Australia is a thorn in Xi Jinping’s side, not mere gum on his shoe

Beijing — which has brought Tibet, Xinjiang and now Hong Kong to heel — needs to ensure that Australia defers to it appropriately. We are now a thorn in Xi Jinping’s side, not mere gum on his shoe.

China can’t afford to let Australia “get away with” whatever acts or words it views as injurious. Nor can Australia afford to be seen by the rest of the world — which is by now watching avidly — to cave in.

So the chances of a reset, or a reboot, are slim before the international scene settles into separate hubs of influence, of tech platforms, of infrastructure, of trade, and of security arrangements — one with its spokes emanating from Washington, and the other with its Belt and Road Initiative spokes centred on Beijing.

Xi Jinping was assured of ascending to China’s top job eight years ago by the fortuitous fall of his bitter rival Bo Xilai, who was swiftly jailed for life. Xi has not stopped climbing since.

Former Australian ambassador to China Geoff Raby describes the circumstances of his succession as a return to Leninism. There is a sense about Xi’s China that if he, or it, pauses to survey the scene or to savour the moment, they fear losing their balance and plunging back down.

Xi rapidly purged the communist party that has ruled China for 71 years, satisfying thereby the party’s veteran leaders, who had become convinced that it had become so sclerotically corrupt that it needed a heart transplant.

China’s new, purified heart beats only to the new leader’s drum. Loyalty to Xi is the core requirement for serious promotion.

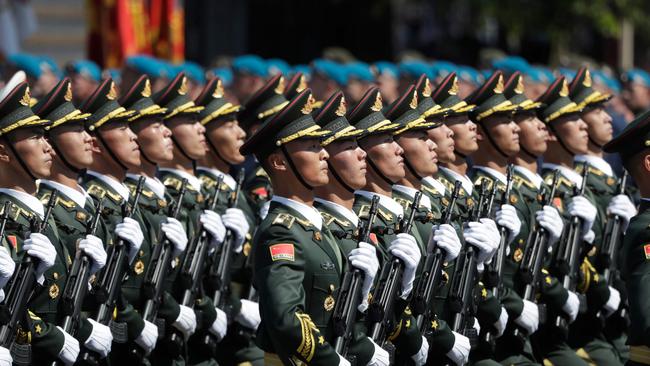

Australia has been hearing that martial beat loud and clear in recent times. This past week, deafeningly so.

Once Xi had grappled down his residual rivals and competing factions, his Thought on Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for a New Era was enshrined in party and state constitutions, with the stress on this being a new era.

This is an era in which China’s rulers feel that it now has enough economic heft, enough military might, enough ultra-modern infrastructure, and enough robust institutions — all directed by the party with its clear line of command — to go it alone.

Many of China’s middle class who were until COVID-19’s rude interruption travelling overseas for holidays, for business or for studies, returned with a similar thought — our world is better run, our system is superior.

The endless speculation in the US and the rest of the West about whether China preferred Donald Trump or Joe Biden missed the point. Beijing simply shrugged. It felt it didn’t really matter, since its future was now in its own hands.

Nevertheless, lacking electoral legitimation, the party — for all its relentless bravado — wants assurance that it is maintaining popular support, and thus it also seeks ways to display that it retains the mandate of heaven, the ordained right to rule.

Since Mao Zedong died 44 years ago, constantly rising prosperity has underwritten that crucial form of legitimacy. Now, however, signs are emerging that China’s economy is set to revert, over time, to the global mean.

Xi faces massive fresh challenges on that economic front, which is a new battleground for him — and many experts believe that they cannot be resolved by his continuing to place politics in front of every other priority, especially when economic reforms are long overdue.

So a fresh source of popular legitimation is also required. Xi has set on “going out” — regional dominance and global influence and respect — as the answer.

This triggered a cultural revolution within China’s ministry of foreign affairs to make it fit for this new purpose. The minister, Wang Yi, told a gathering of 1000 diplomats at the celebration of the ministry’s 70th anniversary a year ago that they should now imbibe a “fighting spirit”.

The huge box office success in China of the Rambo-style film Wolf Warrior 2 — in which Chinese forces rescue valiant Africans and Chinese aid workers from villainous Western mercenaries — encouraged the acceleration of this re-purposing process.

The film ends with a picture of the cover of a Chinese passport, and the message: “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China. When you encounter danger in a foreign land, do not give up! Please remember, at your back stands a strong motherland.”

Chinese diplomats now knew their new KPIs. Unsurprisingly soon, a proud battalion of wolf-warrior diplomats began to vent all over the world. The old diplomatic constraints of courtesy and seeking to influence one’s host country and its population through attraction, were discarded like Clark Kent’s shabby reporter’s jacket, as the new “superman cadres” strode the world stage to crescendos of applause back in Beijing, whose approval is what really counts.

Frances Adamson, the secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and a former ambassador to China, told the National Security College at the Australian National University last week that Australia and other countries “have to acknowledge that the United States cannot be expected to lead in the way it once did”, and that “China may have reached a point where it believes that it can largely set the terms of its future engagement with the world”.

China’s top foreign affairs politician, Yang Jiechi, a member of the Politburo, had earlier told ASEAN peers in Hanoi: “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.”

This raises the further question as to whether Australia should concede that the People’s Republic of China is so much more powerful that it should work out an accommodation that is acceptable to Beijing.

Australia is far from the first or only target of Beijing’s commercial coercion or of its wolf-warrior invective, of course. Countries under such attack have ranged from Norway, which awarded the critical philosopher Liu Xiaobo the Nobel Peace Prize, to South Korea, which deployed an anti-missile system to protect itself against the North but which also, Beijing complained, enabled it to see into China’s defences.

And Beijing appears convinced that weaponising its economic heft — its most powerful tool to achieve its international aims — should have forced Australia to start to concede ground well before now.

The Morrison government’s foreign relations bill — which would give Canberra the potential right to cancel Victoria’s Belt and Road deal — compounds China’s overflowing sense of frustration.

Australia is, after Chile, the OECD country that is most exposed to China trade, and each new ban or port holdup or 200 per cent tariff might have been expected to drive exporters to blame Canberra so noisily that it would have had to step down.

But Beijing has misread the Australian economic and political scene. While there is widespread sympathy for the producers, it is some time since the agriculture sector was capable of directing the ship of state. Australia’s economy comprises 70 per cent of services, and as James Laurenceson, director of the Australia China Relations Institute points out, “though the Chinese market for the seven threatened export products is valuable, it’s important to note they represent just 4 per cent of the $150bn in Australia’s exports to China in 2019-20, and less than 2 per cent of the value of all Australian exports”.

And Australia invests directly less in China than in, say, Papua New Guinea — and thus has less on the ground to lose there. In comparison, after South Korea came under attack, a single chaebol conglomerate, Lotte, by last year had lost about $10bn that it had invested there.

Jude Blanchette, the leading China expert at Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in China Leadership Monitor this week: “China’s sui generis Chinese Communist Party Inc system is creating an entirely new political-economic order, one that is already leaving a deep impression on the global order... More than four decades after the death of Mao Zedong, the CCP has proven itself capable of significant – if illiberal – governance innovations, often motivated by fear of losing power. With the increasing geopolitical frictions, this motivation will only intensify.”

Beijing — which has brought Tibet, Xinjiang and now Hong Kong to heel — needs to ensure that Australia defers to it appropriately, primarily for domestic reasons to demonstrate to its own people that it can make its writ run throughout the region, enhancing the Chinese sense of success and stability.

China wants to be surrounded by “tribute states” that defer to it as the paramount power and are in return offered its shield of security and economic opportunity.

If Australia “gets away with it”, others may be tempted to follow.

The prototype wolf-warrior diplomat, foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian, listed on November 17 seven Australian sins. By the following day they had doubled, in a new official list, to 14.

Australians who chiefly blame Canberra for the falling-out have suggested which of the 14 might be conceded to start a process of rehabilitation. Maybe 3, 7, 10 and 12. Others suggest 2, 9 and 14.

In truth, Australia could concede the whole 14 and still find itself facing further lists of wrongdoing. It is in the nature of the kind of relationship that is now being sought by Beijing that trust and respect have to be tested and proven constantly.

China will mount spurts of pressure, and in between play a waiting game, anticipating that cracks will slowly appear in the Australian polity, that the Nationals will need to promote farmers’ fears, that Labor will walk further back from bipartisanship over Beijing, and most importantly that tensions will grow within the US alliance, say over preparedness to defend Taiwan.

Canberra has limited options in response. It can and will encourage continuing diversification of export markets and import sources. It can draw on the experiences of other nations, especially South Korea, that have also for a time borne the brunt of Beijing’s ire. It can work harder to reinforce its partnerships, especially in Asia but also in Europe — which will require investing more in diplomacy and in growing economic relationships.

And as Australian wines are being tariffed out of the Chinese market, they are being rebadged as “Freedom Wine” around Asia, starting in Taiwan. That may be the start of something new.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute and the author of a new paper on China’s Elite Embrace, published by the Centre for Independent Studies.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout