Prelude to a legend

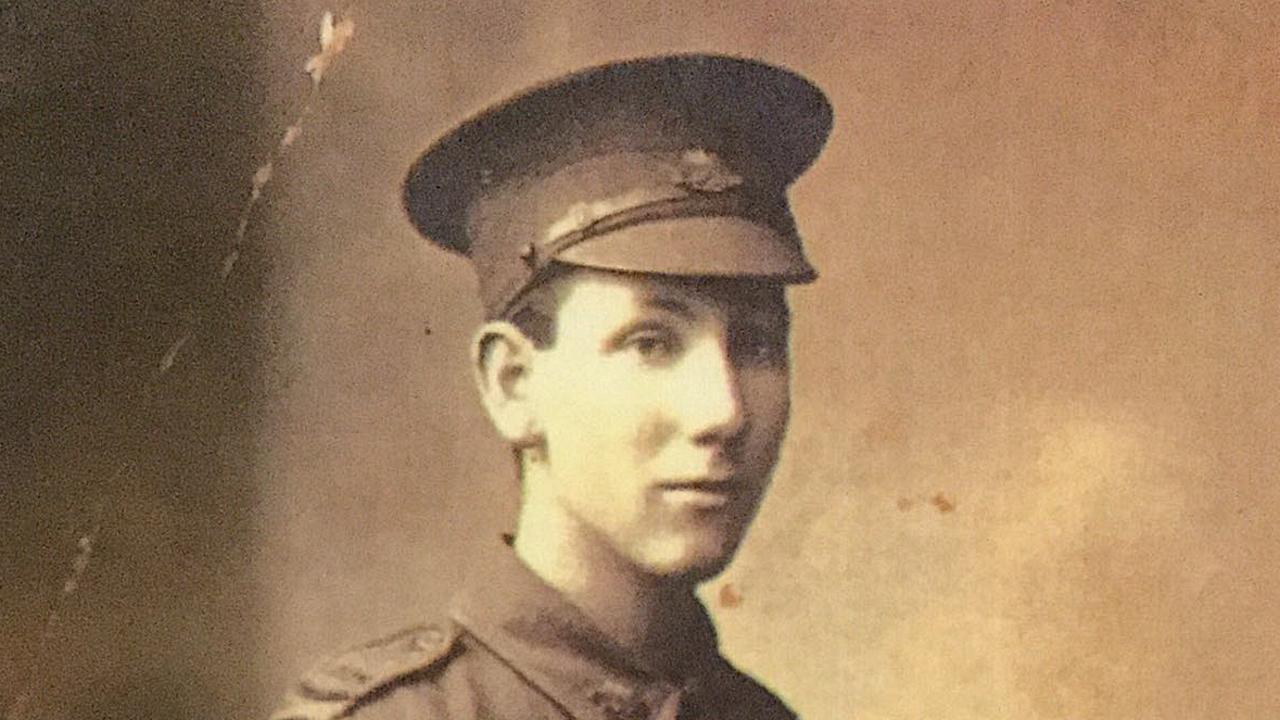

THERE is something compelling about the young man who looks shyly out at us from the Portrait of Spicer Cookworthy, which hangs in the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

THERE is something compelling about the young man who looks shyly out at us from the Portrait of Spicer Cookworthy, which hangs in the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

It isn't his face, since the unknown artist's talent was too limited to capture much of a likeness. No, it's the red coat he's wearing, the signature piece of uniform worn by the British army before the machine gun and aeroplane.

The colour is eye-catching enough, but amid the brown, open landscapes of the early colonial art surrounding it on the wall, it stands out as heraldic, antique -- foreign, perhaps.

But there was nothing foreign about Cookworthy or his red coat. Raised in WA, the young man decided to become a professional soldier. In the middle of the 19th century, that meant joining the British army.

He wore the uniform for a dozen years on three continents before coming home, but his connection with Australia was always there. The British army was then Australia's army, too. And in a forgotten rehearsal for what 50,000 Australians would undergo a couple of generations later, Cookworthy's first experience of war was at Gallipoli.

It was a very different, almost idyllic experience compared with the fighting and disease the Anzacs would come to know in 1915. Still, to remember the first Australian soldier's encounter with that Turkish peninsula is to be reminded that the Australian military story stretches back long before 1915, and notonly to frontier fighting between colonists and Aborigines. Those colonists were always interested spectators in the wars the British army was then fighting, however far from their new home, and a few of them became participants.

One in five Anzacs who fought at Gallipoli was born in Britain. So too was Cookworthy.

His name invoked the modest fame his family had won. There was William Cookworthy, who had made the first fine china in England and and who dined with James Cook and Joseph Banks as they prepared for the voyage that charted eastern Australia in 1770 and prompted British annexation. There were also the soldiers and sailors among his Spicer relatives who had fought in the wars against Napoleon Bonaparte.

Cookworthy might have lived his life in England, and as a pacifist, too, after his parents joined the Plymouth Brethren. But when his father died, his mother remarried, and her new husband was a conventional Anglican. He was also head of a clan that was pioneering British settlement around what is now the town of Busselton, north of WA's Margaret River. So in 1839, as Cookworthy approached his teenage years, he and his family sailed across the world to join a small, remote community of farmers, servants and soldiers.

Those soldiers belonged to the British army. Their presence was so common in colonial Australia it probably doesn't explain why Cookworthy decided on a military career. Likelier reasons are the example set by his martial relatives, along with the encouragement of another veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, a local official named John Molloy.

When Cookworthy turned 18 his parents sent him to England to further his education and begin a career in the law or the church, but these professions were the last thing on his mind. In his pocket was a letter of introduction from Molloy to a senior army general. Despite democratic legend, the army that Australia sent to Gallipoli in 1915 was officered largely by men from the middle class who had spent some time in uniform but had never been to war.

Cookworthy fitted that profile when he joined the British army in 1851 as a junior lieutenant and, after three easy, peaceful years with an infantry regiment stationed in Ireland, went to war, responsible for the lives of dozens of soldiers. He had gained his rank simply by paying for it. He paid an even larger sum for his uniform, including the beautiful full dress worn in his portrait.

Choosing junior officers for their money more than their merit was much criticised at the time, and it stopped talented lower-rank soldiers from becoming officers. At least it prevented the aristocracy from turning the officer corps into a hereditary club. And if Cookworthy had stayed in Australia and taken the more common military path of joining the part-time, community-based Volunteer Corps that was formed across the land in the 1860s, he would still have become an officer overnight by virtue of his literacy, his class and his connections.

The war to which Cookworthy and his regiment headed in March 1854 is known to history as the Crimean War. That name is misleading, since there was fighting in eastern Europe, central Asia, the Baltic and the Pacific as well.

The aim of the war, from Britain's point of view, was to prevent a large part of the Ottoman Empire, which then included the Balkans, from being swallowed up by Russia. The war was being fought to prop Turkey up; 60 years later the Gallipoli campaign would be fought to knock it down. Such are the well-known if frequently lamented realities of power politics.

In March 1854 the front line was where the Danube River joined the Black Sea, but Cookworthy and the rest of the British army were not landed there to support the struggling Turks. London wanted to make a show of force, perhaps prevent a Russian attack on the Turkish capital, Constantinople (Istanbul), and certainly keep the Russians out of the Mediterranean Sea.

Some British troops landed at Scutari, now one of Istanbul's suburbs and where Florence Nightingale would soon make her reputation saving the lives of sick soldiers.

But most of the army headed for the flat, fertile north of a peninsula that dominated the narrow Dardanelles through which any Russian ships heading for the Mediterranean would have to pass. Thus it was that in late April or early May, 1854, 61 years before any other Australian soldier, lieutenant Cookworthy of the 1st Battalion of the 1st Regiment of Foot, better known as the Royals, splashed ashore atGallipoli.

The Gallipoli landing by the Anzacs on April 25, 1915, was a shambles but inspiring nonetheless, literally the stuff of legend. Cookworthy's was anything but. Having come to invade Turkish territory, the Anzacs were welcomed by bullets. Having come to defend it, the Royals were welcomed by peddlers.

The Anzacs hunkered down in a cramped cove on the western side of the peninsula; the Royals spread themselves across broad, flat ground in the north near the run-down little town that gave the peninsula its name and which the troops would soon dub Gallip. ``Of all the bastards of places,'' one Anzac wrote in September 1915, ``this is the greatest bastard in the world.''

But in 1854 the peninsula was a haven of sorts for Cookworthy and the rest of the redcoats. ``We landed at Gallipoli on the 11th (of April),'' one English corporal wrote to his father, ``and I have to inform you that it is as fine a country as ever my eyes did see.''

It was a hot, treeless land but rich in crops and game, wine and olives, coffee, mutton and bread. The troops set up camp, though lacking tents at first, while their officers began the frequent sports and race meetings they amused themselves with for the seven weeks the army would spend on the peninsula.

The idyll could not last. Whenever the army moved about it was punished by a burning sun made worse by poor choice of clothing. Cookworthy arrived in that beautiful full dress, the rest of the troops likewise. They had worn comfortable smocks while at sea but left them on the ships. They had worn light jackets in barracks back in Britain but had to leave them there. Cookworthy and other officers had comfortable semi-civilian clothes to change into whenever the generals' eyes were turned, but their men had nothing but full dress.

The worst parts of that dress were the cylindrical leather hats called shakos, intended to make men look taller in battle, and the tight leather stocks worn around everyone's neck, devised to prevent the instinctive ducking of heads when the bullets started flying.

Contrary to publicity at the time and legend since, these were tactically useful items of clothing in an age when battles were fought close-up; but they were torture to wear on peaceful Gallipoli.

Together with heavy packs, neck stocks made marching soldiers turn ``red in the face as turkeycocks'', Irish war correspondent William Howard Russell reported.

Shakos grew so hot in the sun that Cookworthy's colonel could fry a slice of bacon on his, and make the regimental doctor eat the result. Relief of sorts soon came. The troops were ordered to throw their stocks away and to turn their collars down, and white linen shako covers were issued.

Yet these measures did not really ease the discomfort the army felt as it got down to work. It had three tasks, the first being the massive and ultimately futile one of digging a line of trenches and forts across the narrowest part of the peninsula past the village of Bulair in case Russian troops attacked.

Had the Russians done so, Cookworthy would have found himself defending Gallipoli rather than attacking it, as the Anzacs were to do. But the Russians stayed on the Danube and the vast earthworks were never tested. The ``famous system of fortifications known as the Bulair Lines'' were seen by Russell's Australian counterpart of 1915, Charles Bean, when he visited the peninsula after World WarI to walk the battlefields he would describe in his monumental official history of the Anzacs at Gallipoli.

With the enemy so far away the army could busy itself with its second task, training for war. And as it marched along sandy roads and manoeuvred in cornfields, it also engaged in its third task, learning to get along with its ally. As with the Anzacs, or rather the British army they were a part of in 1915, that ally was France. But in 1854 the French alliance seemed uncomfortable and fascinating.

Britain and France had been enemies for the past 150 years, and as France was ruled by a nephew of Napoleon, it still wasn't quite trusted. Yet the French army was vastly admired, indeed, envied. The astonishing victories it won during the Napoleonic Wars had somehow outlived its eventual crushing defeat, and now, on Gallipoli in 1854, it was showing a confidence and a professionalism that made the British army look amateurish.

And if most Britons had been raised on the notion that France was their greatest enemy, a notion just as strong among colonists in Australia as their cousins back home, they were ecstatic at being able to join French troops in their traditional show of support for a Napoleon, even a third-rate nephew of the great man.

When the Royals marched into Gallip to exchange their muskets for new, more accurate rifles, and French troops played God Save the Queen in their honour, Cookworthy and his men replied with wild cheers of ``Vive l'empereur!'' The two armies soon got along, especially when drinking together.

Then again, the British army in those days would have found any reason to drink to excess. It was inclined to recruit drunk, waste time drunk, parade drunk, even fight drunk.

It was the army's drinking with the French that helped Karl Marx, who at the time was earning a meagre living as a foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune, to write off the army's presence on Gallipoli as a waste of time and money. ``The Allied land forces,'' he reported, ``fraternise at Gallipoli and Scutari in their own way, annihilating enormous quantities of the strong and sweet wine of the country. Those who happen to be sober are employed upon the construction of field works, so situated and so constructed that they will either never be attacked or never defended.''

If any proof was wanted that Britain and France had no intention of doing Russia any harm, Marx predicted, this was it. Like most of Marx's predictions, this one proved wrong. Early in June 1854 the Royals shifted camp to a fine position by the sea where they watched an endless procession of ships carrying supplies, munitions and more troops into the Black Sea and towards the front line. It promised real war at last. ``Gentlemen,'' the regiment's colonel suddenly announced one morning, ``we embark at four o'clock this day.'' Gallipoli had been almost enjoyable for young Cookworthy and the rest of the officers, sometimes for men in the ranks too; but no one was sorry to go. Soldiers hadn't yet learned to dread going into battle.

Eight months on Gallipoli in 1915 cost the Anzacs 8000 dead. The British troops who camped on Gallipoli for seven weeks in 1854 did not even lose a noticeable number of men to the diseases that in those days plagued armies.

``We stayed successively at Gallipoli and Varna (by the Black Sea) for some time,'' Cookworthy wrote to his parents in WA after leaving the peninsula and he was at last experiencing real war, ``and suffered what we called hardships and privations then, but what we should think ease and luxury now.''

Still, the army felt it had achieved something, if only by deterring a Russian attack. When Cookworthy eventually left the army and was looking for a civilian job or a staff post with the Volunteer Corps he included ``landing at Gallipoli'' on his CV. He was the first of many Australians who would later do so.

He resembled later Gallipoli veterans in another way, too. They left the peninsula for the trenches of France and Belgium; he left it for the trenches of the Crimea. The Royals sailed past Istanbul, the goal of the 1915 campaign, and after camping at cholera-ridden Varna joined in the siege of the Russian naval base at Sevastopol on the Crimean peninsula.

After 11 months the British and French eventually stormed the base, but along the way lost thousands of dead, mostly during a winter when clothing once again proved inadequate and supplies broke down.

Young and healthy, Cookworthy survived the conditions that killed dozens of men around him each week. But he lost his enthusiasm for war. In words that many a later Gallipoli veteran would have understood, he wrote home from the trenches that peace was something ``I pray most earnestly for, having had quite enough of fighting''.

Cookworthy's Gallipoli landing reminds us there was a trickle of young Australians who sailed to Britain during the 19th century to serve in the British army. Apparently it's something we need reminding of. The AGWA has expertly restored and proudly displayed the Portrait of Spicer Cookworthy, but believes the painting was done in the colony despite proof to the contrary in family letters held by the State Library of WA just 100m away.

That a young Australian would have sailed for England, joined the British army and served in an earlier and very different Gallipoli campaign is just too strange a thought to those of us who were raised on the notion that the Australian military story started on April 25,1915.