Australia’s relations with China reach peak panda as Premier Li Qiang flies into Adelaide

For all the trade success and bonhomie at Adelaide Zoo, there is unease about what comes after the visit by Xi Jinping’s deputy. Others in Canberra say this is the sweetspot.

Have more hours ever been spent planning a trip to Australia? China already takes up more of the Australian government’s time than any other country. In the lead-up to these rare visits by Chinese leaders, the tally of human hours grows even longer as dates are canvassed, the agenda fastidiously curated and the Australian Federal Police erects barricades to separate “patriotic” Chinese from human rights protesters outside Parliament House.

In the telling of Australian officials involved in the six months of diplomatic negotiations that have preceded Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s trip, it has been worth the effort. Beijing has been keener than Canberra in the negotiations, giving ground on Australia’s key demands – above all, removing the remaining products from the trade blacklist that has been enforced by Chinese customs since 2020.

“It’s a good place to be,” one senior Australian official says.

Australia, in this assessment, is getting what we want without changing any of our core positions. Canberra’s rebuffing of Beijing’s request for the Royal Australian Navy to resume training exercises with their counterparts in the People’s Liberation Army Navy, for example, hasn’t stalled things (although, less reassuringly, our two militaries continue to have engagements of a different nature in the South and East China seas).

This, apparently, is the sweet spot for Australia’s relationship with China in the second decade of Xi Jinping’s reign: the trade access of the pre-2018 era, but with much firmer security settings as the Albanese government continues and builds on Turnbull and Morrison era policies.

Across the next four days, the government wants to underscore the real-world benefits of this approach, particularly in South Australia and Western Australia, key states in the next federal election and both stops on the Li’s trip.

Giant pandas, on loan from Beijing for $1m a year, are to keep munching bamboo at Adelaide Zoo. China’s second most senior leader will toast with Australian wine, welcome promotion for the pummelled industry. Our lobsters likely will soon be allowed to be sold legally in China rather than being smuggled in by criminal syndicates in Hong Kong. The positive press in Chinese media should help tourism.

For all the trade success, there is discernible unease in pockets of the Australian system about what comes next. Anthony Albanese is alert to that criticism. The Prime Minister addressed it in a commentary piece published in The Australian on Wednesday.

“Through two years of engaging in Australia’s national interest, our government has never sought stabilisation for its own sake, or at any price,” Albanese wrote. “This is not always a smooth process, or a swift one, but while issuing threats and delivering ultimatums may be the easy road, it never takes you very far.”

The government says it aims to express Australia’s concerns but in a way that isn’t counter-productive. “Our objective is to not get the phone slammed down,” explains one of the Prime Minister’s top officials.

Some worry about a creeping overeagerness to mute discord and stress the positive in a relationship that, despite tangible improvements, remains riven with deep, structural problems. After the most harrowing period in Australia’s 52-year official relationship with the People’s Republic of China, some participants say they see something approaching post-traumatic stress disorder among certain colleagues.

There is concern the trade and diplomatic successes may be convincing some to aspire to a more ambitious era of “normalised” relations, despite ample evidence that Australia’s relationship with China remains blazingly abnormal. Comments a few months ago from Trade Minister Don Farrell raised eyebrows.

“Just because we’re doing $300bn worth of two-way trade at the moment doesn’t mean that figure can’t be $400bn,” Farrell said.

“What about the need to diversify?” one official grumbled. “Isn’t that the policy?”

What does China want?

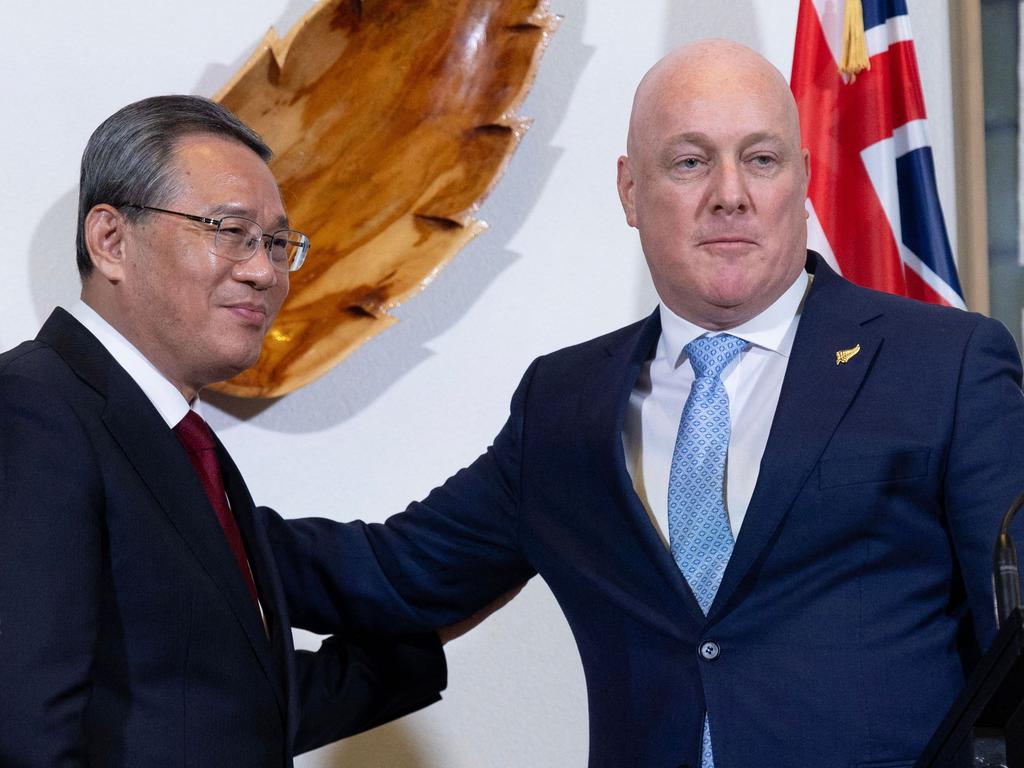

For all the imminent panda bonhomie, Australia remains China’s Tasman troublemaker, while New Zealand, from Beijing’s point of view, has been much better behaved. Announcing the Chinese Premier’s trip to Wellington, a spokesman in Beijing said: “China and New Zealand are each other’s important co-operation partners.” The same foreign ministry spokesman said: “China and Australia are both important countries … with high economic complementarity and a promising future for co-operation.”

The omission of the word partner and the stress on the potential of the relationship underscores Beijing’s assessment that Australia remains a work in progress, according to Diane Hu, deputy director at Beijing Foreign Studies University’s Australian Studies Centre. She says Beijing’s top priorities for the trip are continuing to “stabilise” the relationship and to find “fruitful” areas of co-operation. Top of the co-operation list are clean energy and resource partnerships, which China needs for its future-facing industries. It’s why during the Perth leg of his trip Li will visit Chinese company Tianqi’s lithium venture and a hydrogen project being developed by Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue.

While this visit has been making headlines for months in Australia, the coverage has been more modest in Chinese media. That’s no surprise when you consider the world from the perspective of China, which has land borders with 14 countries, four of them nuclear armed, and maritime disputes with another half-dozen states. Its east coast is flanked by US military bases.

“China has a lot more countries to worry about,” Hu says.

Australia, by contrast, can sometimes seem to be suffering from China monomania, one reason China has been so confused by our behaviour since the previous Chinese premier’s visit.

Another is the clustering of Australia (and New Zealand) within the North America and Oceania desk in the Chinese foreign ministry. “I think that’s why a lot of the things about Australia have been seen through the US lens in China,” Hu says.

In their closed-door discussions, Li will focus that US lens on Albanese as he again urges Australia to temper its “Cold War mentality” and stop joining American-led “small circles”, such as AUKUS and the Quad.

Chen Hong, director of Australia and New Zealand studies at Shanghai’s East China Normal University, has a simpler explanation for the relationship’s troubles: Scott Morrison. It’s the orthodox view among Chinese officials, many of whom couldn’t restrain their laughter when the former prime minister revealed he was prescribed medication in 2020 to cope with debilitating anxiety. In their view, that explained a lot.

Chen applauds the bilateral formula of the Albanese government: co-operate where we can, disagree where we must. “China does that too,” he tells Inquirer.

The Shanghai-based professor, who once translated for Bob Hawke and is a frequent commentator for China’s pugnacious Global Times, was personally engulfed in the bilateral rupture. Back in 2016 when then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull addressed a huge business delegation in Shanghai for Australia Week in China, Chen was in the audience.

By 2020, Chen had a visa application blocked by ASIO, which said he posed a security risk. An attempt to gain a visitor’s visa to Australia last year went unanswered – a small example of the continuity of China policy from the Turnbull-Morrison years. New Zealand’s government takes a different view. Chen travelled there earlier this month in the lead-up to this week’s visit by Li to Wellington.

Towards a messy ‘settling point’

When the previous Chinese premier visited Australia, Turnbull brought up the dragon in the room. “Surely China should want to be seen as more of a cuddly panda than a scary dragon? Your growing strength makes people anxious,” Australia’s prime minister said over dinner.

As people in The Philippines, India, Canada, Hong Kong or Taiwan could attest, China’s leadership was not persuaded. Beijing’s actions since then have precipitated a collapse in Australian public sentiment towards China. Back in 2017, more than 50 per cent of Australians told the Lowy Institute they trusted China. Seven years on, that has plunged to 17 per cent. Only Vladimir Putin’s bloodstained Russia scored worse.

A separate poll released by University of Technology Sydney’s Australia-China Relations Institute this week confirmed the findings. On question after question, Australians gave answers that Chinese diplomats will want to keep well away from their visiting comrade. A clear majority opposes the lease of the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company. We don’t want China in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Trade. We think Australia is too exposed to the Chinese economy. We fear Australia could end up in a military conflict with China, perhaps even in the next three years.

And, according to UTS’s ACRI poll, the number of Australians who say Labor is best placed to handle relations with China shrank in the last year. Labor remains ahead of the Coalition, but the margin is much tighter than Chinese officials would like.

Beijing blames the collapse of Australian sentiment on the media, not China’s actions. “Those polls are largely influenced by the media,” one Chinese counterpart told me.

Australian diplomats are told the same line. “I don’t know that China is very self-aware,” one observes, dryly. China’s diagnosis leaves its officials speaking as if they have no agency. “China can do nothing,” they lament.

A more accurate assessment is that China won’t do anything of significance to address the straining fault lines in the relationship beyond restoring trade access for goods it blocked in 2020. That doesn’t mean the relationship will necessarily collapse but it does put a very low ceiling over it.

Ben Herscovitch, a close watcher of the bilateral relationship, says Li’s visit to Australia will mark a “settling point” with China. It will be messy, Herscovitch says, with “a new flare-up or the re-emergence of an old (one)” shaking up relations regularly, perhaps frequently.

“When Australian vessels are in the South China Sea or when Australian parliamentarians go to Taiwan or when Australian diaspora communities are living their lives, there will still be all sorts of instances where Beijing is trying to exert pressure and punish and push, and that will cause periodic murmuring and tensions in the relationship,” says Herscovitch, a research fellow at the Australian National University and author of the Beijing to Canberra and Back newsletter.

Sustaining even this modest settling point will require tremendous effort. “It will be a matter of deftness and skill in both Canberra and Beijing to manage all of those many, and probably growing, points of disagreement,” Herscovitch says.

If it holds until the next visit by a Chinese premier, it will be another surprise in Australia’s headache-inducing, but never boring, relationship with China.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout