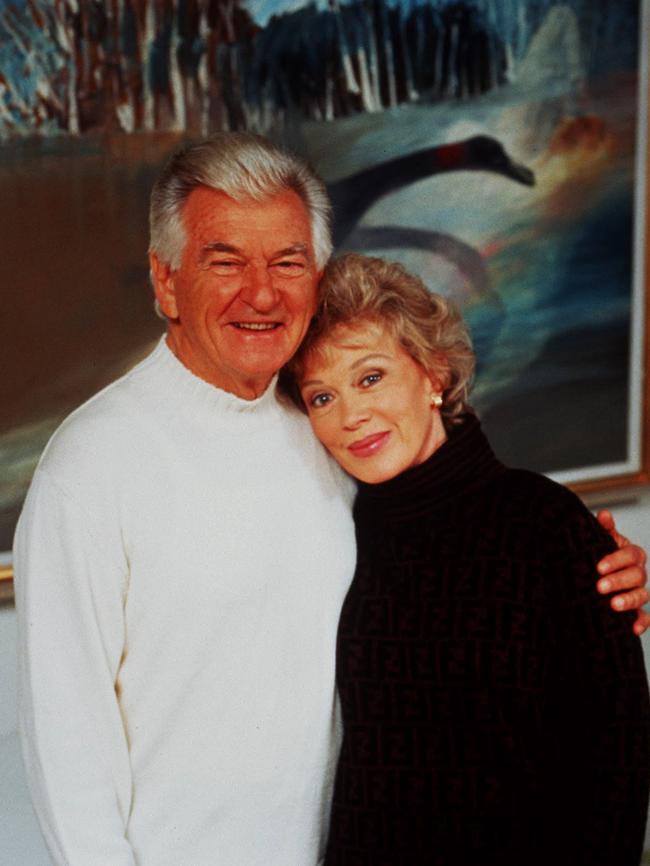

Bob and Blanche: An affair for the ages

Bob Hawke’s widow Blanche d’Alpuget opens up on an affair for the ages.

They met when Blanche was 26 years old and Bob was 40 — they loved, broke up, got back together, separated, then reunited. Bob Hawke was driven by his compulsion for her and Blanche d’Alpuget lived the full cycle of love — from sexual excitement to intimacy in his dying.

“I have a very deep belief that love is the most important thing in personal lives and in the world,” Blanche said in an interview this week. “And that fact that I truly loved him was the most important thing — it took priority over everything else.”

As a writer, feminist, lover and wife, Blanche d’Alpuget’s extraordinary life is testimony to how a woman can be truly independent yet make sacrifices for the man she loves. Our interview is about the eternal themes because they dominate Blanche’s life — love, sex, sacrifice and death.

Bob died at home on Thursday, May 16, two nights before the election. “He was really keen to die,” Blanche said. “He was 100 per cent reconciled. And he was peaceful at the end. What he said is, ‘I’ve contributed everything that I can.’ ”

Interviewed at the multi-level Northbridge home they shared, Blanche rejected the baby boomer stereotype about the destruction of dignity in dying.

“Bob always kept his dignity,” she said. “It never left him. Even when he couldn’t shower himself, even when he was so dependent he had to be showered and dressed and shaved by his carers.

“Truly, Paul, this may sound odd, let me say this last year to nine months while he’s been dying have been the most tender and intimate of our whole lives. It has been for me the wild excitement of sexual ecstasy to the great tenderness of looking after a person who was completely dependent upon me.

“And there was much greater intimacy actually in looking after somebody who is in that debilitated state than there is in even the wildest sex.”

Does she yet feel the spiritual connection with him in death?

“Not yet, I certainly don’t yet. I may in the future. I am a spiritual person. But what was wonderful was the moment he died I felt this absolute lightness, the light around him, and spirits lifted, and suddenly no more worries, no more cares, no more anxiety, it was marvellous. It was absolutely wonderful.”

D’Alpuget paid a high price as the “other” woman in the breakup between Bob and Hazel Hawke. The vilification was intense. “I was shocked by it because I was so much in love. I wasn’t really aware of it until a friend of mine, a writer, said to me, ‘Oh Blanche, the rancour against you, it’s unbelievable.’

“And then soon after that Bob and I were walking through the airport to go somewhere and (he) said to me. ‘There’re very angry.’ But I was able to cope with it because love in that situation can be a great protection.”

Asked about the force between them, Blanche said: “I think it actually was destiny.”

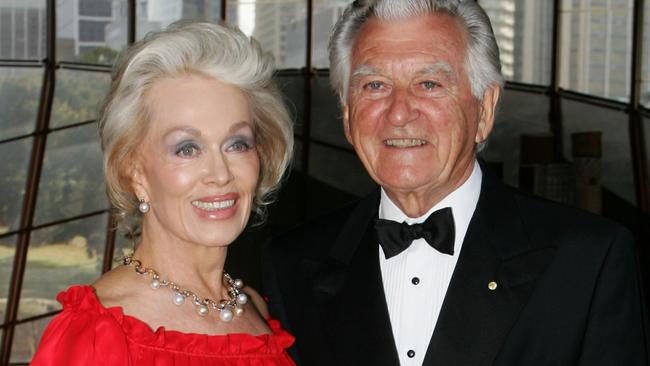

The pair married in 1995 — it was a love affair but Blanche says “it was also tumultuous because he started drinking again. I didn’t like him when he’d been drinking. We used to fight over that, like cats and bloody dogs.”

Were they faithful to one another? “Yes,” she said. That was important, “especially for both of us, both of us were very sexual people, and there was something we, each in our own way, really had to struggle with, not looking sideways.” Did Blanche, as a wife, trust Hawke? “Yes, I did.” The drinking moderated over time. “It came and went,” she said.

In the end Blanche was a carer, a role she invests with nobility.

“He lasted almost a year longer than I thought he would,” she said. “Two days before he died we had a very good friend over here and he said to her, ‘It won’t be long now.’ He knew. That was on the Tuesday and he died on the Thursday at sunset on a waxing moon, which was really lovely.

“He reached a stage called ‘anhedonia’ — that is, a lack of pleasure in life. And the medical professional — God bless them — tries to medicate this by giving people antidepressants. One doctor did — he took one — (she laughs) even though you are meant to — they don’t work unless you take them for two weeks — but then he threw them out and said, ‘This is rubbish.’

“He knew he was not depressed, he knew he was wanting to die. He used to say very often, ‘Oh I wish I could die’ or ‘Oh I hope I can go to sleep tonight and not wake up.’ But dying is harder than that.

Bob died at home in the presence of Blanche, his former adviser, Craig Emerson, to whom he was a father figure, and Craig’s partner, Tracey Winters.

“I was holding his hand, and Craig was standing on the other side of him watching the pulse in his neck because his breathing was strange,” Blanche said. “It would often stop and start again, and then it stopped. I said, ‘Craig, quick, feel his neck’, and he felt his neck and there was no pulse. It was very sudden. It was after dinner, he suddenly got pain. We would normally have watched some of 7.30 and we just got up from the table and came in and he lay down here (in the main room) but then his pain got worse.”

But Hawke, a warrior, had also fought to live. “He was very close to his stepson, Louie, my son,” Blanche said. “We had their engagement party here and then they announced they wouldn’t be getting married until May this year. Bob said, ‘I’m going to live for that.’ And I thought and everybody thought, ‘No way will you make it.’ But it was just determination.

“And it was very beautiful. It was in a forest on Mount Wilson. They’d taken a baby grand piano into the forest, it looked wonderful, we were all wrapped up and freezing. Forty kilometres away at Jenolan Caves it was snowing. He went up and back in the day. It was arduous. He couldn’t stay for the reception that night.”

What happens to Blanche d’Alpuget after Hawke’s death?

“I go back to what I was before him — that is, I’m a writer.” In truth, she has never stopped being a writer, though she did put writing on hold to dedicate herself to their joint life.

“At this very moment I feel as if I’ve been run over by a steamroller,” she said. “I expect once this grieving period is over — and I don’t know how long it will last — that I will resume writing with the great joy it has always given me.

“Perhaps I should add this. It was a full year in which he was steadily, steadily, steadily going downhill, I had the wonderful escape of vanishing into the 12th century — the House of Plantagenet” — a reference to the books Blanche is writing on the family that held the English throne from 1154.

“Yes, the birth of the Plantagenets, and I used to do that while he was asleep in the morning. I used to go to my office and I would leave the 20th century and go into the 12th century, and it was marvellous, in my office in Cammeray, just six minutes away.

I did a great deal of my grieving over many months when he had a stroke last year. I was beside myself. I weighed four kilos less than I do now. I couldn’t sleep, I burst into tears all the time. I am still doing that if anyone is sympathetic to me (crying). I just want people to not be sympathetic at the moment.”

The affair between Bob and Blanche began when she was writing her biography of Sir Richard Kirby, the long-serving president of the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. At this point we moved to the Bob and Blanche narrative:

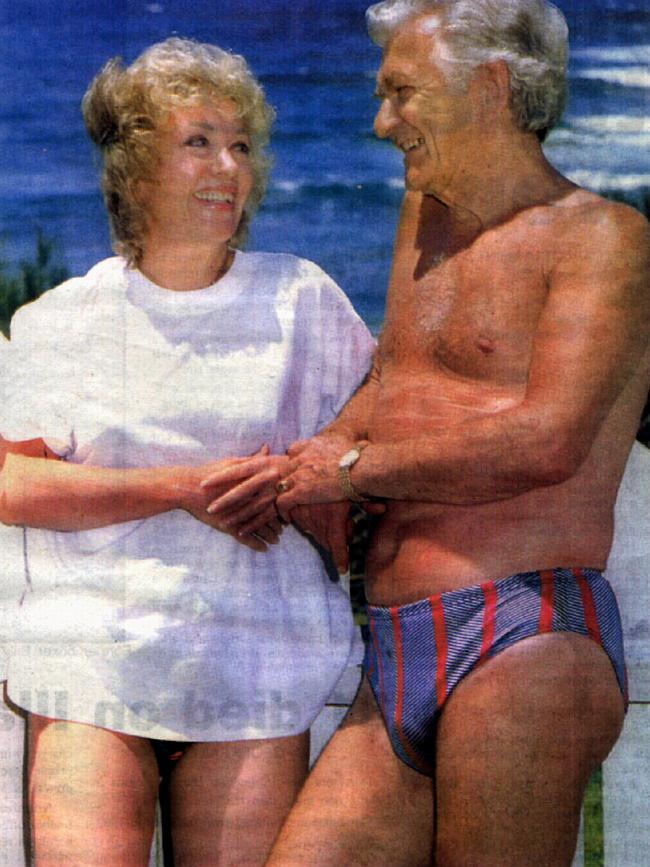

Q: You met Bob when you were in your 20s in Jakarta?

A: I was 26, he was 40. He said I looked like a movie star (laughs).

Q: There was a connection from the start?

A: Yes, yes. But it wasn’t sexual at all. I was impressed with his character. I might say he had different feeling towards me (laughs) but I hadn’t been married long to Tony and I was very keen on Tony. (Blanche was married to Tony Pratt, a commonwealth intelligence operative at the embassy).

But Bob came up again the following year. And he made his feelings towards me very obvious, unfortunately in front of about 20 people. We all pretended he hadn’t said it.

I don’t know if I should say this but he said to me, “I want to f..k you” (laughs). In front of a room full of diplomats. Everyone ignored it including me. He had had, I might say, one or 20 bottles of beer. And my husband was sitting right there beside me.

Q: Did you see much of him after that?

A: Not until I did the Kirby book. I had no idea about his career until I started work on the Kirby book and then I read these wages cases and I saw what a smart guy he was. I interviewed him a number of times.

Q: Is that when the love affair started?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you feel this man could be the love of your life?

A: No, not at all. He was just too wild. He was married, he had three kids, I was married, I had a young son. It was just not something I was going to consider.

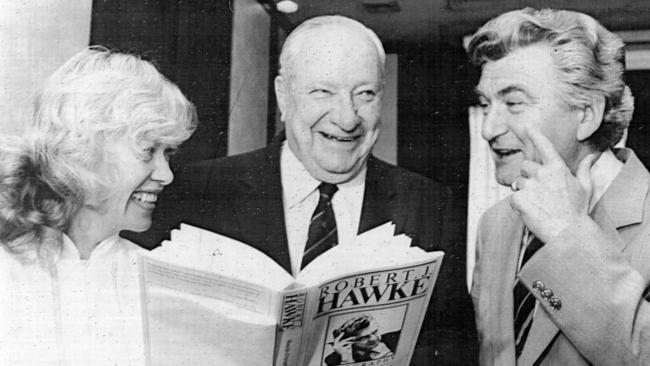

Q: What influenced you to write the Hawke biography?

A: It was funny. I wanted to write the biography of Albert Monk, the first president of the ACTU. I wrote to his widow and she refused to co-operate for this extraordinary reason: she was his second wife and she didn’t want people to know that. So I thought, ‘Oh well, I’ll try for the second president’, and that was Hawke.

Q: What did you feel about the ethics of it, writing a book about Hawke but being in a sexual relationship with him?

A: Well, before I started the book we busted up. Because it had become very intense and by 78 — I think it was August 78 — we busted up.

Q: But I think it was in 78 that he asked you to marry him. What was your response?

A: I said I’d think about it, and I did think about it. I sought advice from a close friend, who said, ‘Do you really want to marry Bob or do you want to leave Tony?’ and I thought, ‘No, I really want to leave Tony.’ But I was still terribly cut up when I came back to Bob and said, ‘Yes, I want it’ because I’d left, I’d left Tony.

I decided I wanted to marry Bob and he and I were still talking as though it was going to happen, and then he rang me out of the blue and said it seems I’ve got a brain tumour (laughs). He was just so out of his mind with distress over his career, his family, politics, what was going to be the next stage of his life.

Q: At some stage Bob said getting divorced would cost 3 per cent of the vote?

A: Yes, he did say that.

Q: You were resentful, you had to be resentful?

A: Resentful is the wrong word. I was furious and I felt betrayed. Initially I took a lot of that anger inward and I wanted to commit suicide. But that didn’t last more than three days. And then I pulled myself together and thought, “What’s the intelligent thing to do?”

Q: And what was the intelligent thing to do?

A: His biography. I remember my very first lover told me many years ago — he was older than I was — that if something terrible happens to you — he was Polish and plenty of terrible things have happened to the Poles — that if something terrible happens to you, write it out. And I thought, “The moment has come.” Funnily enough, that man is still in touch with me.

Q: It’s almost as though you were playing a role in his prime ministerial quest?

A: Not consciously. I had friends who said to me, “This is a campaign” and I said, “No, it’s not.”

Q: How did you feel when he won the election in 83 and became prime minister?

A: I felt very cold. I was living in Jerusalem and it was snowing, like my hot water had gone off (laughs). I had to go to Tel Aviv to vote. I got back to Jerusalem, wanted to have a hot bath and it was freezing cold. I knew he’d win. As soon as he became leader I knew he’d knock over (Malcolm) Fraser and I said so at the time. I said Fraser had stabbed into what he thinks is a straw man and he’s hit metal and it’s Hawke.

Q: It seems to me, Blanche, that once Bob became prime minister, he needed you again.

A: Possibly. He rang me up in Israel, yes. Dunno know how he found my number but he did somehow, yes.

Q: And you started seeing him again when he was PM?

A: Later, well, not until I got back to Australia clearly — yes. A little bit and then he had all the drama in 1984 and then that was it. Cut off.

Q: That was a time of trauma in his life, 1984, with his daughter and the drugs. Did you think that was probably the end between the two of you?

A: Absolutely, yes.

Q: How did you feel about Bob after that?

A: I tried not to think about him.

Q: Were you resentful?

A: No.

Q: But remember you wrote an article about him, you interviewed him, but you talked about him being a shrunken prime minister. What’s the psychological story there?

A: Paul, well, I don’t remember the piece. I guess he had shrunken in my life, in my mind, so I was probably projecting on to him, which we all too often do, project our own feelings into other people — and they’re inaccurate.

Q: But you were missing his prime ministership, you weren’t in his life for this middle part of his prime ministership. The two of you must have talked about this later when you were together and married?

A: We certainly didn’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about it at all. I mean friends of his have told me that he told them how much he missed me during that period. But he has never said that to me himself. Cool cat, yeah, cool cat.

Q: You divorced Tony, I think in 1986, so what sort of life did you think you were going to have then?

A: Well, I was a writer, I was getting on with my life. I’m not one of those woman who has to have a man there to lean on.

Q: But Bob couldn’t stay away in the end, he came back to you.

A: That is true.

Q: This was in 88 or 89?

A: Soon after the Kirribilli Agreement.

Q: I always thought there was something interesting about this; he came back to you when he was in trouble with (Paul) Keating on the leadership, when it started to come into play. Am I right?

A: I think it was when he saw the prime ministership was starting to come to an end. He knew that he couldn’t survive and although he was going to go on fighting because he’s a war lord — he and Keating were both war lords — and, well, I don’t think that he thought, and neither of us thought, that we would be able to get married. Because I still had other lovers and, as far as I know, he had other lovers too.

Q: At what stage did marriage become feasible or a possibility?

A: I was doing a piece for The New York Times, a travel piece. I was up in north Queensland staying in Hayman Island, meant to be flying out to the Barrier Reef and the plane crashed. We had to swim out of a window. And our go-between rang up Bob and said, “Blanche has been in a plane crash,” and Bob said he felt himself die. And then the friend added, “But she’s all right.” That moment Bob knew he had to end his marriage to Hazel, which was really very hollow by then. Their marriage had been for the great purpose of having children and him being prime minister and her being the prime minister’s wife. They’d done all of that together. So, he knew at that point that it was over.

Q: So that was a near-death experience for you?

A: Yes, it was — but I took my handbag with me (laughs), swimming out the window, you know how they always say “leave everything”. I love this handbag.

Q: So what did you feel, you’ve described what Bob felt?

A: Oh, it’s a fantastic thing to be in a plane crash and survive and not be seriously injured. I was covered with bruises. There’s a sense of elation that you’ve avoided death, that’s what I felt. I did want him told immediately, so I immediately thought of him. I didn’t want him to pick up the papers and read that I’d been in a plane crash, little knowing how unreported those things go.

Q: When was the plane crash?

A: I think it was the 24th of June, 1993.

Q: And he proposed at some point that you get married?

A: After that, yes. I said yes but he had to get divorced first. Paul, you understand, I’d been through this before. So I was waiting to see what happened, if he actually would get divorced.

Q: You still had a few doubts?

A: Yes.

Q: You had serious doubts?

A: Of course, I’d be a fool if I didn’t.

Asked if she had felt guilty, D’Alpuget asked: “About what?” I replied: “About the situation.” She didn’t. Blanche said after they were married “we did have a few family gatherings at which Hazel and I were present and it was perfectly amicable”.

“I did feel a great deal of sympathy and even pain for Hazel. You asked me about guilt, did I feel guilt, and I said no. But when two women love the same man there is a certain sisterly feeling. I was very, very good friends with one of Bob’s favourite mistresses.

“There’s that French song, La Vie en Rose, and one of the English translations is ‘taking me to your arms again’. And when I would sing or hum that I would always be thinking of Hazel.”

Bob died an agnostic but Blanche said he was “actually very spiritual” (laughs). Did he think there was an afterlife? “He was genuinely agnostic. He didn’t know,” she said.

For Blanche, love is the key that reconciles her independence with her sacrifices for Bob. “Love is our greatest reward. Love is the zenith of life. And because of that I was willing to give up writing.

“Bob gave me a lot of kudos. I was a director of the company. I travelled with him everywhere. And a whole lot of people insisted on calling me Mrs Hawke, not Blanche d’Alpuget (laughs). It was just water off a duck’s back really.”