Australia’s safety in the 1930s depended on the global project. It’s no different now

Once war breaks out, the adversary is in the open; until then, hopes, fears and hesitations blur the sight, cloud the understanding, muddy and obfuscate the debate. That is the situation today.

The 80th anniversary of Allied victory in Europe has recently passed with much commemoration. Less discussed was the decade that led up to World War II – the years WH Auden memorably described as a “low dishonest decade” when “Waves of anger and fear/Circulate over the bright/And darkened lands of the earth”.

Fraught with uncertainties, overshadowed by the seemingly inexorable rise of aggressive, brutally authoritarian regimes, that decade forced the democracies to confront entirely new problems. Their successes were paltry, their failures many. But what is striking is the force with which the dilemmas they faced resonate today.

The difficulties Australian governments grappled with were no exception. At their heart lay the fracturing of the British imperial system.

Whatever the gains from having an empire might have been for Britain, tight integration into “Greater Britain” provided Australia with far-reaching benefits. The country had long relied on free markets for key export industries and ready access to capital from the world’s biggest financial centre. The confusion and rockiness of Britain in the years after the Great War, its shift away from the gold standard in 1931, and the waning of its expansive, free-trade outlook, couldn’t help but impact Australia.

The 1932 Ottawa Agreement had introduced “Imperial Preference”, giving the dominions privileged access to the British market; but it had become increasingly clear that growth opportunities in Britain were extremely limited.

Japan, Australia’s second largest trading partner in the first half of the 1930s, therefore assumed growing importance – raising mounting strategic concerns.

Compounding those issues, Australia’s access to international capital had dwindled. That was not simply because of the global financial crisis; its reputation as a trustworthy borrower had been pummelled. Australian governments, federal but especially state, amassed huge long-term debts during the 20s.

In 1930, as the global crisis was taking its toll, Jim Scullin’s ALP government briefly flirted with delaying debt repayment; soon after, NSW ALP premier Jack Lang announced that interest payments to British bondholders would be suspended. Although the resulting crisis led to Lang’s dismissal by NSW governor Sir Philip Game, Australian governments’ ability to raise new loans virtually disappeared.

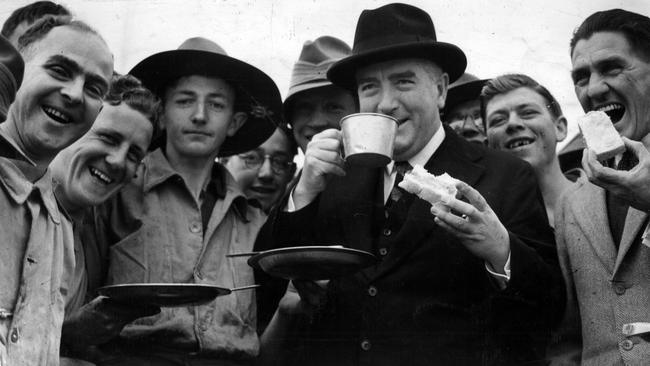

Australia’s position would have been even worse had it not been for Labor renegade Joe Lyons who, filling in as ALP prime minister during Scullin’s absence in late 1930, defied caucus’s demand to effectively repudiate the federal loan repayment. Instead, he led a public campaign to raise the funds by subscription.

Lyons subsequently left the government and the ALP, and formed a new party, the United Australia Party, at the head of the enormous grassroots campaigns that had sprung up in response to Lyons’s privileging of the national interest over party loyalty.

“Honest Joe” deployed his reputation for absolute probity and everyday decency to restore, as best he could, Australia’s creditworthiness, in an ever more fearful, ever more inward-looking world.

But Lyons was particularly ill-equipped to deal with the dangers of a disintegrating world order where predatory authoritarian powers (Imperial Japan, Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany) sought to completely reconstitute the global system. He exhibited in advanced degree both the horror of war that all his generation shared and the pacificism born from the two anti-conscription campaigns.

The mass war graves on the Western Front – which Lyons repeatedly visited on successive trips to Britain – dominated, indeed haunted, his imagination.

He wasn’t alone. Anti-conscription’s legacy of pacificism and antimilitarism permeated the ALP. For the bulk of the interwar period the party opposed close links to Britain for defence.

It also opposed the development of any weapons with offensive capabilities (such as cruisers), insisting that only short-range defence capacity – such as submarines and air force – be developed.

The contradictions at the heart of this attitude were apparent at the time. The ALP’s approach mingled vehement hostility to Britain, the capitalist imperial hegemon, with a naive assumption that Britain’s navy would always ensure that the sea routes on which Australia depended would remain secure. Australia would be protected from invasion by focusing almost entirely on aircraft.

Yet even this policy could be articulated only from opposition. Had the ALP been in government, any increase in defence expenditure would undoubtedly have precipitated a backbench revolt.

It is, as a result, ironic that the nation’s work in rebuilding its defences through the 1930s was driven by two Labor renegades, George Pearce and Billy Hughes, who had left the ALP during the 1916 conscription crisis. While Lyons’s pacifist, anti-militarist instincts ran deep, Pearce and Hughes were hard-headed geo-strategic realists.

Pearce and Hughes were crucial in driving the Lyons government’s commitment to begin rearming, as it did in its 1933-34 estimates. That was before any substantial economic recovery and before Britain belatedly began lifting its defence spending in March 1935. By then, Australian defence expenditure was approaching pre-Depression levels and by 1936 it represented a higher percentage of national income and of federal outlays than in the pre-Depression decade.

Senator Pearce, a carpenter from Western Australia who left school aged 11, served as defence minister under practically every prime minister from Andrew Fisher in 1908 to Lyons in the 1930s. Described by high Tory British prime minister Arthur Balfour as “the greatest natural statesman” he had ever met, Pearce oversaw every major initiative of those decades: establishing Australia’s navy, implementing mass citizen military training before World War I, the Great War itself, the ambitious post-conflict demobilisation scheme in co-ordination with General John Monash, designing the nation’s post-war defence scheme in the 20s and then engineering defence renewal in the 30s.

As for Hughes, Australia’s pocket rocket prime minister in the Great War, the role he played in the period was similar to Winston Churchill’s: completely immune to the allure of disarmament that gripped the political classes and general population, he repeatedly warned of the rapidly worsening military risks. Claims that he was a warmonger past his use-by-date did nothing to deter him from what he saw as his duty.

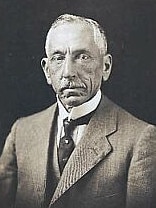

Hughes, Pearce and (after the latter’s 1934 political exit) his replacement as defence minister, Archdale Parkhill, were continuing a basic geostrategic awareness that traced back to the global strategic vision of Alfred Deakin.

Deakin returned from the first Imperial Conference in 1887, which had focused largely on defence and Pacific security questions, describing the “armed camps” that European nations had become. Faced with the threats that posed, he argued that school students should be given compulsory military training – a measure introduced shortly after Federation.

It was Deakin, too, who initiated the Royal Australian Navy as an independent national fleet. In 1907 he made the fundamental observation that still captures the totality of Australia’s strategic existence: “Shut off access by sea to Australia and the whole nation stops.”

Pearce echoed this in 1933 when he pointed out: “If Australian markets were closed and her imports and exports stopped by enemy action, she could be forced to sue for peace without a single enemy soldier coming within sight of her shores.”

What Deakin, Pearce and Parkhill understood was that Australia’s safety and independence depended on the success of a wider global project: a globalism, built out of free passage across the open seas of the world, which Australia had enjoyed for the entirety of its post-1788 existence thanks solely to the Pax Britannica.

The sense of vulnerability that dependence created took on new focus when Japan invaded Chinese Manchuria in 1931. Despite crippling fiscal constraints, Japan’s renewed aggressiveness helped convince the Lyons government to seriously shift the dial on defence spending so far in advance of Britain itself. As for the Admiralty’s assurances about the solidity of the new Singapore fortress that the British had built slowly and reluctantly, they didn’t persuade successive Australian leaders.

At the 1937 Imperial Conference Australia was the only dominion to actively probe the question of imperial defence systems and insist on more detailed planning. But the irreducible problem remained. Although Britain still had the largest and most powerful navy in the world in every class of ship, the days when it could comfortably outmatch the next two largest navies in the world combined had gone forever.

Rather, Britain’s one great fleet now had a two-ocean dilemma. As the First Sea Lord had warned in April 1931: “The number of (our) capital ships is so reduced that should the protection of our interests render it necessary to move our Fleet to the East, insufficient vessels of this type could be left in Home waters to insure the security of our trade and territory in the event of any dispute arising with a European Power.”

The security predicament was exacerbated by a dilemma with which today’s readers will be all too familiar. Britain, the country’s security guarantor, was increasingly estranged from Australia’s second largest (and still growing) trading partner, Japan – which was also our greatest military threat in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Lyons government’s Trade Diversion Policy of 1936, which sought to redirect trade elsewhere, prioritised security over immediate economic gain; but it was loudly criticised by the Australian stakeholders most directly affected, notably the graziers, and in any event seemed ineffective.

In short, Australian governments faced a perfect storm. The global system from which Australia had derived such immense benefits was visibly collapsing. Taking its place was a fragmented world in which the ability of our most powerful friend to protect this country’s vital interests was being seriously challenged. And a terrible choice had to be made between trade and security, between immediate and deeply unpopular economic pain on the one hand and strengthening Australia’s most formidable adversary on the other.

All this was entirely novel, depriving the nation’s leaders of any usable past on which to draw. As Churchill described it when reflecting on the dilemmas with which Britain was then grappling: “The compass has been damaged; the charts are out of date.”

An important part of the answer was thought to lie in appeasement, which was not yet a pejorative term. It was, on the contrary, well within what we could now call the playbook of the Anglosphere’s elites: since at least the middle of the 19th century, British leaders had relied on coming to terms with adversaries they could not afford to fight.

As Paul Kennedy concluded in his study of British foreign policy, those elites had a long-established preference for “settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and compromise”. They had, for example, neutralised threats from France and Russia before World War I by making deals over colonial territory. Now they were trying to apply the same conciliatory approach to Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

In the lead-up to the 1937 Imperial Conference Australia was therefore cabling Britain urging more be done to better relations with Japan, perhaps along the lines of the recent Anglo-Italian Pact. The nearly 20 papers issued to Australian conference participants by External Affairs, recently established as a stand-alone department, described the public campaign in Japan for a “southward advance” policy of imperial expansion, with all the dangers that created for Australia. But mindful of the fiscal constraints on Australian rearmament and noting that the US remained “at heart isolationist”, the department advocated rapprochement with Japan, if only to buy time before a seemingly inevitable conflict.

That was paralleled by an effort to extend Australia’s alliances. The dispatch in 1939 by the new Menzies government of Richard Casey to represent for the first time distinctively Australian interests in Washington was especially important. Accompanying it was a broad range of initiatives aimed at eliciting a firm American commitment to Asia-Pacific security.

Those initiatives bore fruit at the end of November 1941 when the Roosevelt administration indicated it would commit armed forces to defend the Asia-Pacific beyond its own immediate territorial interests. Franklin Roosevelt’s chief foreign policy adviser, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, confided to Casey that “we cannot allow ourselves to be cut off from essential defence needs”, nor could the US let itself be reduced to “the position of asking Japanese permission to trade in the Pacific”.

The significance of this commitment didn’t take long to become apparent – a few days later, Japan launched the Pacific War, pre-emptively attacking, among other strategic positions, Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

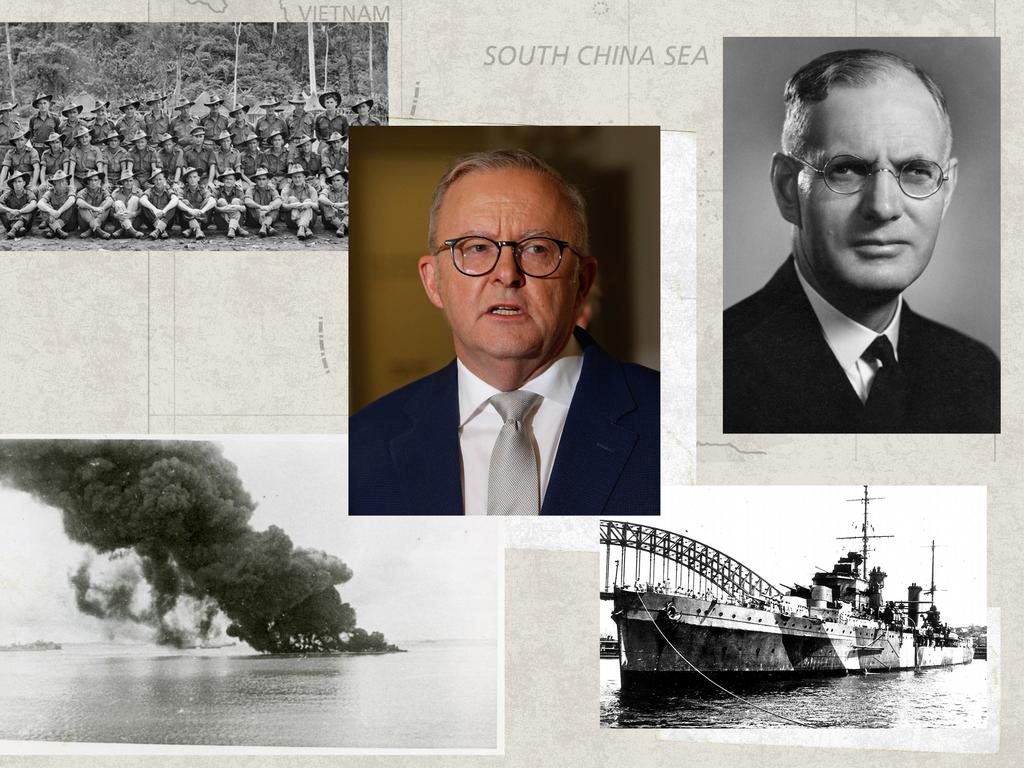

That hard-won American pledge is the essential context for understanding John Curtin’s actions as prime minister. Despite his own claims and Labor’s never-ending hagiography, the reality is that Curtin benefited enormously from the fact his party had been nowhere near power nor forced to take the critical decisions in the lead-up to war. Crucial heavy lifting on Australia’s war-waging capacity and global alliance-building was done by his predecessors; largely eliminated from subsequent political narratives, they provided the basis for what Curtin achieved.

Honae Cuffe is therefore right to conclude, in her impressive study of the formation of Australia’s Asia-Pacific policy, that as the global outlook darkened, trade, diplomacy and defence were all pursued in an attempt to secure and maintain Australia’s sovereignty.

Yes, there were errors of appreciation, including Robert Menzies’ excessive faith in what appeasing Germany might achieve – though Menzies was immeasurably more cautious in that respect than the leadership of the ALP. But despite those shortcomings (which were hardly Australia’s alone), the period saw, as Cuffe writes, “the emergence of a lucid and opportunistic foreign policy in which policymakers carefully assessed international developments, the strategies of the great powers and the opportunities available to project the national interest”.

All that was preparatory to an existential confrontation with the real choices of national existence, choices we had largely managed to avoid before the full onset of the Pacific War. It was this conflict, Paul Hasluck wrote in the war’s immediate aftermath, that signalled the moment Australia “came to understand in more brutal terms what its claim to nationhood meant and to meet the stark and single issue of survival”.

The bedrock problem in meeting that challenge was this: Australia did not just have to depend on its allies for their military strength. However clear-sighted or misty-eyed our perceptions of the situation might be, we were also dependent on the acuity and coherence of our allies’ strategic vision.

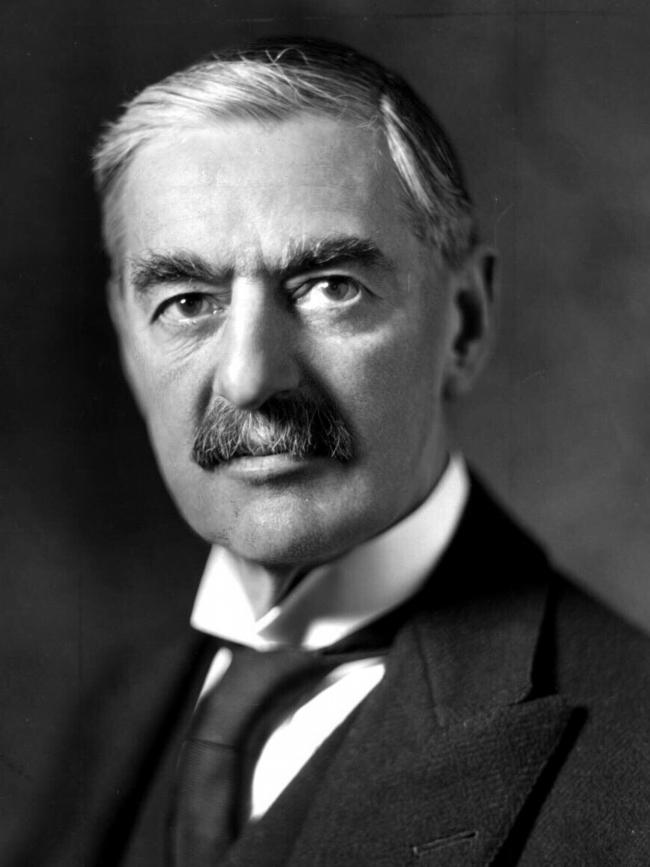

British prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s weaknesses in that respect are well-known, as are those of his closest advisers. Historians’ recent attempts to cast him more favourably than did the post-war consensus are not entirely groundless. But they cannot erase the fact he continued to believe, even when every illusion should have been shattered, that Hitler “was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word”.

Concessions, Chamberlain thought, would strengthen the hands of “political moderates” in Germany. Indeed, Eric Phipps, Britain’s ambassador to Germany from 1933 to 1936, suggested that Hitler was one of them, while his successor, Nevile Henderson, was convinced Hermann Goering’s passion for hunting and fishing, which gave him some kinship with the English aristocracy, meant he would naturally tone down Hitler’s aggressiveness.

That belief, that even brutally authoritarian regimes could be tempered by “moderates”, was one of the period’s most disastrous convictions. Cabinet discussions were replete with fatuous comparisons to Louis XIV or Napoleon. Faced time and again with those claims, Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London, could hardly be blamed for concluding that “English gentlemen” (meaning Chamberlain and his coterie) suffered from a “complete failure to grasp the psychology of such men as Hitler and Mussolini” – and even more so to grasp what was new and terrifying about them.

No matter how ill-judged Chamberlain’s views may have been, they resonated with a public that dreaded nothing more than another war. In 1933, a Labour candidate won a by-election for the eminently safe Conservative seat of Fulham East by campaigning entirely on a pacifist platform.

Four years later Chamberlain’s predecessor as British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, who considered that defeat a political earthquake, still felt “a stronger pacifist feeling running through this country than at any time since the War” – making far-reaching rearmament politically impossible.

Roosevelt’s vision was much clearer than Chamberlain’s. He was, however, far more tightly hemmed in.

“The epidemic of world lawlessness is spreading,” he warned in 1937. Americans should not imagine that “this Western Hemisphere will not be attacked and that it will continue tranquilly and peacefully to carry on the ethics and the arts of civilisation”.

However, a Gallup poll gauging the public reaction to his speech found that 60 per cent of voters wanted congress to pass even more stringent measures barring US involvement in a new war.

Stung by the resulting congressional blowback, Roosevelt bitterly complained to his speechwriter: “It’s a terrible thing to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead – and find no one there.”

Of course, none of that stopped Roosevelt, who redoubled his efforts after Munich: “There can be no peace,” he said, in a radio address immediately after Hitler got his way, “if the reign of law is replaced by a recurrent sanctification of sheer force.”

Equally, Hughes warned a uniformly hostile House of Representatives that Chamberlain’s Munich deal, which had been met in Australia, as elsewhere, with unanimous jubilation, actually changed nothing: “The danger is still there. In a little while the clouds will gather again.”

And more than anyone else Churchill remorselessly continued the fight against the defeatists, eventually toppling Chamberlain.

Unfortunately, by the time Churchill and Roosevelt were firmly in control the opportunity to readily stem the dictators had been squandered – and millions of lives that could have been saved were gone with it.

It would be all too easy to draw from the 30s an isolationist conclusion. After all, it was obvious that Britain’s naval predominance was waning. Given that, shouldn’t Australia have built an infinitude of aircraft to defend the immediate shoreline? But as satisfying as it might feel, then as now, to focus solely on territorial defence, that is little better than an elaborate exercise in reality denial.

The real lesson, which Menzies, Hasluck and others showed in their subsequent decades’ overview of Australian defence, is that Australia’s defence inevitably lies in the world. As Australia can be cut off and defeated without an enemy touching the coastline, so too must the defence be forward. And that defence is only feasible if it is conducted in vigorous alliance with others.

To expect those alliances to be easy to maintain or always harmonious would be foolish. Allies’ interests – and, no less ominously, their perceptions – differ and we lack the sway to impose our own. Strategists talk of the “fog of war”; but few fogs are thicker than the fog of peace, when the shape of future conflicts is wrapped in the mists, creating uncertainties about when, where and how they will unfold. Once war breaks out, the adversary is in the open; until then, hopes, fears and hesitations blur the sight, cloud the understanding, muddy and obfuscate the debate.

That is the situation today. With a recently released report decrying our “paper ADF”, we seem to be witnessing, as Auden did so many years ago, “the clever hopes expire” midway through our own “low, dishonest decade”. Whether our leaders have the vision to recognise and the courage to confront that grim reality will determine our future.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout