As the Russia-Ukraine war enters its third year, how will this end?

In recent months there have been reports that Vladimir Putin may be interested in a ceasefire and territorial negotiations. But we need to beware such a KGB trap.

As Russia’s war on Ukraine enters its third year, we need to ask: How will this war end? I will examine first how the military fight is changing and what the prospects are for winners and losers. Second, what are the possibilities for a ceasefire and negotiations aimed at an enduring peace? Third, what are the risks of this war extending further into neighbouring NATO countries? Fourth, if the aim of the US and its NATO allies is to defeat Russia, how will this be achieved against a country with 1500 strategic nuclear warheads? And fifth, what would a defeated Russia look like? A Weimar Germany? Or can we conceive of other outcomes under a new Russian leadership?

But before we examine these critically important questions about peace and war, we need to remind ourselves of the reasons Vladimir Putin alleges he went to war. In that context, we need to take notice of the words of CIA director William Burns: “One thing I have learned is that it is always a mistake to underestimate Putin’s fixation on controlling Ukraine and its choices. Without that control he believes it is impossible for Russia to be a great power.”

Here are Putin’s main assertions:

• Putin repeatedly states that there is no such country as Ukraine and that Ukrainians and Russians are one people sharing the same historical and spiritual space, speaking the same language, and believing in the same Orthodox faith. Before he died in 2008, writer and Nobel peace laureate Alexander Solzhenitsyn proclaimed that Russia (Great Russians), Belarus (White Russians) and Ukraine (Little Russians) should be re-created as a unified Slavic country. After two years of vicious war, most Ukrainians, if anything, are even more determined to reject this Great Russian imperial view.

• Putin claims if Ukraine becomes a member of NATO, it will become a direct national security threat to Russia or, as one of his advisers, Sergei Karaganov, puts it, “a spearhead aimed at the heart of Russia”.

American diplomat and historian George Kennan called the expansion of NATO “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era”.

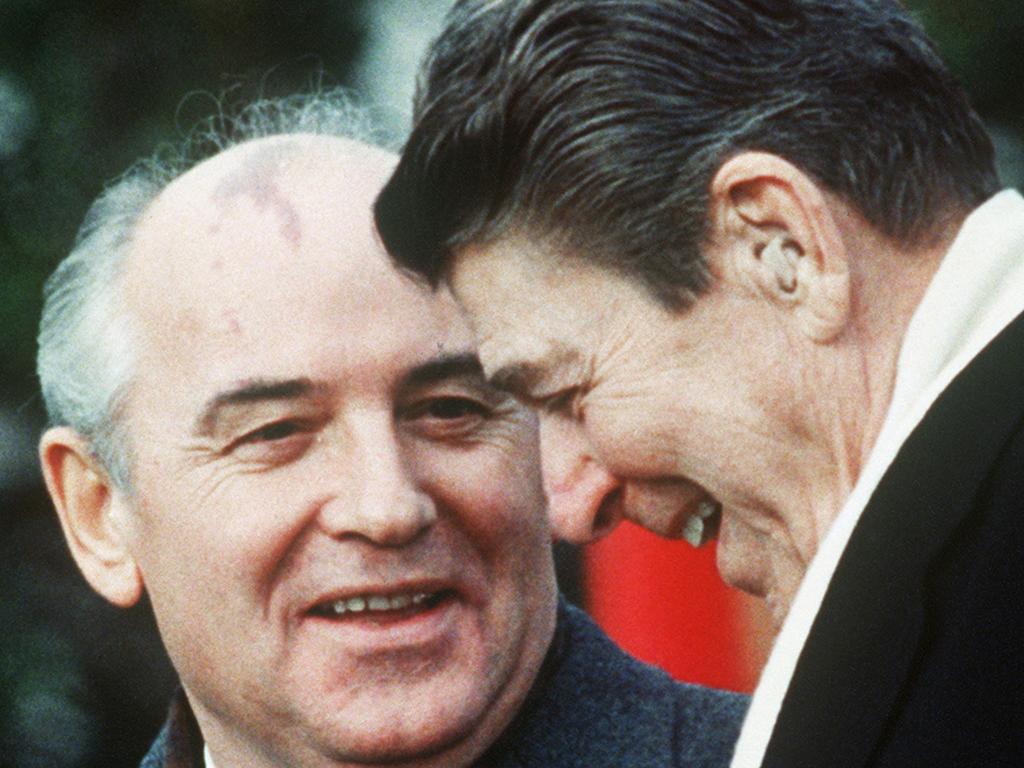

And Rodric Braithwaite, British ambassador to Moscow from 1988 to 1992 and chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee from 1992 to 1993, argues that Western negotiators gave Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev ambiguous assurances that NATO did not intend to expand any further than a unified Germany. However, Braithwaite acknowledges that Gorbachev did not request, nor was he offered, anything in writing.

• Putin tries to argue that it was NATO that cajoled the former members of the Warsaw Pact into becoming members of NATO. That was demonstrably not the case: it was the former members of the Warsaw Pact who were keen to join NATO and be protected from resurgent Russian imperialism. Putin made it clear at the 2007 Munich Security Conference that he viewed NATO expansion as a serious provocation that reduced the level of mutual trust. But, in my view, there were always going to be serious impediments to Russia being invited to join NATO.

Demonstrably, Russia is not a democratic country, and the size of the Russian Federation would have been seen as leading to its natural domination of NATO Europe. The fact is the US can hardly accept the ultimatum Putin has issued regarding Ukraine never becoming a member of NATO.

• From Putin’s perspective there can be little doubt that the way in which Russia has been treated since the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 has been condescending. The Russian national perception of the post-Cold War era continues to be one of humiliation and US hubris that America “won the Cold War”. Putin considers the US took advantage of a gravely weakened Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which allowed the expansion of NATO “to within spitting distance” of Russia’s borders. Gorbachev also accused the US of having a desire “to keep Russia half-strangled for as long as possible”.

• On top of all these obsessive propositions, Putin has introduced a new accusation that the West wants to destroy Russia and Russia “is fighting for its very survival”. According to a recent opinion poll, 64 per cent of Russians believe the war in Ukraine is a “civilisation struggle between Russia and the West”. It is this theme that Putin seems to think has had much more impact among Russians than his previous claim that the so-called nazification of the Ukrainian government was his primary reason for invasion – although he still pursues that naked lie.

• By accusing the West of attempting to destroy Russia’s unique history and culture, Putin is delving back into the disagreements in the 19th century in Russia between those who looked on themselves as Slavophiles and those who were Europeanists. Putin, however, goes much further and encourages Alexander Dugin, the founder of an international Eurasian movement in Russia who borders on megalomania.

The Eurasianists see Russia as the primary geopolitical pole of the land-based civilisations of the world, forever destined to conflict with the sea-based civilisations of the West. Dugin makes the case that it is only by remaining true to the Eurasian path that Russia can survive and flourish in any genuine sense. Otherwise, it will be reduced to a servile and secondary place in the world and the forces of Western liberalism will dominate this world unopposed.

Likely outcomes

So, now let us turn to the likely outcomes of this war and the prospects for some sort of negotiated solution. First, we should examine how the military fight is changing and what its prospects are for winners and losers. This war is now entering its third year and is Europe’s most serious war since the end of World War II in 1945. So far it has experienced essentially two basic phases.

In the initial stages of its invasion, the Russian military performed abysmally poorly – contrary to the prediction of the US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to a closed session of congress, just before the beginning of the war, that it would all be over in 72 hours. This writer admits to being of the same view at that time.

Instead, the Russian Armed Forces encountered fierce opposition – contrary to the advice to Putin of Moscow’s foreign intelligence agency, the SVR – from the beginning of Russia’s attack on Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv.

Rather than the traditional Russian military strategy of accumulating huge, overwhelming conventional forces essentially focused on one target, what we saw was several dispersed attacks by modest-sized battalions across the north of Ukraine. The Ukrainian armed forces proceeded decisively to put Russia’s military on the defensive. This strategy was so successful that mid last year there was much speculation (encouraged by so-called experts in the US) of a victorious Ukrainian summer offensive that would result in Russia’s retreat across the border to its own territory.

The problem with this concept was that the Ukrainians were not thoroughly trained in the American approach to combined arms manoeuvre warfare, and they also lacked America’s air superiority and electronic warfare dominance of the battlefield. Towards the end of last year this resulted in the second phase of this war in Ukraine becoming essentially deadlocked and at a stalemate.

The Russian forces had patiently spent many months creating an impressive defensive array of minefields, tank traps and deeply dug trenches that to many observers is more reminiscent of World War I than to high-speed manoeuvre warfare. The fact is that this modern Western concept is not in the DNA or much of the training of today’s Ukrainian forces, which until the disintegration of the former Soviet Union depended little on unit level initiatives and instead had a deep dependence on centralised military dominance of the battlefield. It remains to be seen if Russia can turn the military tables and now transition to victory over the Ukrainian forces.

At the outset, we need to note that a distinguishing feature of Russian strategy and warfare is a higher acceptance of risk and a lower threshold for the use of force. In his recent article titled “Russia’s Adaptation Advantage” in the journal Foreign Affairs, former Australian Defence Force major-general Mick Ryan argues that if Russia’s strategic adaptation continues to persist without an appropriate Western response, “the worst that can happen in this war is not a stalemate. It is a Ukrainian defeat.”

Ryan is of the view that Russia currently holds the strategic initiative and so, unfortunately for Ukraine, “defeat is still a possible outcome”. But he does not address what the implications of a Russian victory would be for future strategic instability in Europe.

Ceasefire possibilities

We now turn to what are the possibilities for a ceasefire and negotiations aimed at an enduring peace. In recent months there have been reports that Putin may be interested in a ceasefire and territorial negotiations. But we need to beware such a KGB trap.

There has been some speculation in the Financial Times of late that Ukraine might have to bear the bitter price of a permanent peace in which Russia retains part, or all, of its occupied territories in Ukraine. But that would turn Ukraine into a weak, truncated state – nominally independent but at Moscow’s mercy.

On January 22, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said Russia “has always been ready for negotiations”, but he went on to make it perfectly clear that “Russia is only interested in negotiations that result in the removal of the current Ukrainian government from power”. Putin himself consistently refuses to recognise that there is any such separate country as Ukraine and that he would not countenance negotiations with President Volodymyr Zelensky.

And SVR director Sergei Naryshkin said on January 28: “The Kremlin is not interested in any settlement short of the complete destruction and eradication of the Ukrainian state.”

In any case, I do not see Putin under any circumstances handing back Crimea to the Ukrainians. The only way I can see him perhaps conceding to return the 18 per cent of Ukraine’s territory that Russia currently occupies is a decisive Russian defeat on the battlefield. And, even then, my view is that rather than concede victory to Ukraine he is much likelier to perhaps broaden the war to a war in Europe against Russia’s other neighbours such as Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

On February 11, NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg warned that Europe needed to “arm itself for a possibly decades-long confrontation” with Russia. About the same time, Danish Defence Minister Troels Lund Poulsen warned: “It cannot be ruled out that within three to five years, Russia will test the strength of article five of NATO’s solidarity.”

This brings us to the subject of what are the risks of this war extending further into neighbouring NATO countries. I am not arguing here that Putin would casually enter such a high-risk military conflict. But, as I have argued at the beginning of this essay, Putin will simply not accept the existence of a separate nation-state called Ukraine on its borders becoming a full member of the EU and NATO.

One possibility is that he would decide to use tactical nuclear weapons, of which Moscow has more than 2000. Both he and Kremlin leaders such as former prime minister Dmitry Medvedev, as well as international security adviser Karaganov, are being increasingly raucous about the threatened use of nuclear weapons. Even so, I doubt that Putin and his senior military advisers would really relish a full-scale World War III against NATO.

However, the fact is that there have been recent rumblings from the Kremlin about Poland as being historically a traditional enemy of Russia, as well as threats to the Baltic republics about them forcing their Russian populations to undergo a local language test if they are to continue to be citizens.

So far, however, Putin has not attacked NATO countries such as Poland or Germany that continue to facilitate weapons supplies to Ukraine. Nevertheless, my bottom line is that if push ever comes to shove Russia will not accept a battlefield defeat in Ukraine.

And the fact is that if push ever does come to shove, escalation to a full-scale war with Europe cannot be casually dismissed. As CIA director Burns, a former US ambassador to Russia, observes about Putin: “It would be foolish to dismiss escalatory (nuclear) risks entirely.” Describing Putin’s war as a “strategic failure” that “has exposed Russia’s military weaknesses”, Burns, however, does not seem to accept that this may result in Putin escalating to the unthinkable. That brings me to the question: If the aim of the US and its NATO allies is to defeat Russia, how will this be achieved against a country with 1500 strategic nuclear weapons and more than 4000 other strategic nuclear warheads in various states of reserve? And what would a defeated Russia look like? A Weimar Germany angrily looking for revenge?

Such imponderables by themselves should leave us deeply concerned. Or can we conceive of other outcomes under a new Russian leadership if Putin were to be overthrown?

My own view here is that any such new Russian leadership is more likely to be Putin Mark 2 than some form of Western democrat, with all that means for a peaceful outcome.

Impact on China

Finally, we need to address the issue of whether the weaknesses of Russia’s military performance have had an impact on the attitude of China’s President Xi Jinping towards going to war against Taiwan. One would hope Xi would understand what a poor military performance his Russian “friend for life”, Putin, has shown to the world. Xi needs to understand that some of the inherent weaknesses in the Russian military establishment are also deeply reflected in the DNA of China’s People’s Liberation Army.

They include the distrust by authoritarian leaders in both Russia and China of delegating tactical battlefield decisions to non-commissioned officers and the corruption in both countries of their logistics supply and defence industry. Moreover, invading Taiwan across the 200km Taiwan Strait is an infinitely greater military challenge than walking across Ukraine’s border with Russia. Authoritarian leaderships in both China and Russia are typified by deep-seated despotism and pervasive corruption that sap the fighting strength of their armed forces.

Most recently, Xi has sacked several senior generals, including in the strategic nuclear rocket forces, for corruption. Moreover, for more than 44 years now, China has had absolutely no experience of actual military combat. And Xi needs to consider the clear risk in any serious military conflict between the US and China over Taiwan that there is a clear and present danger of devastating escalation to the use of nuclear weapons.

Putin might not have had Alexei Navalny killed if he were sure of victory in his war on Ukraine. As it is, this war is at a stalemate after two years of intensive fighting, which is half the time it took the former Soviet Union in the 1941-45 war against Nazi Germany to destroy what was the finest army in the world.

Today, I see no decisive Russian victories such as Stalingrad or Kursk. This strong sense of comparable Russian history leaves Putin looking very weak.

Paul Dibb is emeritus professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout