Words of war: Private tales from the Western Front revealed 100 years on

Reading his father’s war diary all these years later, Noel Casey is humbled by what brave Australians did at Villers-Bretonneux.

Reading his father’s war diary all these years later, Noel Casey is humbled by what those brave, obstinate and reassuringly laconic Australians did at Villers-Bretonneux while the whole world held its breath.

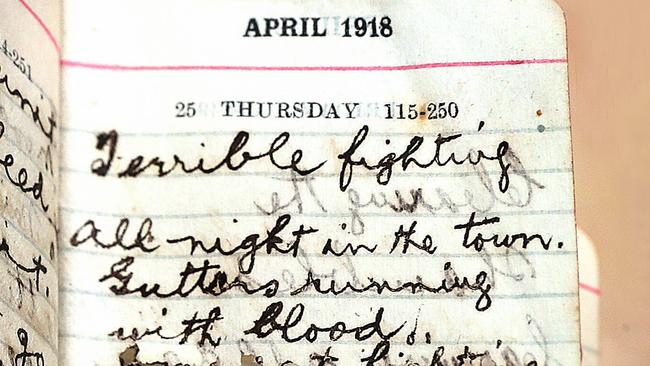

“Terrible fighting … Gutters running with blood. Bayonet fighting in the houses and rooms,” Private John Casey wrote on Anzac Day, 1918, after the Diggers clawed their way into the shattered French town.

“Snipers everywhere. Plenty of dead and wounded. A night not easily forgotten.”

The climactic battles in and around Villers-Bretonneux not only sealed the fate of the Kaiser’s army, but marked the coming of age of a young and uncertain nation that would take solemn pride in its role in turning the tide of World War I.

This was a very different Anzac legend from the one forged in the futility of Gallipoli or the mud and blood of the trenches on a stalemated Western Front. Villers-Bretonneux was the great denouement of the Great War, fought after the Germans risked it all on one mighty push to deliver the knockout blow that had eluded them since 1914.

The offensive was halted at Villers-Bretonneux, on the downlands of northern France, mainly by Australians who refused to yield. In a month of bitter fighting, the linchpin town would be saved by the Diggers, lost by British troops and then recaptured in an all-or-nothing Australian bayonet attack on April 24-25, 1918, that ripped into the stunned Germans. Never again would they hold the initiative.

A century on, Anzac Day next Wednesday will be marked by the unveiling of the $99 million Sir John Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux, a museum honouring the feats and sacrifice of Australians on the Western Front. Malcolm Turnbull will be there, along with Mr Casey, 81, and other proud descendants of the men and women who served selflessly, far from home in WWI’s defining theatre.

GRAPHIC: Digger's World War I journey

While his father was happy enough to talk about the war, Mr Casey had a nagging suspicion there was more to the story. And so there was, spelled out in the spidery handwriting of an ordinary young man from Brisbane who found himself doing extraordinary things after he threw in his job as a railway clerk and joined up in January 1916, aged 19. A big, strapping fellow, Private Casey was made a stretcher-bearer and assigned to the 7th Field Ambulance, which had been blooded in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. He went into battle unarmed, part of a four-man team whose job, to retrieve the wounded and dead, was every bit as dangerous as that of the frontline soldier.

At Passchendaele, he was hit by shrapnel the day before his 21st birthday. The shoulder wound was serious enough to send him to England for treatment.

Back for the last gasp of the battle in November 1917 — Passchendaele was an unremitting horror for the Australians, fought in oozing mud that could drown a man — Private Casey contracted “trench fever” and was pulled out of the line. This arguably saved his life: more than 38,000 Australians were killed or wounded there, capping a brutal year in which the AIF was bled white by nearly 77,000 casualties. Somehow, Private Casey found the time and energy to keep up his journal. He carried the small, red leather-bound diary in his tunic pocket through thick and thin.

“Big guns usher in New Year,” he wrote on January 1, 1918, from his billet in Pont d’Aschelles, near Nieppe in northern France. It was snowing and bitterly cold. He marched miles for a bath.

His unit was sent to Westhof Farm, near Ypres, a staging point the troops knew all too well after Passchendaele. A lull in the fighting had raised their spirits.

“Think the war has finished,” he wrote on March 27 — not realising that the Germans had rolled the dice with Operation Michael, their great spring offensive.

The attack took place on the old Somme battlefield, south of where the bulk of the Australian forces were stationed in Flanders and northern France. Deploying a vast reserve freed up by the withdrawal of Russia from the war in the east, the Germans smashed through the British front, sowing confusion and chaos.

The German generals had gambled they could split the British and French armies and drive to the channel ports, ending the war before the newly arrived Americans could tip the balance against them on the battlefield, or before the home front crumbled under the British naval blockade that would cause starvation and civil unrest in Germany.

And, as the storm troopers advanced on Villers-Bretonneux, spectres in field grey, the plan looked very much like succeeding.

If the town fell, the Germans would seize the city of Amiens, a crucial road and rail hub, and Paris could be next. Who knew what would happen then?

Four Anzac divisions went in, Private Casey’s unit among them. On April 4, he marched through Amiens with the men of the 7th Infantry Brigade, who were cheekily whistling La Marseillaise, the French anthem.

“People overjoyed. Showering kisses and sweets,” he wrote.

This is a soldier’s diary, brisk and sparsely worded. But Private Casey was fully aware of what was at stake. Australian posts were becoming the new frontline as the Brits fell back, often in disarray. The French army was spent. The Germans came within 400m of the town that day, but a fierce assault by the outnumbered Australians, supported by Tommies from the London Regiment, drove back two divisions of attacking troops.

On April 11, as desperate fighting continued, Private Casey moved up to a forward position opposite the village of Cachy and Gentelles Wood. “Pretty hot spot here,” he noted.

The German snipers were busy, compounding the danger.

“Carrying the safest,” he wrote, with a nod to the haphazardly observed convention that stretcher-bearers were to be left alone. Next day, a “fierce and sudden” German assault ejected the 18th Battalion from their trenches, leaving “Fritzes everywhere”.

The Australians regrouped. “Splendid bayonet attack by the 17th and 18th Battalions took the positions again,” the diary reads.

The Germans responded with furious artillery fire, a drumbeat of explosive and shrapnel shells.

“Fritz venting his rage in ironmongery”, Private Casey wrote.

“In a tight corner” on April 15, Private Casey had entered a draw with his mates to decide who would run for rations and the mail, always a prime concern for troops at the front. “Sniping all day makes the place no good. Decide to go to another ‘pub’,” he joked.

Poisonous gas billowed into the Australian lines, causing more than 1000 casualties, before a short ceasefire was agreed with the Germans for both sides to bury their dead. By April 23, he was on the move to Millencourt, not far from Villers-Bretonneux, for a “good feed and a clean shirt”. The unthinkable was about to happen.

After all the Australians had done, all the good men they had lost, the British troops who had taken over the defence of the town panicked when giant German A7V tanks lumbered out of the mist and broke their line. The German infantry poured through.

“Tommies lost the town last night,” he wrote bleakly.

The British counterattacked, but were repulsed. The allied generalissimo, Frenchman Ferdinand Foch, was adamant that Villers-Bretonneux had to be retaken, immediatement. The job, once again, went to the Australians. Two brigades totalling about 4000 men — the 13th under Thomas Glasgow, the 15th commanded by Harold “Pompey” Elliott, both legends of the AIF — went in at 10pm on the 24th, supported by British troops. The hand-to-hand fighting was savage, even by WWI standards. In his history, The Great War, Les Carlyon recounted how the Australians were “enlivened by the omen” of attacking on Anzac Day. Sergeant Jimmy Downing of the 57th Battalion, one of Elliott’s, said the Diggers “killed and killed” in a blood lust.

Another stretcher-bearer quoted in Carlyon’s book, David Whinfield, jotted in his diary: “It is a terrible time. How will men hang on at this awful cruelty. Nerves are being shredded. Men’s future is being heavily drawn from. My nerve is weak.”

The saying popularised by John F. Kennedy about victory — it has 1000 fathers — was never truer than at Villers-Bretonneux. Some say that the Australians’ role in halting the Germans has been exaggerated; that by the time they arrived, British troops had taken the sting out of Operation Michael, and the offensive was spluttering to a halt, dooming the German war effort.

As far as Noel Casey is concerned, it’s a moot point. He approached The Weekend Australian to share his father’s story — the diary has never been seen outside the family — because he thought one man’s war mattered, all these years later, as we look back with awe and bewilderment at what Australia’s Great War generation achieved and endured. A new nation, barely five million strong, sent 324,000 volunteers overseas to fight — and two-thirds of them became casualties: 61,000 killed, another 155,000 wounded.

“Reading the diary, I gained an appreciation and a hell of a lot of respect for what he went through …. when you stand back and look at it, it’s an amazing story. I don’t know how he survived,” Mr Casey said.

After Villers-Bretonneux, his father stayed in the frontline, cycling in and out of Amiens. There were always more wounded men to bring in as the Australians took the fight to the Germans and many more near misses for the young stretcher-bearer.

On August 14, he was taken prisoner at Framerville during the Battle of Amiens, the start of the long pursuit of the Germans to the Hindenburg line. After being questioned and searched — as usual, Private Casey was not carrying a weapon — he was released.

But that was far from the end of the drama. Approaching the Australian lines, he was nearly shot by a nervous sentry. “Plenty of work. Very tired,” he scribbled.

Two days later, he was given “splendid” news: his leave had come through and he was off to England. Private Casey didn’t know it then, but his war was over. He was kept there to prepare wounded Australian soldiers for the long journey home by sea.

“Great joy,” he wrote on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout