‘Anti-Semitism is incurable. We are not ordinary, therefore we have to accept the feelings this invokes in others’

If anti-Semitism is not managed effectively we will find ourselves in a spiral we can no longer exit.

I deliver this oration exactly 18 months from the October 7 attacks. So much needless loss and misery. Israel was dealt a sickening blow on October 7. The pain and shock of those attacks will not remain in that moment. It penetrated the psyche of the people and the nation, and will live with them in the same way that the pogroms of eastern Europe tormented and conditioned the Jews for generations after.

But today, through the sacrifice of the men and women of the Israel Defence Forces, Israel is emerging with the greatest advantage over its enemies it has ever had.

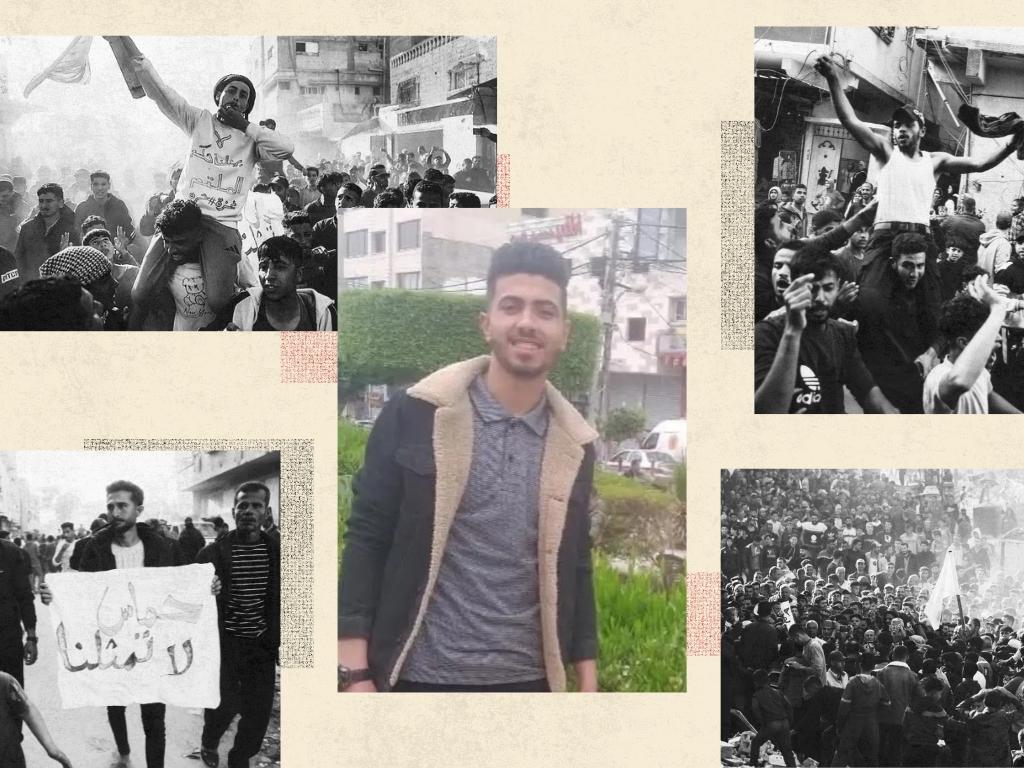

Hamas is decimated. Its ability to wage war is permanently neutralised or at least pushed back by many years. The demonstrations against it in the streets of Gaza, unthinkable for the 19 years of its dictatorial rule, are testament to its severely degraded state and its inability to maintain domestic power, let alone project it outward.

The Iranian regime is at its lowest point, its isolation in the region spectacularly demonstrated by an alliance of the US-Saudi Arabia-Jordan and Israel that together repelled its ballistic missile strikes on Israel.

Hezbollah is battered and humiliated and its figurehead, long believed beyond reach, is dead. The Assad dynasty in Syria is no more and the country is in chaos.

A Trump White House will bring short-term alignment on some matters of policy – opposition to university encampments that have glorified violence and menaced Jewish students, the necessary defunding of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in the Near East, backing Israel at the UN, and a willingness to consider paths to peace beyond tired and disproven paradigms about unilateral recognition of a Palestinian state.

Trump also surely will accelerate the collapse of bipartisan support for Israel, given that anything he closely supports is immediately rendered incapable of being a consensus issue.

At home, we stand on the cusp of a federal election that I believe will be the most fateful our community has ever experienced. It will be the first where large numbers of Australian Jews will vote on the basis of which party can best keep Australian Jews safe and which party will continue to view Israel as an ally.

All of these events and forces, global and domestic, have once again thrust the Jews into the centre of the world’s focus. Here and around the world, the Jewish question is on the agenda once again.

There is a reason the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ignites our streets, cultural institutions, campuses and workplaces like no other issue. And it has nothing to do with loss of life or civilian casualties. The Russia-Ukraine war, wars in Yemen and Syria have been far deadlier.

It has nothing to do with geopolitical importance. The notion that resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is central to achieving regional or even world peace has long been discredited. The rise of Islamic State, the competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the tribal and sectarian rivalries that have ensnared Syria, Iraq and Yemen, have precisely nothing to do with the presence of a tiny Jewish homeland on the edge of the Mediterranean Sea.

As Morocco’s King Hassan II observed, “Rejection of Israel is the Muslim world’s most powerful aphrodisiac.”

It is an article of faith, a rallying cry, but it has no bearing on the chaotic relations, interests and grievances within the Arab world.

The reason the Palestinians matter so much to those with no connection to them and no great understanding of them was best explained by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

“The interest in the Palestinians stems from the interest in the Jewish question. The interest is in the Jews, not in the Palestinians,” he said. “The Palestinians have the good fortune of having Israel as their enemy because the Jews are the centre of attention. And the Jews have brought the Palestinians both defeat and renown.”

It is only when the lives of Palestinians collide with the Jews that there is interest in them because, by observing this interaction, the world is able to draw inferences about the nature of the Jewish enigma and come closer to solving the Jewish question.

Persecution of Palestinians by the Assad regime, their starvation in Yarmouk, their discrimination in Lebanon, has never concerned anyone beyond the victims themselves because there were no Jews in the story.

Those in Gaza who finally march against Hamas, an organisation that has brought them only squalor and ruin, may expect the well-organised and funded campaign that calls itself “pro-Palestinian” to throw its weight and influence behind their brave stand for a better future.

They will get nothing. This is because supporting ordinary Palestinians against Hamas would require those campaigners to admit that Hamas is at least partly responsible for the suffering of Palestinians. And this would unravel pro-Palestinian propaganda, which has strictly contended that Israel and its supporters in the West are the root of all evil.

The other inconvenience arising from the protests in Gaza is that they demonstrate that it took Israeli force to liberate Palestinians and afford them freedoms their own leaders have never entrusted them with.

A further feature of the fixation on the Jewish question is the focus on Zionism, a national movement that achieved its primary goal of an independent Jewish state nearly eight decades ago.

Zionist thinker Leo Pinsker was convinced that Jews were not hated because of their religious beliefs or on any social or racial grounds. Rather, it stemmed from the peculiar position in which the Jews had found themselves.

Their abnormality incited abnormal responses. They had lost their original homeland but continued to exist as a nation in spirit, and did so living everywhere but nowhere in the right place.

This gave rise to what Pinsker called Judeophobia, which he described not as a typical prejudice but as a sort of fear of ghosts.

“The world saw in this people,” Pinsker explained in his 1882 pamphlet Auto-Emancipation, “the sinister figure of a dead person wandering among the living. This ghostlike apparition of a wandering corpse, a people without unity and structure, without land or other ties, who is no longer living yet still walking among the living; this bizarre figure, practically the only one of its kind in history, without a model and without a copy, could not help but generate a peculiar, strange impression in the imaginations of the nations.”

Pinsker realised it didn’t matter how the Jews behaved or contributed. They were feared because they could not be placed. They could not be made sense of.

In Poland, for example, they lived for a thousand years, grew to 10 per cent of the population, yet they were not Poles. They prayed to a different God, observed their own calendar, celebrated their own holidays, pushed away the foods of the host. As Joseph Stalin said of the Jews, “You can’t eat with them and you can’t drink with them.”

What did they want? To whom were they loyal? How did they get here? By what fiendish designs did they survive Egypt, Rome, Greece and Babylon?

Napoleon Bonaparte was so perplexed by this people that he convened a Council of Jewish Notables, made up of 100 Jewish elders, and posed 12 questions to them to figure out just what on earth they were and what they might do with enhanced rights.

Mark Twain, who was fond of the Jews, observed this same quality of immortality. In Harper’s Magazine in March 1898, he wrote: “The Jew has made a marvellous fight in this world, in all the ages; and has done it with his hands tied behind him. The Egyptian, the Babylonian and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendour, then faded to dream-stuff and passed away; the Greek and the Roman followed, and made a vast noise, and they are gone. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains.”

Twain viewed Jews favourably but still as an enigma endowed with supernatural qualities.

The Jews were not hated because of myths about abducting and torturing Christian children or gathering in cemeteries to plot the downfall of humanity. The feelings of hatred came first. The stories were simply manufactured after the fact to rationalise the hatred, justify the abominations of anti-Semitism and recruit others into it.

Consider the stories that accompany the Jews: poisoners of Mohammed; betrayers of Christ; abductors of children; nocturnal schemers. This is no common racism. In time, those who sought to rid society of Jews were able to turn the Jews into precisely that which their myths and spook stories said they were, to prove their point.

Pope Innocent III said the Jews “are consigned to perpetual slavery”. Peter the Venerable said God wished for them “a life worse than death”.

God had not consigned the Jews to perpetual slavery or given them a life worse than death. It was the laws of man that did this. Laws that confined Jews to ghettos, prohibited them from continuing as merchants and craftsmen, banned them from obtaining academic degrees or attending banquets and festivities, as the Council of Basel decreed in 1434.

This impoverished them, degraded them, isolated them, thereby proving the slander about them being a loathsome and degenerate people who had lost the favour of God. This in turn justified ever more measures and indignities against them.

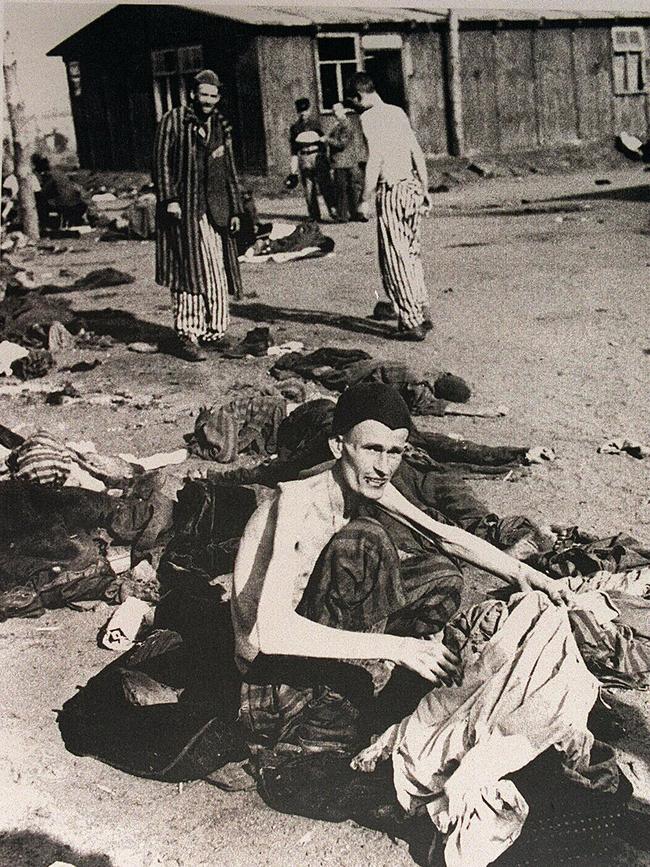

The Nazis, of course, perfected this self-fulfilling perversion. The Nazis characterised ordinary people living ordinary lives in town and cities as vermin and then starved and sickened them to turn them into the wretched, diseased nation the Nazis said they were, justifying their mass destruction appropriately carried out with a common pesticide.

The Zionist leaders logically theorised that if the source of all this hatred was the peculiar Jewish condition of having no centre, no homeland, no living roots, the answer would be to give them that which they lacked, that which made them different, a homeland.

As Thomas Jefferson observed in a letter to fellow US founding father John Adams, “what is most valuable to man (is) his right of self-government”. By attaining this right for the Jews, it followed that they would take on the same value as other nations.

But the Zionist leaders were wrong in one critical respect. They thought that giving the Jews their own state would extinguish this irrational conception of them and endow the Jews with that quality they needed to no longer be feared and hated: ordinariness. But this failed for two reasons. First, the conception of the Jews shaped and reinforced across thousands of years of national traditions, fables, art, liturgy and popular culture could not be undone.

Second, the Holocaust and Israel’s rebirth did not finally show Jews to be ordinary, “fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as” every other nation. It proved the opposite.

Why else would the most elaborate human enterprise ever devised be for the sole purpose of exterminating them?

And how else could they survive this, pick up what was left and proclaim their homeland within 36 months of liberation?

They just proved Twain’s view of their immortality. Or the anti-Semite’s view of their ghostliness.

Once the sympathy for the greatest crime ever committed predictably dissipated, the world would again see the Jews as an irritant, a riddle, a problem to be solved. Why? Because there is nothing normal about us and everyone can see that.

Monotheism was not normal. To believe in a single, all-powerful, ever-present divinity that demands we adhere to a strict moral code and ethical standard of living was not normal. It was a revolution.

To march out of bondage in Egypt as a free people and a distinct nation was not normal. No one else did that.

It is not normal to have your homeland taken from you and renamed to show you it is no longer yours; to be dragged off into every corner of the world and then cling to your culture, traditions and memories under unbearable duress for two millennia and survive as a people.

Not only survive but often outperform despite every disadvantage, making yourself indispensable to kings and sultans, riding the tide of enlightenment, standing at the head of every human achievement from socialism to nuclear fission, from psychoanalysis to motion pictures. There is nothing remotely normal in this.

And there is something uniquely subnormal in being plucked out, marked, plundered, humiliated, herded and murdered in our millions in human abattoirs. And then to ordain a new Jewish state, to fight off the invading armies, not of hordes or militias but the standing armies of seven states, and emerge with the most powerful, innovative and progressive country the Middle East has ever seen.

This all leads me to several conclusions. The first is that anti-Semitism is incurable. After thousands of years, it can no longer be characterised as a defect in reasoning that can be untaught. We are not ordinary. And we therefore have to accept the feelings this invokes in others.

The second is that if one of the stated aims of Zionism was to create, as Pinsker said, a “new consciousness that Jews are a nation like all other nations”, Zionism failed in this respect.

But this failure, the perennial abnormality of the Jews and the incurability of anti-Semitism, means that a sovereign Jewish homeland capable of ingathering and sheltering Jews at any time, capable of safeguarding Jewish scientific and cultural achievements, capable of giving the Jews of Melbourne and Montreal somewhere to gaze out on to when misfortune strikes, is a non-negotiable. It is the only true guarantor of Jewish human rights and of the foremost human right – the right to live.

When someone opposes Zionism they are not opposing the government of the State of Israel, or any of its policies, nor are they expressing solidarity with those they perceive to be harmed by the state or its policies. They are opposing, whether they realise it or not, something essential to being Jewish. The recognition of the Jews as a national group. The right of those people to equality. The right of those people to survive in a world that routinely slanders, dispossesses and destroys them.

This is why generations of Jews have felt a connection to the Zionist project. It has nothing to do with political parties or the politicians of the day. It is immeasurably greater and deeper than that. It is a connection to the Jewish story and to our basic rights. This is why Zionism is the idea that unifies the Jewish people more than any other.

And if someone declares themselves the enemy of what Zionism is and what it means, they’re going to have to come and take those rights because we will never surrender them.

This is why, when we hear chants in the streets of this city (Melbourne) that “all Zionists are terrorists”, we know it is the defamation of our people and the desire to strip us of our rights.

We see the same thing when Randa Abdel-Fattah, the Macquarie University academic, uses her publicly funded platform to declare: “If you are a Zionist, you have no right or claim to cultural safety.” In other words, we should expect to be endangered.

And we see this when David Miller, who taught at Bristol University, takes the next logical step and proclaims: “There are Zionists everywhere. In every town and city. Find out where they are.”

What, then, does all this mean for the fight against anti-Semitism? If anti-Semitism is a disease with no cure, why fight it at all? If it has been embedded in the human consciousness across thousands of years, why would a little education dislodge it?

We may not be able to eradicate anti-Semitism fully but if we do not effectively manage it through advocacy and education, it will pose a constant threat to our lives and to our way of life.

As we have seen, when anti-Semitism is left uncontrolled, Jewish artists, writers and musicians are deprived of the ability to create and do what they must do, which is to share their work and their talent.

It means that Jewish high school students will feel they have no place outside the Jewish school system, which in turn diminishes contact between Jews and non-Jews, leading to even greater animosity and distrust.

It means that Jewish university students will again be urged to remain off their campuses or retreat into safe rooms.

It means that each time a Jew steps out on to the city streets in a kippa or with a Star of David, it will be an act of defiance rather than a humble show of faith.

If this becomes the norm, and it has already been the norm for 18 months, it will mean that Jews alter their behaviours, their professional decisions, their social interactions in a way that may be imperceptible at first but eventually will lead to a radical shift in Jewish-non-Jewish relations in this country.

We will backslide into a time when Jews were sequestered in Jewish law firms, Jewish social clubs and Jewish galleries and publishers, not as a choice to enhance continuity and preserve identity but from fear and exclusion.

The Jewish contribution to wider society, which has enhanced enormously the culture, science and wealth of the nations, will be severely reduced. As will our opportunity to be defined and understood for who we really are, and not by folktales and disinformation of mendacious online influencers. Then we will find ourselves in a spiral that we can no longer exit.

There is, of course, a positive dividend to everything we have been living through – the renewal of Jewish pride and association, which bodes well for continuity. But we need to find a way to manage anti-Semitism so Jews can feel proud without feeling imperilled.

If we fail in this, Jews will be forced to choose between their Jewishness and other parts of their identity, as progressives or artists, for example, and the result will be discontinuity and loss.

This is why education on the nature of anti-Semitism, specifically confronting the mythology and conspiracy theories through which it is all transmitted, is so vital.

Equally, we must deepen the engagement with the non-Jewish world. The mythological Jew and the real Jew cannot coexist in the same space. Wherever the real Jew is absent, the myth will be presented in all its scheming, bloodthirstiness and arrogance. But where real Jews enter, you and me, the myth falls away.

The past 18 months have shown me something else. When we experienced October 7, we felt the panic of our vulnerability, anger at our loneliness. We felt what it meant to have a cosmic injustice delivered against us and then have that compounded through celebrations and denials, as it has always been. But we also witnessed why it is that we survive. Through kindness. Through strength. Through personal responsibility.

In these 18 months, I have spoken to and listened to more members of our community than perhaps in the entire 40 years that preceded it. And through the endless days and nights of work, this community, this family of families, has replenished my soul, and filled my heart with love and admiration.

Most of all, it has brought me pride at belonging to something eternal and, yes, something utterly abnormal.

We are a statistical anomaly. Our being here today as Jews, as the legacy of thousands of years of adventure and turmoil, upholding the same truths, the same faith, the same tradition despite so many attempts to change or erase us, is so unlikely that it must make us marvel at the workings of the universe and of the Almighty.

And this surely is the secret to our survival. We know we have been given a rare gift. Something so uncommon, so meaningful, that it is worth all the struggle, the attention, the burden. Because to hold on to what we are and teach it to our children is the highest form of resistance and the greatest victory.

This is an edited extract of the B’nai B’rith annual human rights oration to be delivered in Melbourne on Sunday by Alex Ryvchin, co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, who will be receiving 2025 B’nai B’rith Human Rights Award. Ryvchin is the author of the critically acclaimed works The Anti-Israel Agenda: Inside the Political War on the Jewish State (2017), Zionism: The Concise History (2019) and The Seven Deadly Myths: Antisemitism from the Time of Christ to Kanye West (2023), which investigates the extraordinary conspiracy theories behind anti-Semitism.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout