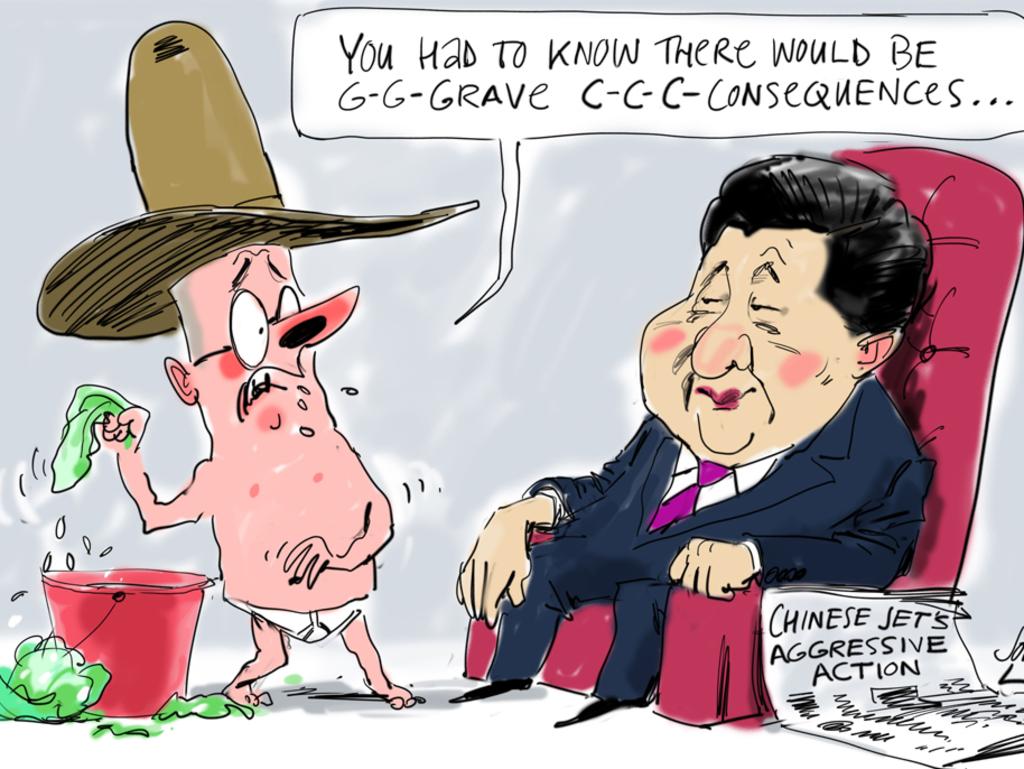

Beijing escalates its sinister game of chicken

In an exclusive interview, US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell sketches Washington’s frustration at Beijing’s irresponsibility and fears of further escalation.

In an exclusive interview with Inquirer following the May 4 incident when a Chinese air force plane dropped flares in the path of an Australian helicopter taking part in a UN sanctions patrol in the Yellow Sea, Campbell makes it clear Beijing’s aggressive behaviour is accelerating and dangerous.

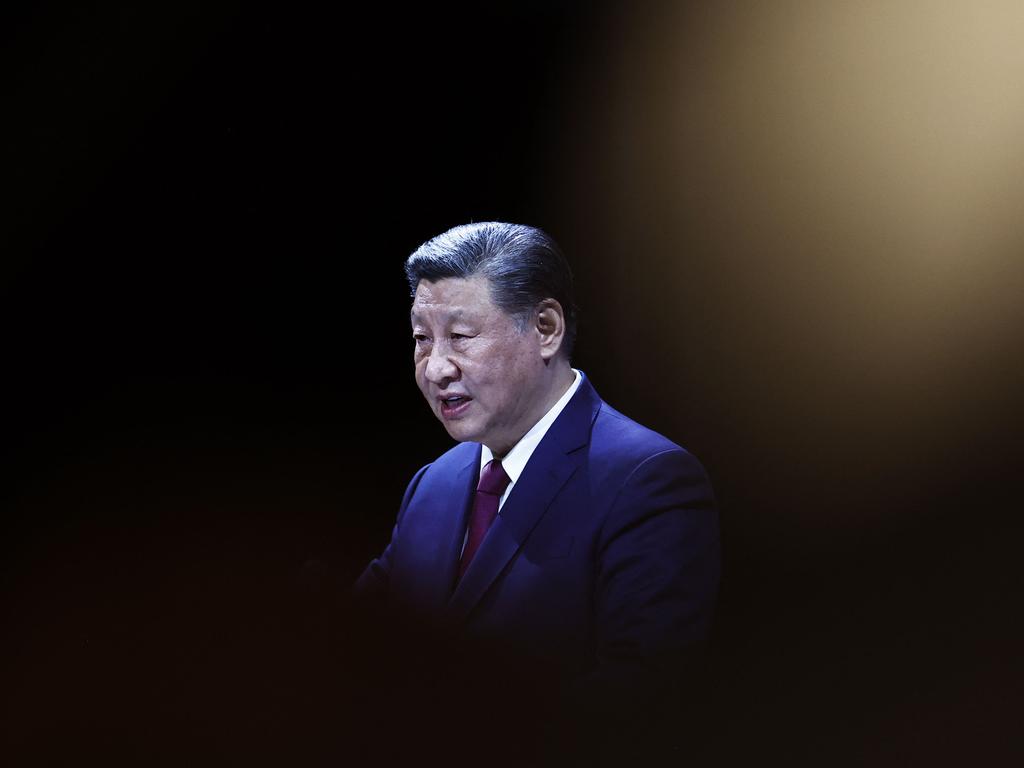

“China’s military under President Xi has increasingly been emboldened to challenge US allied naval and air assets using an array of tactics and capabilities, including unsafe navigational practices, flares, high-powered lasers and water cannon,” Campbell says. “These incidents occur in international air space and waters near China.”

Campbell’s words indicate that Washington is increasingly concerned at the high level of risk that these Chinese military actions embody.

“These manoeuvres risk inadvertent escalation and unintended accidents,” Campbell tells me.

The US is intensely frustrated that Beijing has resisted measures to make sure there are no accidents at sea and no unintended loss of life.

Says Campbell: “The US has sought increased military-to-military engagement and crisis-prevention procedures with China as a precaution to prevent a direct military clash that could result from these practices.”

Campbell, who was formerly Indo-Pacific director in President Joe Biden’s National Security Council, before being promoted to Deputy Secretary of State, is the leading US senior official on Asia policy. He expresses strong solidarity with Australia in the wake of China’s latest military provocation: “We consult closely and co-ordinate actively with Australia on our respective encounters with Chinese warships and fighters in these circumstances.”

Campbell’s comments to Inquirer indicate just how seriously the Biden administration takes Beijing’s military provocations.

There have been four publicly disclosed incidents where Chinese planes or ships have taken dangerous and aggressive actions against Australian military assets in international waters in the past 27 months, three of them in the life of the Albanese government.

In each case the Australian air force or navy assets were clearly operating in international waters, in accord with all relevant international norms and laws. However, Inquirer has learned there have been a number of other such incidents that have not been disclosed publicly.

Of the publicly known incidents, in February 2022 a Chinese navy ship aggressively locked a laser on to an Australian P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance aircraft. This is often a precursor to firing on a plane and can blind a pilot. This happened in the Arafura Sea in Australia’s northern approaches. The Australian plane was nearly 8km from the Chinese ship.

On May 26, 2022, just after the Albanese government was elected, a Chinese plane harassed another Australian Poseidon aircraft, also undertaking routine maritime surveillance in international air space in the South China Sea. A Chinese J-16 aircraft pulled alongside the Australian plane and released flares. It then cut directly in front of the Poseidon, very close, and released “chaff”, which is designed to deceive incoming missiles. This chaff contains small pieces of aluminium. Some of these were ingested into the Poseidon’s engine. This is extremely dangerous and could well have resulted in the downing of the Poseidon plane and the death of crew members.

On November 14 last year, Australian divers from HMAS Toowoomba were clearing some underwater lines when a Chinese navy vessel aimed its sonar at them, injuring two Australian sailors. The Toowoomba was inside Japan’s exclusive economic zone and was conducting operations in support of a UN sanctions program against North Korea’s nuclear weapons industry.

Then on May 4 came the most recent incident, with a Chinese J-10 fighter intercepting an Australian Seahawk helicopter, launched from HMAS Hobart, and releasing flares in its path. The Australian pilot was forced into urgent evasive action. There are several ways these flares could have resulted in the downing of the Australian helicopter and potentially the death of the crew.

The Hobart, like the Toowoomba, was also involved in the UN sanctions operations. These UN-authorised patrols don’t seek to interdict international shipping bringing nuclear-related supplies, forbidden under UN resolutions, to North Korea. Rather, they monitor the activities and report them to the UN Security Council.

Unlike the incident with the Toowoomba, which the Albanese government kept secret for some time, within two days Canberra publicly condemned the Chinese action. Both Anthony Albanese and Defence Minister Richard Marles labelled the incident “unprofessional and unsafe”. These seemingly bland terms have a specific meaning within a military context.

As usual, Beijing was contemptuous and dismissive of Australia’s concerns. On this occasion, its explanations for what supposedly happened were not only ridiculous but changed substantially.

In its first response, the Chinese Foreign Ministry claimed the Australian helicopter had flown too close to Chinese territorial waters and the Chinese plane was telling it to move away. This is inconceivable for an Australian ship involved in a UN mission in international waters. It was within China’s exclusive economic zone but that extends 200km from China’s shores. The EEZ, unlike close territorial waters, is available for international maritime traffic to sail through. Nor is there any prohibition on the use of helicopters.

Chinese navy ships routinely operate in other nations’ EEZs. The attack on the Toowoomba divers was undertaken by a Chinese navy vessel within Japan’s EEZ.

On day two China’s Foreign Ministry had a new and even more preposterous story. Now it claimed the Australian helicopter was undertaking a spying mission. Beijing routinely sends intelligence-gathering ships all over the Indo-Pacific, including in many nations’ EEZs.

However, the idea that a noisy, obvious Seahawk helicopter, launched from an Australian air warfare destroyer on a UN sanctions mission, operating lawfully in international waters, was somehow clandestinely engaged in improper spying is ridiculous.

The Chinese Communist Party is an authentically Leninist party, and the Chinese government is Leninist in character and approach. For a Leninist government, truth is purely a function of power. It doesn’t matter what the facts are, what actually happened. What matters is the party’s ability to impose its reality on others. Mostly that’s its own citizens. But in the international sphere it can be any foreign government not strong enough to resist.

Paul Dibb, the grand old man of Australian strategic policy, who dealt extensively with the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War, tells me that in some ways Beijing’s behaviour is more reckless and dangerous than was Cold War Russia’s.

As Campbell points out, Washington has repeatedly sought Beijing’s co-operation in constructing maritime confidence-building and conflict-avoiding mechanisms. At every turn, Beijing flatly refuses to entertain such a project. At a higher level, it also refuses to engage in any arms control negotiations regarding its rapidly growing nuclear weapons arsenal.

“This is worse than the old Soviet Union,” Dibb says. “The Soviets did engage in extensive arms control agreements and there were agreements and protocols to avoid incidents at sea.”

This demonstrates that this dangerous military aggressiveness on Beijing’s part is deliberate and sustained. Sometimes the most loyal pro-China apologists argue, or pretend to argue, that such actions are undertaken by overly aggressive Chinese military field commanders and don’t necessarily represent central Beijing policy. That’s baloney. In the Chinese system the People’s Liberation Army pledges absolute loyalty to the CCP. The party is led with iron command by Xi Jinping. No military commanders are engaging US and allied military assets against the wishes of Xi and the central government.

This is evident in Campbell’s words to Inquirer: “China’s military under President Xi has increasingly been emboldened.”

So three questions emerge: What is Beijing’s purpose in these military actions, what do they mean for Australia, what should we do about them?

Three of the recent Chinese military actions against Australia have taken place since the election of the Albanese government. This means that at the very least the so-called normalisation of relations between Canberra and Beijing has delivered absolutely nothing for Australia on the security front.

It’s actually quite common for Beijing to be both sometimes charming and sometimes insulting and aggressive, trespassing on a nation’s legitimate prerogatives, within the one cycle. The Chinese view is well encapsulated by the words of Yang Jiechi, then Chinese foreign minister, to an ASEAN meeting some years ago: “China is a very large nation, other nations are small nations.”

As a truly Leninist power, Beijing internalises the age-old lesson of power: the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must. Sometimes the strong are in a benevolent mood towards the weak, sometimes not.

Peter Dutton has called on the Prime Minister to “pick up the phone” to Xi and complain directly about this incident. That’s a politically powerful suggestion because it puts the weight on Albanese to show that the much-vaunted new dialogue with Beijing can be activated over serious issues – but it’s obviously unrealistic. Presidents of big nations don’t take phone calls they know are going to be disagreeable or involve complaint.

A decade ago when Tony Abbott as prime minister was dealing with the fallout of ASIS having spied on the wife of the Indonesian president while Kevin Rudd was prime minister, there were many calls for him “to pick up the phone” to Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The truth was Abbott tried to do just that but the Indonesians wouldn’t take the call.

However, there’s no reason Marles, or Foreign Minister Penny Wong shouldn’t try to call their Beijing counterparts over this matter. If the Chinese refuse to take the call, Marles and Wong should publicise that. The Chinese government hates being publicly embarrassed, even when its own conduct is outrageous. Given the power disparities and the importance of the principle, Canberra should take this to a ministerial level. Of course, this risks the whole artifice of dialogue once more crumbling.

In a general sense, it’s a modestly good thing that there should be dialogue at many levels between Canberra and Beijing. But the Chinese have set up a one-way street that works perfectly for them politically but penalises Canberra. The Albanese government’s biggest foreign policy achievement is that it has re-established dialogue with the Chinese government. That means Beijing can destroy the Albanese government’s achievement in a minute simply by suspending or cancelling, or going slow, on the dialogue. That means Canberra is overly incentivised to keep the dialogue going no matter what.

Australian service men and women risk their lives on the high seas in lawful service of their nation. If the Chinese military deliberately puts their lives at risk through illegal, aggressive actions and Australian ministers are too timid to raise these issues directly with their counterparts, then the dialogue, far from being of value, is just another way for Beijing to control Canberra.

Similarly, it’s poor that the Chinese ambassador in Canberra has not been formally called in to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade for a formal diplomatic protest.

In previous years, Australian Labor governments have called in Israeli ambassadors to protest against Israeli settlement policies in the West Bank. Yet the deliberate imperilling of the lives of Australian service personnel apparently doesn’t rise to this level of seriousness.

There’s no need to be naive here. No one should expect any Australian action or protest will change settled policy in Beijing. Bob Carr’s Diary of a Foreign Minister is wonderfully revealing about how little of substance senior Chinese ministers really share with Australian counterparts, and if anything this syndrome has become more severe under Xi’s increasingly repressive regime.

But Beijing must pay some price for its actions. The only price Australia can impose is public protest. And as Campbell points out, we would be speaking and acting with like-minded countries such as the US, Japan, Canada and The Philippines, all of which, among others, have been subject to similar Chinese treatment.

The ultimate purposes of China’s aggressive behaviour are not too mysterious. Beijing has conducted these aggressive and dangerous manoeuvres in the South China Sea, in the East China Sea near Japan, in the Yellow Sea near South Korea and in the Taiwan Strait.

In the Yellow Sea, one consideration is that China is one of the chief countries that routinely breaks the sanctions regime against the North Koreans. But in all four maritime domains Beijing is essentially trying to push out all foreign navies, especially the US and its allies, to claim total control over what are international waters. Unlike Russia, Beijing has not invaded and gone to war with any neighbour. But just like Russia, it is effectively seeking to increase its territorial space and control through military means.

On one land domain, China’s border with India, it acts in a similar fashion.

Nobody knows whether Beijing will attempt to take over Taiwan by force, though it frequently talks of this possibility. More important, for 15 years it has been building a “war economy” and recently has stockpiled huge quantities of essential supply chain ingredients. Military analysts believe the main lesson it’s learning from Russia’s war in Ukraine is that the West lacks staying power.

In the past few days, the Chinese government has issued strict and explicit instructions that all high school and college students are to undergo military training.

Similarly, Beijing’s de facto alliance with Russia, North Korea and Iran means it may well feel emboldened as the US ability to cope simultaneously with multiple crises comes under strain. Beijing likes the shape of things this alliance provides. As US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has argued, Beijing has been Russia’s most important supplier throughout the Ukraine war.

The Albanese government does deserve credit for its willingness to engage in joint missions such as that in the Yellow Sea. However, in these strategic circumstances we should be doing four things: building the biggest and most powerful military we can as quickly as we can; strongly calling out Beijing for aggressive behaviour directly aimed at us; enhancing our alliance with the US; and pursuing as much regional co-operating as possible with nations such as The Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea and India.

The last two, getting close to the US and regional allies, the Albanese government is doing pretty well. On calling out the Chinese, it’s more equivocal. On building a powerful defence force quickly, the performance is very poor. The circumstances surely demand more.

Through its aggressive harassment of US, Australian and other nations’ ships and planes, China is risking a maritime incident that could quickly escalate into serious military conflict, according to US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell.