Australian vaccination rates – and trust – slide after Covid

Alarm is being raised as routine vaccination rates fall in the pandemic’s wake, posing a threat to us all | Rates of undervaccinated babies vary across the nation.

Leading epidemiologist Raina MacIntyre was in a hospital emergency ward late in 2024 when she overheard a conversation that left her dumbfounded. “I thought, oh my goodness, is this how bad things are?”

The man in the next cubicle had suffered an animal bite and his doctor recommended a tetanus booster, a routine and uncontroversial suggestion that nonetheless alarmed the patient. “I don’t want it. I’m not having it,” he insisted. “I know 30 people who dropped dead.”

“Dropped dead from what?” the doctor asked.

“You know, Covid vaccines,” he replied.

The doctor didn’t counter his argument, discuss his concerns or explain that serious side effects are rare and benefits are proven. Instead, the busy medico gave him the antibiotics he demanded and let the matter slide.

MacIntyre, a professor of global biosecurity who has worked in vaccines since the early 1990s, sighs down the phone. Covid has become such a toxic topic that even doctors are reluctant to push back, she says.

She tells the emergency-ward story because it is emblematic of a serious multi-pronged hangover from the Covid pandemic: an erosion of trust in health advice and a surge in unchecked vaccine misinformation that are having serious real-world consequences.

Vaccination rates are falling and anti-vaccination propaganda is rising, and if it continues we risk losing the phenomenal gains to human health from the elimination and control of serious infections, MacIntyre says.

It’s a global issue but alarm bells are already ringing in Australia, where there has been a drop in immunisation rates in children and adolescents and a slide in influenza and shingles jabs in adults.

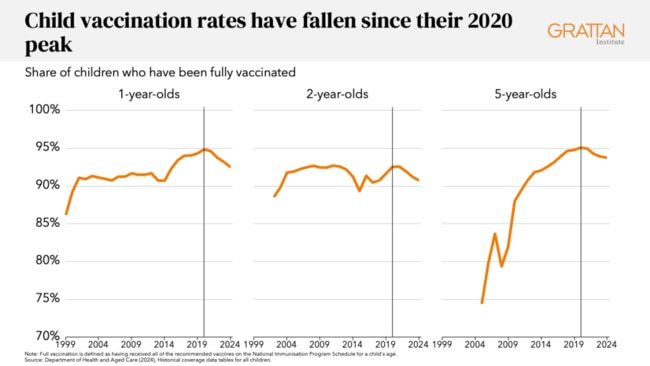

For years before Covid, Australia’s childhood vaccination rates were gold standard by global measures, hitting a peak in 2020 close to the 95 per cent target.

Since then they have dropped each year for every recommended child vaccine across every age group. Indigenous children have lower coverage than the rest of the population for almost every vaccine.

Latest figures from the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance show the rate of fully vaccinated 12-month-olds fell to 92.8 per cent in 2023 from 94.8 per cent in 2020, while two-year-olds slipped to 90.8 per cent from 92.1 per cent in the same period.

And it’s not just children – one in four 18-year-olds hasn’t received their three recommended vaccines (human papillomavirus, the combined diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine and meningococcal).

The Covid-19 Response Inquiry Report handed down late in 2024 highlighted the need for a national strategy to improve vaccination rates and rebuild community trust in vaccines, and Health Minister Mark Butler warned of 7 per cent to 8 per cent declines in under-fives vaccinated against measles and whooping cough.

In the coastal Richmond Valley in the NSW Northern Rivers region, for example, one in five two-year-olds isn’t vaccinated against measles and in the Dural-Wiseman’s Ferry area northwest of Sydney about 15 per cent aren’t protected. In the Gold Coast hinterland, just 79 per cent of two-year-olds have had the jab.

“That means we are now well below herd immunity levels for those two really important diseases,’’ Butler said of the general decline in coverage.

“This isn’t just about the pandemic response. This is bleeding into a whole bunch of really important health programs.”

His warning came as Australia logged a record 54,000 whooping cough cases, also known as pertussis, in 2024, a trend that has continued into 2025 with almost 5000 cases, an unusually high number, recorded in January. The infection is particularly dangerous for babies and in November 2024 a two-month-old died from whooping cough in Queensland.

Measles already has been reported in Australia in 2025, linked to travellers returning from Southeast Asia where Vietnam and Thailand are experiencing alarming spikes in cases.

In the US, health officials are watching escalating measles outbreaks – particularly in New Mexico and Texas – that have killed an unvaccinated child and adult and hospitalised many more as reports emerge of patients shunning conventional treatment and seeking unproven remedies such as cod liver oil.

The elevation of vaccine sceptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr to US health secretary has further worried health experts and emboldened hardcore anti-vaccination groups that bombard social media channels with messages that drip into the feeds of anxious parents.

Grattan Institute health program director Peter Breadon says the small but sustained overall downturn in immunisation since the pandemic does not appear to be a blip.

“I think it is a real change in direction. For every year, for every vaccine on the child immunisation program, we’ve seen declines (since 2020). Throughout the history of mass child immunisation in Australia, over the past quarter century, we haven’t seen this kind of broad or sustained a downturn,” he says.

“It’s happening in other countries, too, with that same inflection point of 2020, and this suggests to me that something has changed.”

The problem in Australia is not restricted to geographic areas long known to have pockets of vaccine resistance.

In 2020, Breadon says, Australia had 11 communities where more than 10 per cent of one-year-old children were not fully vaccinated. In 2024 that blew out to 53 regions, leaving more areas more vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

Grattan Institute analysis shows that areas with vaccination rates close to 95 per cent for one-year-olds in 2020 such as Barkly north of Alice Springs, Clarence Valley in northern NSW and Macedon Ranges in Victoria have all slumped into the 80s by September 2024.

Breadon says several factors could be at play: routine healthcare was disrupted during the pandemic and parents are still reporting difficulty getting a doctor’s appointment. In a cost-of-living crisis they are worried about costs if they can’t find a bulk-billing doctor.

Support for vaccines also has faltered. One Australian report commissioned by the Health Department in 2022 found the proportion of parents of under-fives who strongly supported childhood vaccination dropped from 72 per cent in 2017 to 50 per cent in 2022.

NCIRS associate director surveillance, coverage, evaluation and social science Frank Beard says although the overall decline in childhood immunisation is modest, the ongoing downward trend is concerning. Further work is under way to find the root cause, and early results confirm a double whammy of accessibility to immunisation services and acceptance of vaccines.

The National Vaccination Insights project, a collaboration of social science researchers, surveyed 2000 parents in 2024 to understand the drivers behind vaccination decisions for children aged under five.

The survey group consisted of parents whose children were up to date, partially vaccinated and unvaccinated.

NCIRS research fellow Maryke Steffens says the practicalities of accessing a vaccination service is an issue. About one in 10 parents reported difficulties getting medical appointments and worries about cost.

Parents of up-to-date children were more accepting of vaccines and parents of unvaccinated children more sceptical – almost half of parents in this category had concerns about vaccine safety and four in 10 questioned their effectiveness.

The partially vaccinated cohort also reported significant access barriers, but 17.7 per cent said they did not believe vaccines were safe for a child and 16 per cent said they would not feel guilty if their child got a vaccine-preventable disease and did not trust the information about vaccines delivered by their doctor or nurse.

It is this cohort that authorities want to target. The research will be used to tailor programs to improve access and ensure medicos are equipped to answer patient questions. Steffens says that in interviews after the survey parents wanted more information about the risks and benefits of vaccination and the risk of the disease itself.

“But the problem is people didn’t feel like they had enough time with healthcare providers to really talk about these two concerns and to have their questions answered adequately, so that’s an issue,” Steffens says.

Hardcore vaccine refusers are difficult to reach and MacIntyre, who heads the biosecurity program at the Kirby Institute, refers to research that suggests there is not much point trying to change their minds.

An important issue now, she says, it to ensure these fringe beliefs don’t become mainstream.

West Australian mum and immunisation campaigner Catherine Hughes noticed a distinct change in public sentiment during the Covid pandemic.

Hughes has been at the forefront of advocacy since 2016 after she and husband Greg lost their healthy baby son Riley to whooping cough a year earlier.

Too young to be vaccinated, Riley was only 32 days old when he died in his parents’ arms, a life-altering tragedy that sent Catherine Hughes on a mission to raise awareness of the importance of immunisation. She wants parents who are wavering or putting off vaccination to read of Riley’s last conscious hours: “He was screaming and screaming as they got him ready for life support …”

Her Light for Riley social media pages and the Hughes family’s Immunisation Foundation of Australia website are calm and measured sources of information and stories from other parents who had close calls or lost children who were too young to be vaccinated. The IFA works to be a bridge between the community and scientific research, and Hughes keeps close tabs on disease outbreaks and vaccination data.

Before 2020, she says, the community was highly accepting of immunisation. “And then we had Covid and I think what has happened since then has been a drop in confidence in immunisation and a drop in trust of healthcare providers and in government and pharmaceutical companies. Now we are seeing a decline in immunisation rates as a result of this loss of confidence.

“It’s not quite panic stations yet, but if this trend continues we are in trouble.”

Hughes’s advocacy spurred Australian authorities to introduce whooping cough vaccination during pregnancy to protect newborns and more recently she has been instrumental in having respiratory syncytial virus added in 2025 to the National Immunisation Program for women at 28 to 36 weeks of pregnancy.

Now she says her group will focus on pushing for equitable access to vaccines and helping to restore vaccine confidence.

“The government has done a wonderful job in the funding of vaccines, but I definitely think we need to address the acceptance issue and fund more campaigns and education that will help communities have trust in vaccination,” Hughes says.

The federal government is working on a new five-year National Immunisation Strategy to improve coverage, prepare for new diseases, strengthen community engagement and build trust in vaccines.

This loss of the confidence, which also has hit other wealthy countries such as the US, Britain and New Zealand, has been described as the great paradox of the Covid pandemic.

“One of the most successful innovations in public health history, the rapid development of Covid vaccines, has actually had the effect of reducing public confidence in vaccination,” Swansea University public health researcher Simon Williams told the BBC in January.

Pinpointing why this happened has proven more difficult.

Hughes suspects vaccine mandates had a role to play.

“I understand the importance of mandates in helping to protect us from Covid and being hospitalised with a disease that took the lives of many people, but I think it damaged trust between certain communities and government,” Hughes says.

“As these mandates were implemented we saw a rise, particularly online, in anti-vaccine activism and aggression towards people who were advocating for vaccines.’’

MacIntyre, who has written a soon-to-be-released book, Vaccine Nation, says she believes hardline measures such as lockdowns and restrictions became conflated with public health measures. “The pandemic has been extremely triggering for almost everybody in different ways … and I think a lot of people were just angry, and they conflated all public health measures, including vaccines, with all sorts of control and coercion.”

Others became genuinely confused about the vaccination rollout in the face of inconsistent and changing advice and the emergence of rare but serious side effects of the AstraZeneca vaccine and increased incidence of the heart conditions myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA vaccination. Some felt their concerns and questions about the vaccines were casually dismissed and acknowledgment of side effects muted as authorities rushed to lift immunisation rates.

The Covid-19 Response Inquiry Report acknowledged the problem: “The communication challenges around vaccines were significant, and the government’s approach added confusion to what is already a complicated topic.

“This pandemic legacy of a loss of trust in vaccines within an active and entrenched vaccine misinformation and disinformation environment is having a continued effect on Australian vaccination rates, including Covid-19 boosters and non-Covid-19 vaccines.”

It said misinformation and disinformation needed to be actively addressed and on this point MacIntyre enthusiastically agrees, accusing her own profession and the government of vacating the space. Anti-vaccine propaganda must be countered at every turn, she says.

MacIntyre returns to her experience in the emergency ward overhearing a patient confusing tetanus and Covid vaccines.

If she were his treating doctor, what would she have done?

“I would have said I am really sorry his friends passed away and asked what happened, because if you let people talk and express their concerns, often that gives a clue as to what the issues are.

“I would have explained that it’s highly unlikely that Covid vaccines caused the deaths of his friends and I would have told him about the huge safety studies.”

She would have explained that there had been 14 documented deaths linked with Covid vaccines across Australia, where more than 60 million doses have been administered. Thirteen of those deaths were linked with the discontinued Astra Zeneca jab and none involved children.

There’s a simple line in her book that could help persuade the doubters. In the pre-vaccine era, infectious diseases were the leading cause of deaths in children. In most countries today, more than 99 per cent of children survive to adulthood. “When we live with the vast gains achieved by public health and vaccination we can’t take these gains for granted,” MacIntyre says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout