Where would I go if I wasn't here? Aged-care costs hit home as providers at bankruptcy risk

The things that make 82-year-old Elsie’s nursing home life idyllic are sending it broke. Is another $18 a day too much to ask?

Elsie Vicary is part of the garden committee at Gunther Village, her nursing home in Gayndah, a couple of hours west of Bundaberg. The 82-year-old loves it when the preschoolers come to visit, and she sees a physio every morning to help her along after a stroke. Vicary’s daughter, one of her four children, lives in the small Queensland town and visits her every day. They walk and talk about her 14 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

“I like the outings we have, and the ladies who come in and play us music,” Vicary says. “I love the pots outside my window that I water. They’re pretty and they make the view wonderful.”

An idyllic story of aged care — except that Gunther Village has lost $345,000 a year for each of the past two years, its facilities manager, Vicki Boyd, tells Inquirer, and unless management can turn the finances around by April, they will be forced to “explore their options”. Of which there are effectively two: sell to a bigger provider if one is prepared to take on a loss-making enterprise, or shut down altogether.

READ MORE: Family aged care ‘workers’ need help | Elderly deserve safe care in homes | Bupa cost-save plan ‘too risky’ |

“I would hope that if we looked at another group that they won’t close the home down, but the residents are concerned that the people that will be looking after them won’t be the same people here now,” Boyd says.

“I had a special meeting with residents about us being in financial trouble, so you know what they did? They asked how they could help out. So now they do things like fold the linen. They feel useful, and it shows just how much they want to stay.”

Gunther Villages, a not-for-profit residence for 52 older Australians, employs about 82 people, most part time. Outside the public service, it is the biggest employer in Gayndah, Boyd says.

Other local businesses rely on it as a significant client. It is a stand-alone operation and has been since the mid-1980s.

“If we aren’t here, our residents will have to go to Bundaberg or Maryborough or Hervey Bay. What does that mean for their families?” Boyd says.

Vicary can’t hide her concern. “It does worry me. Where would I go if I wasn’t here? I hope it works out in the long run. It’s a good place. I enjoy being here. I honestly don’t know what I’d do. I just hope it doesn’t happen.”

Frail aged-care homes

This is far from an isolated story. It is being replicated in country towns and capital city suburbs across the country.

An analysis of residential aged-care finances by Leading Age Services Australia last week puts the number of aged-care providers at risk of insolvency at just shy of 200.

LAST estimates that these providers look after about 50,000 residents, nearly a quarter of the nation’s nursing home population.

Another recent financial analyses of the residential aged-care sector by chartered accountants StewartBrown found that, excluding the impact of a one-off government grant, more than 50 per cent of residential aged-care providers ran at a loss last financial year, a proportion that pushes up to more than 66 per cent in the regions.

It is no secret why.

The aged-care sector doesn’t like using the term nursing homes, preferring the less politically loaded term residential aged-care homes. But there is more and more nursing to be done in these facilities.

Older Australians are waiting longer to enter residential care, preferring to stay at home for as long as possible with their own funding or with the support of government-funded in-home care packages, or both.

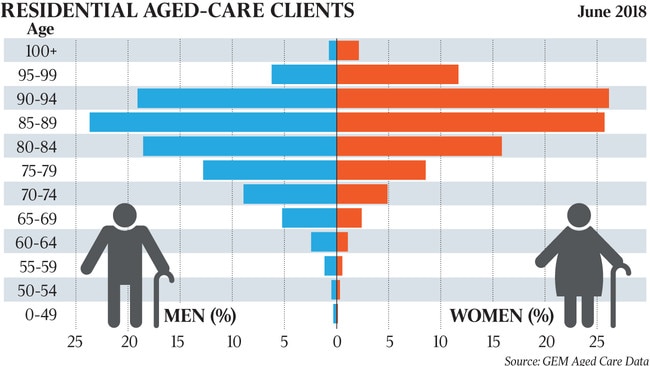

The average age of entry into formal residential care is 82 for men and 85 for women.

They are entering more frail and with higher needs. A greater proportion have dementia. The care needed is more intense, more medicalised, more specialist, more expensive.

“When I started in this business in the 90s, people would still be driving their cars into places like this,” Boyd says.

“Now our average length of stay for a resident would be less than two years.”

Funding not keeping up

For each permanent resident in aged care in 2017-18, the average government contribution to the provider was $65,600. Much of this is for basic care needs, but costs are continuing to increase with the rising acuity of residents and, according to providers, government funding is not keeping pace with burgeoning costs and matters are becoming urgent.

The LASA analysis has prompted its chief executive, Sean Rooney, to call on the federal government to inject $1.3bn into the residential aged-care sector before Christmas as an emergency measure. It is a significant ask.

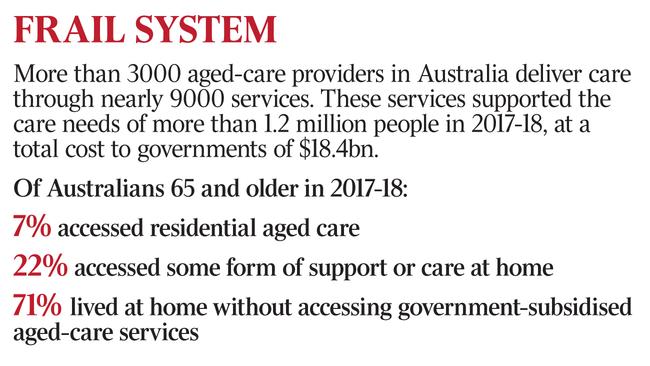

On the most recent government figures, for 2017-18, government recurrent spending on aged care was $18.4bn, of which 12.4bn was for people in residential aged care. In-home care made up most of the rest, at about $5.1bn.

The Morrison government has already committed to a yet to be announced funding boost in aged care in the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook response, on the back of recommendations contained in the aged-care royal commission’s interim report.

But this funding is likely to be directed to the funding shortfall in-home care. Those remaining in their homes also are becoming more frail and need higher levels of personal care, but there are too few available funded home-care packages at this higher intensity to meet demand, and thousands of older Australians are dying on the waiting list before they receive appropriately funded support.

Demographic march

Rooney wonders how aged care in general, and residential aged care in particular, is so underfunded, noting that while the OECD average for government spending on aged care is 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product, for Australia it is 1 per cent.

“If you take a step back, you have to wonder what the hell is going on. How could this be happening in 21st-century Australia — that such an essential service is being so under-supported?” Rooney asks.

The problem is not going away. The demographic march, the ageing of the nation’s population, is only adding to the pressures on the sector. More than 420 people are already turning 75 every day in Australia, a figure expected to rise as the baby boomers hit this age bracket. They have higher expectations than their own parents about their aged care.

“There is a new normal with regard to older people in our communities. We have to work out the best way to support them to age well. At present we’re a long way from being able to respond adequately,” Rooney says.

One of the biggest pressures is wages. Last week the aged-care royal commission used a study of Bupa South Hobart to highlight the tension between costs and quality of care in this “new normal”.

The commission heard evidence of a (now abandoned) formal policy across Bupa Aged Care homes to cut wage costs through a “save a shift” edict, where carers who called in sick weren’t replaced. It heard that even this wasn’t enough to create a break-even point for some facilities.

Walks, gardening, fishing face cuts

In the meantime, the commission heard distressing evidence from family members of inadequate care of their loved ones at Bupa South Hobart, a situation created by a lack of resources.

Boyd has a different philosophy for Gunther Villages.

“One thing I implemented here is a team of lifestyle workers. Most days I have three people on during the day who do none of the clinical care like wound dressing or showering. They run the wellbeing activities and do one-on-one time for those who are bedridden or palliative,” Boyd says.

“The residents love it, it makes a huge difference. Our residents are happy, it’s good for both their mental and physical health.

“We do walks, gardening, fishing, trips to the coffee shop, trips away.”

Financial dilemma

The tension becomes obvious. These services, which residents crave, because a nursing home is a home and not a hospital, are provided in a facility losing $345,000 a year and facing closure or consolidation within months.

Boyd says she already has cut them back a little, but to strip any more away would take away the essence of what her residents want.

That is the financial dilemma facing the industry, in part because government funding hasn’t kept up with the costs of providing quality care, in particular the labour costs, which make up 70 per cent of the total.

“There’s not an aged-care provider that doesn’t want more staff, higher skilled, better-quality staff that are better paid,” Rooney says. “Because that’s what their clients want and need. But while costs have increased, the funding from the government has simply not kept pace.

“Salaries have gone up, with minimum wage increases of between 3 and 3.5 per cent for a number of years, but the government subsidy increase for the last three years has either been zero or less than 2 per cent.”

‘Another $18 a day isn’t a lot to ask’

Kerri Rivett, chief executive of Shepparton Retirement Villages, explains the numbers. Her financial situation is slightly different to that of Gunther Villages, in that she runs not only 300 residential aged-care beds but also 300 people in retirement living, and several in-home care packages.

Rivett is blunt in her assessment of the financial sustainability of residential aged care. “Basically we don’t get enough money to take appropriate care of the clients in our care,” she says.

“We get around $170 a day on average from the government under the aged-care funding agreement. We also receive 85 per cent of a resident’s pension, which works out to about $51 a day. Combined we have about $230 a day to deliver 24-hour care and services, six meals a day, showering, nursing, physio, occupational therapy, dietitians, laundry, electricity, gas, water, rates, gardening, maintenance,” Rivett says.

“Complex care needs are increasingly common as people wait longer to come into residential care and come in more frail. Most residents now have high needs. It is complex to manage, both from a staffing and equipment point of view.”

Rivett says the Shepparton facility is spending more on care than the income coming in, and it is able to continue to deliver care for its 300 aged-care residents only by subsidising the costs from other parts of the business.

“Even so, if we don’t rectify this within a couple of years, we will be in the trouble that some other organisations are in now,” Rivett says.

“To make numbers balance for us, and to give our residents the care they should have, we reckon we need another $18 per resident per day from the government. I don’t think that’s a lot.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout