Your blood pressure reading is probably wrong

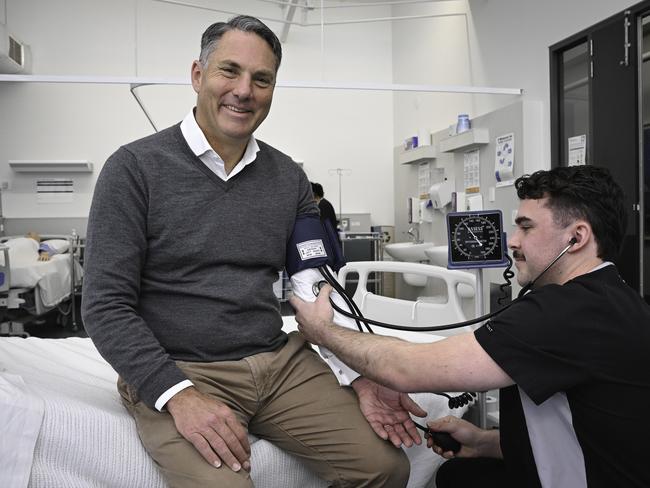

Dangling your arm, wearing the wrong size cuff and scrolling on your phone can make a reading higher or lower than it should be.

Your blood-pressure reading probably isn’t as accurate as you think.

More often than not, patients and even nurses and doctors are skipping steps that help paint an accurate portrait of someone’s blood pressure.

How someone sits and positions their arm, whether they just had a cup of coffee or chitchat with their practitioner during the measurement, and other factors can produce readings that are higher or lower than normal blood pressure.

“To really make a dent at improving people’s cardiovascular health, we need to screen and treat people for hypertension, but we need to do it correctly,” said Dr Tammy Brady, a pediatric nephrologist at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Centre in Baltimore who studies blood-pressure measurement and cardiovascular health in children and adults.

Getting the right reading is important for preventing heart attacks, strokes and other potentially fatal conditions.

What does it take to get your reading right? You should sit with both feet on the ground, legs uncrossed, back straight and your arm supported on a table or other surface, according to guidelines from the American Heart Association and other organisations. A cuff should be positioned over your bare arm at the level of your heart. You shouldn’t talk or scroll on your phone while it is being measured, and your bladder should be empty. And you should take your blood pressure at least a couple of times in a sitting.

Anxiety can also be a factor when it comes to inaccurate blood-pressure readings. Some people have elevated blood pressure in a doctor’s office, though it typically reads normal at home, a condition known as white-coat hypertension.

A blood-pressure reading indicates the pressure of blood pushing against artery walls when the heart beats (systolic) and relaxes (diastolic). It fluctuates with exercise and other activities. The goal is to capture a person’s usual blood pressure over time, without those fluctuations.

High blood pressure, or hypertension, is the leading risk factor for premature death and disability worldwide. Nearly half of US adults have high blood pressure and 20 per cent have it under control, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Left uncontrolled, it can lead to heart attacks, strokes, chronic kidney disease, heart failure and dementia, said Dr Michael Rakotz, group vice president for improving health outcomes at the American Medical Association.

James Young II found out he was measuring his blood pressure wrong, a realisation that potentially saved his life.

At the age of 40, he developed shortness of breath and headaches. He started checking his numbers at home, which were abnormal but not worrisome, he thought. A doctor’s appointment led him to a surprising discovery: his blood pressure was dangerously high.

What had gone wrong? He had the wrong cuff size, and the blood-pressure device was old, Young learned. He was diagnosed with congestive heart failure and other conditions. “I was really playing Russian roulette with my life,” he said.

The diagnosis inspired Young to make changes. He started eating healthier and exercising, which led to improvement in his health. Now 53, he holds a master’s degree in public health and works as a clinical-research retention co-ordinator at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Taking blood pressure inaccurately can often produce a reading that is too high rather than too low. Resting an arm in a lap over-estimated the systolic reading by 3.9 millimetres of mercury, a measure of arterial pressure, and diastolic reading by 4 mmHg, in a study of 133 adults published by Brady and colleagues in October. Blood pressures taken on a dangling arm were even higher. A 2023 study, also by Brady and colleagues, found that a cuff that is too small made blood pressure readings high, while a cuff too large made readings low. (Brady carries a measuring tape in her pocket to check her patients’ arm circumference).

Even small errors in blood-pressure measurement likely affect how millions of Americans are diagnosed and treated, said Paul Muntner, visiting professor of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “We wouldn’t tolerate this when they measure your cholesterol levels, or your A1C levels for diabetes,” he said.

Patients with readings that are higher than their normal blood pressure can end up on medications they don’t need, said Dr Jennifer Cluett, a primary-care provider and hypertension specialist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. That can drop their blood pressure too low, and they can experience symptoms such as fatigue, light-headedness and dizziness, she said. It can even increase the risk of falls or other injuries.

“It’s about making sure that you’re appropriately treating the patient in front of you, making sure they’re not getting more medicine than they need or less than they need,” she said.

A 2017 study by Rakotz and colleagues found that only one out of 159 medical students from 37 states took blood pressure accurately. On average, the students correctly performed 4.1 out of 11 steps to measure blood pressure, including making sure arms and legs were in the right positions. The findings helped to inspire professional groups and medical schools to educate their peers and patients more actively about how to measure blood pressure properly, Rakotz said.

Taking blood pressure properly can take about 10 minutes, hypertension specialists say, but medical staff are often busy and medical appointments can run short. Few exam rooms are set up with a chair for patients next to a desk where they can support their arm, said Barbara Wise, a professor of graduate nursing at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, Indiana. Many rooms have a blood-pressure device attached to the wall next to an exam table.

“I haven’t seen anybody take a blood pressure with a patient’s arm on a table in years,” said Wise, a nurse practitioner who makes site visits around her state. “There’s just nowhere to do it.”

Doctors and nurses do find ways to support a patient’s arm in such exam rooms. Sometimes chairs have wide arms that are stable enough to support a patient’s arm, Cluett said. Some exam tables are adjustable and can be lowered to hold an arm while the patient sits in a chair.

If there are no such options, the doctor or nurse can hold a patient’s arm up, Wise said. But getting the patient to really relax the arm for an accurate measurement while it is being held can be difficult, she said.

The AMA has worked with physicians, care teams and community health centres to make more chairs available next to tables or with suitable armrests, Rakotz said.

More people also take their blood pressures at home, but don’t always receive or follow instructions about how to do it properly. Nearly 80 per cent of blood-pressure devices sold on the internet haven’t been validated as accurate, according to a 2023 study. The AMA has a list of validated devices.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout