Beijing’s man in Australia Ruan Zongze explains what Xi Jinping wants from Canberra

Consul-general Dr Ruan Zongze is one of the most interesting diplomats to be posted to Australia, and says diplomacy should ‘give us some more wisdom’ to navigate differences.

Copies of Xi Jinping’s four-volume opus, The Governance of China, greet visitors to the People’s Republic of China’s Brisbane consulate. My interview request with their author remains a work in progress, so instead I am here, on this sunny autumn day, to interview Dr Ruan Zongze. He is one of the world’s leading authorities on the official doctrine Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy.

Ruan is an influential figure in Beijing’s foreign policy establishment and one of the most interesting diplomats to be posted to Australia. This is his first substantial interview since becoming China’s Queensland consul-general in June last year. Our two-hour conversation contains some promising news, some unsettling news and perhaps the most candid public assessment ever given by a Chinese official on the shaky foundations on which the China-Australia relationship is built.

“Australia and China, we don’t have much trust in each other,” Ruan tells Inquirer. “We have so much deficit, so much deficit on this. And anything, a little thing happening here, we just are so sceptical about the other side’s intention. And vice versa. I’m not just blaming Australia. This is not normal, right? We don’t have such a very mature communication and such kind of consultation.”

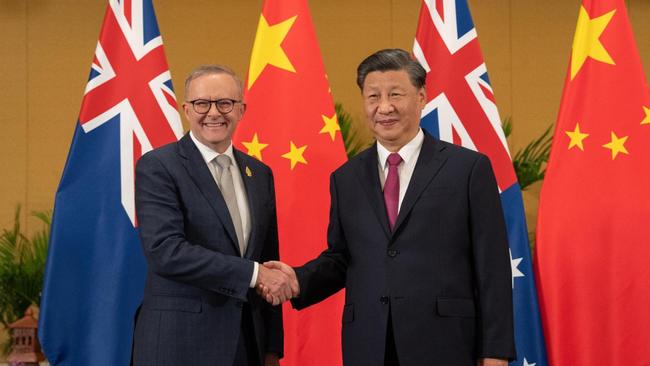

After five bruising years during the Turnbull and Morrison governments, followed by 15 months of the Albanese government’s “stabilisation” project, Australia’s relations with China are in a delicate state.

Senior Chinese officials are visiting Australia again. This week the first shipment of Australian barley was sent to China since the lifting of a 80 per cent tariff.

But sources of friction remain plentiful. A fortnight ago, Anthony Albanese oversaw the chiselling of AUKUS into the Labor Party’s national platform. In recent days Australia joined the US and Japan for a combined navy drill in the South China Sea in waters China claims off the western Philippines.

Canberra is trying to put the relationship on a more pragmatic footing as it embarks on uncharted territory. “We don’t know what the new normal will look like,” one senior Australian official says. “But I’d much rather be where we are now than where we were two years ago.”

A ‘chilly, dark’ posting to Brisbane

Ruan is worth a close listen. Until weeks after Labor’s election victory last year, he was vice-president at the China Institute of International Studies in Beijing, overseeing research at the influential brains trust for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

He is one of the Communist Party’s most prominent foreign affairs intellectuals, the author of books on international relations including 2019’s What Does China Want?; a regular writer for the party’s most authoritative newspaper, the People’s Daily; and a talking head on Beijing’s flagship broadcaster CCTV.

The posting of one of the Chinese government’s best foreign policy communicators to Brisbane shows Beijing is at least trying to improve relations with Australia.

When the Sichuan-born, Renmin University-educated envoy arrived in June last year, he was braced for hardship. He had been following – and commenting on – the implosion of the Australia-China relationship from Beijing.

“I prepared psychologically before I came for a very chilly, dark (posting),” says Ruan. “All of a sudden it’s sunshine. And also nice people … So that’s a little weird, but great for me. I find this is a very relaxing and a good place.”

Ruan previously served as a diplomat in London during the Blair era and Washington during the Obama era. He published books on both experiences. An Australian book may be next.

“If there is an opportunity I would love to because I have to do the AUKUS trilogy,” he says with a grin.

‘A piece of waste paper’

Viewed from Beijing, Australia’s insecurity about a rising China can seem perplexing. Australia’s geography – a continent-sized island, with no land neighbours – is the stuff of a Beijing strategist’s fantasy. China, by contrast, has 14 neighbours, many with nuclear arms and thousands of years of bad history.

“Each of them is difficult. You know, it’s easier to love (all) human beings than to love your neighbour,” Ruan says, laughing.

As its navy has grown, so have China’s maritime territorial disputes, particularly with Japan, Vietnam and The Philippines.

Ruan says China’s “overwhelming agenda” is its modernisation: “We want a prosperous, strong China.”

That will require a “benign world environment” and for China to better explain its goals: “People will have concerns about a growing and stronger China.”

Beijing’s hardline approach to territorial matters is stoking those concerns. China has refused to accept The Hague Tribunal’s South China Sea ruling against it in 2016 over a maritime dispute with The Philippines.

In What China Wants, Ruan applauded Beijing for turning the ruling into “a piece of waste paper”. Canberra had a different view of Beijing’s rejection. It saw a disturbing demonstration of might-is-right by the region’s rising power.

Ruan says China will never accept the decision of the international court on the matter – unless the court finds in Beijing’s favour.

“China will very much insist on its own position. We will never ever recognise the so-called arbitration,” he tells Inquirer.

Beijing is similarly dismissive of the Biden administration’s calls for China and the US to establish “guardrails” to avoid a military escalation.

The Australian government has prominently supported Washington’s efforts.

“This isn’t about a policy of containment … This is a matter of simple, practical structures to prevent a worst-case scenario,” the Prime Minister said in his keynote address to Singapore’s Shangri-la Dialogue in June this year.

Beijing disagrees. Ruan says guardrails will allow Washington to operate its military near China’s coastline without concern. “America will be even more provocative and never take what China thinks very seriously,” he says.

Who speaks for AUKUS?

The American factor looms large in Beijing’s world view.

“China’s relations with the United States of America, like it or not, has had a very strong influence on China’s foreign policy, and also on how China looks at the rest of the world,” Ruan says.

Washington’s sharp turn on Beijing has meant that, while China is richer and stronger than it has ever been in the modern era, it is also riddled with insecurity.

Ruan says the AUKUS defence technology partnership has saddled Canberra with the even bigger distrust China has with the US.

“Even if the Australian government approaches China and says, ‘Hey, this is my plan, my intention about this’, but almost at the same time the Americans say something very different, who shall we listen to?

“You have three voices. They’re not always compatible with each other. This is a problem.”

Take the recent call by US congressman Mike Gallagher, while in Australia, for AUKUS to “adopt a war footing” to “wage peace”. It was not language any Albanese government minister would use.

Ruan says Defence Minister Richard Marles’s recent argument at Labor’s national conference that the AUKUS submarine fleet was necessary because of the build-up of the People’s Liberation Army was “very unconvincing”.

“Put yourselves in China’s shoes,” he says, listing the US military bases surrounding his country. “Yes, China’s military is catching up. It’s modernising. But the purpose is quite clear. We will defend our national sovereignty and territorial integrity – particularly vis-a-vis the Taiwan issue. It’s not going to invade any other countries.”

The Hong Kong solution for Taiwan

Unlike most Chinese officials, Ruan has visited Taiwan. He has visited “three or four times” while working as a researcher, between diplomatic assignments.

As we discuss Beijing’s plan to bring Taiwan’s 23 million people under the Communist Party’s rule, no effort is made to reassure Australians, let alone Taiwanese, about China’s intentions – quite the opposite. Beijing’s threat of war against Taiwan should it declare formal independence is part of the status quo.

“We make it very clear, very clear,” says Ruan.

Shortly before our interview, the People’s Liberation Army had again circled Taiwan with jets and warships after Taiwanese Vice-President William Lai transited through the US on his way to Paraguay, one of the 13 countries that officially recognise Taipei.

Lai, a figure loathed in Beijing for being an “independence worker”, is the favourite to win next year’s Taiwanese presidential election.

“The fundamental tension comes from Taiwan authorities. They want to rally American support for their own independence agenda and challenge the sovereignty and territorial integrity of China. And the United States, on the other hand, is also using Taiwan to contain China. So China must be prepared for the worst-case scenarios,” Ruan says. Beijing is not eager for war, but it is pitching a deeply unpopular alternative: “One country, two systems”, the model first used in Hong Kong.

Even before Beijing’s snuffing of political freedom in Hong Kong, it was a model rejected by all of Taiwan’s mainstream political parties.

I moved to Taipei in 2021 and still haven’t met a single person who supports the idea.

Ruan says the unpopularity of the concept in Taiwan does not matter. “There is no alternative,” he insists. “What about the 1.4 billion (Chinese) people?”

China’s Australia problem

Despite the friendly reception for Ruan as he travels around Queensland, surveys show Australians remain as wary about China as anyone in the world. Eighty-seven per cent of Australians told the Pew Research Centre they had an unfavourable view of China. Only the Japanese rated China as poorly.

Official Chinese media has admitted the bad will in Australia has “proven to be sticky”, but Beijing seems unsure how to address it. China has no record of repairing its reputation with a liberal democracy with which it has had such a spectacularly fallout. Sentiment towards China remains woeful in Japan and South Korea after Beijing waged coercion campaigns against them starting in 2010 and 2016 respectively.

Ruan concedes Beijing’s sweeping trade strike campaign has not helped his country’s reputation, but he asks that Australians consider why China used this “double-edged sword”.

He says Beijing felt it had to act because of the Turnbull government’s Huawei ban and the Morrison government’s Covid-19 inquiry call. “The last (Australian) government, they wanted to be the spokesperson of Washington.

“That sort of thing really put China in a very difficult position … Can you advise me some better way to respond? I know it has hurt. It’s a double-edged sword.”

Senior Australian government officials have a different interpretation of the source of the breakdown. One says China wanted Australia to be “a bit of an antipodean Cambodia”.

Beijing has unwound most of its trade restrictions, although Australian wine and live lobster remain on China’s blacklist. Australians Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun remain in prison in Beijing.

If he can find time in his diary, Foreign Minister Wang Yi – returned to the job after his successor Qin Gang “disappeared” – is expected to visit Australia to clear the way for a trip to China by Albanese before the end of the year.

‘A lot of homework’

Ruan says it is important Australia and China do not “pretend we agree on everything”, and says diplomacy should “give us some more wisdom” to navigate differences.

The complementarity of our economies also helps. From almost nothing in 2020, Chinese firms imported $11.7bn of lithium from Australia in the first half of this year, overtaking liquefied natural gas as our second most lucrative export to China. More than 90 per cent of Australia’s lithium goes to China.

Chinese students continue to enrol at Australian universities in unmatched numbers. The first plane-load of Chinese group tourists since the industry was shut down by Covid arrived in Melbourne last Thursday and Chinese tour operators say Australia is a popular destination among those planning “Golden Week” holidays next month.

“Our trade, economy, education, even tourism, just name it – you guys have something really good to offer and China really needs it,” says Ruan.

He wants the two countries to be “even more bold in our vision for this relationship” and look for ways to work together with other countries in the region.

Instead of a source of security angst, he says the Pacific Islands should be a region for “China plus Australia” co-operation to help other countries develop their economies and mitigate damage from climate change.

“Australia has a lot of ideas. You have a lot of traditional connections with the region and with the Pacific.”

China, now the world’s second biggest economy, sees itself as a natural development partner for the region. Beijing is understandably proud of overseeing the biggest poverty alleviation in history: around 800 million people in the past 40 years.

“We want to share these kinds of opportunities for them. That does not mean China is a teacher to them. No, not at all. Just equal partners.

“We need to join your hand to do more such factual work, rather than very abstractly debating about national security.”

But as Ruan concedes, pursuing a bold positive vision is impossible without trust.

“We have a lot of homework,” he says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout