like the two that preceded it, has merged into the noisy traffic of the second-order issues and non-issues at large in the polity. With Labor waving through the fiscal bills in parliament in the last sitting week, it’s tempting rage to call it the first Frydenberg-Chalmers budget. Both men will hate the characterisation, but this is where we are at, as Labor tries to avoid a fourth straight defeat and the Coalition fears more voter backlash.

This term, Albanese eventually said yes to the Coalition’s stage three tax cuts; Labor also won’t tax family trusts in a different way. The 2019 measures to abolish cash refunds of excess franking credits and restrictions on negative gearing have been sealed in concrete and probably remain radioactive policies for at least a generation.

Chalmers has identified a malaise, of chronic deficits and wage stagnation, yet the best he could come up with at the National Press Club on fiscal policy was a series of easy-to-recite steps: “Grow the economy the right way; focus on quality and bang for buck; end the rorts and waste; and work with other countries to make sure multinationals pay their fair share of tax in Australia where they make their profits.”

Undoubtedly, any ALP marginal-seat candidate can rattle that off, compared with selling Bill Shorten’s vast program of social spending and the $387bn array of taxes to fund it. As the ANU political scientists concluded about the 2019 result, “at the end of the day, Labor was unable to convince voters that the increased taxation they proposed would lead to greater economic prosperity”.

The world has since been up-ended, but not our endemic economic weaknesses or the tendency of the political class to avoid dealing with them. To be fair to Labor, they’re on a unity ticket of denial with the Coalition.

The freewheeling crisis spending of the pandemic, more than $300bn in direct stimulus, and the Reserve Bank of Australia’s free money have delivered a labour market miracle and, stoked by global events, rekindled inflation after a three-decade hiatus. The RBA has dropped its “patient” guidance and as soon as it sees a growth pulse in wage setting it will start raising interest rates, most likely in June.

Covid-19’s legacy is bigger government and smaller thinking. Only the Coalition could have secured the political cover for such a Whitlamist expansion, after Labor’s bitter experience in botching the timing of its global financial crisis responses.

All orders of magnitude have been blown out by the pandemic and so has the Coalition’s fiscal discipline and inclination. Prudence has given way to pragmatism, if not profligacy. The heirs to John Howard, Peter Costello and Mathias Cormann have transformed the fiscal universe.

Much of Frydenberg’s spending was indeed “temporary, targeted and proportionate”, but a lot else has been going on this term to shore up marginal seats and feed the junior Coalition partner’s white meat eaters.

For one, dumping more infrastructure spending into a pipeline the construction industry can’t cope with will lead to delays and higher costs to taxpayers. That’s before any consideration of project merit or need, which has become adulterated.

Wood says we’re coming out of the pandemic with significantly higher permanent spending. Canberra has baked in elevated outlays on aged care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme and defence, “without thinking about how you’re going to pay for that”. She estimates outlays are now $60bn a year higher than planned at the 2019 election. If opinion polls are right, and Labor wins next month, strap yourselves in for more of the same under Albanese-Chalmers.

The only wriggle room Labor leaves itself is to ditch the arbitrary tax cap of 23.9 per cent of gross domestic product the Coalition has imposed on itself (which was the average of the Howard years).

Naturally, the Prime Minister has gone to town over his opponents’ disregard of the “Cormann line”, warning Chalmers “wants to let taxes rip, he wants a no-limit tax policy”. Labor doesn’t have to introduce new taxes, just allow the personal income tax take to creep up with wage inflation (if it ever arrives) to pay for more spending down the track.

Why will anything improve after the election, as some naively think? Will an export-price windfall wash up on our northern and western shores to buy off some reform measures? Perhaps only another crisis, this time from a weaker fiscal starting point, will shake the nation out of this complacency. But don’t waste your crypto on it.

The Grattan Institute published a broad reform plan ahead of the budget. Wood says governments could help by not doing wasteful things such as putting stimulus into an economy where unemployment is about to hit a 50-year low and to avoid low-grade infrastructure projects, especially when the construction pipeline is bloated.

Wood argues a structural reform agenda is vital if we are to revive our productivity growth. While governments can’t do it all on their own, she says they need to do what they can.

As former Australian Competition and Consumer Commission chairman Rod Sims said in his valedictory speech in February, a good place to start would be to ensure stronger competition between firms.

Given there’s little chance of “big bang” moves on workplace arrangements or tax reform, the next government should look for less controversial, incremental change that is not necessarily costly. Wood points to Grattan’s work in reviving skilled migration and policies to achieve better outcomes in health and education that don’t require costly spending, just better thinking.

The major business lobbies also have been nudging for greater policy ambition, with the Business Council of Australia this week putting out a paper, Seizing the Moment. Fiscal sustainability and investment breaks head the wish list, but there are also the perennial requests for workplace reform, clean energy transition and competitive company tax rates.

BCA chief executive Jennifer Westacott argues there’s a danger we’re heading for a “zero mandate election”. But after sampling opinion around the country via policy roadshows, she believes voters want more than stasis or a race to nowhere.

“Overwhelmingly the Australians we’ve spoken to are optimistic about the future, they’re up for the reform needed to make ourselves a stronger, more resilient nation,” says Westacott. “Every decision we make as a nation must be about building productivity, driving new industries and making ourselves more competitive.”

With an election imminent, the miserable fiscal and reform non-aggression pact will not serve Australia well. Like Dusty sang in the northern summer of 1964, Morrison and Albanese are “wishing and hoping and thinking and praying” that the credit line that saved our skin in the pandemic and feeds our exceptionalism does not dry up.

In his speech to the National Press Club this week, treasurer-in-waiting Jim Chalmers dared the incumbent to front up to a series of economic debates during the election campaign.