What it’s like to get diagnosed with T1 diabetes in your early 20s

At first, I got sick and started shedding weight. I was constantly dehydrated. They were telltale symptoms of an undiagnosed diabetic, but I thought that only happened to kids.

When I was younger I used to love pigging out on those pharmacy jelly beans. I’d hazard a guess most people know them, with their distinctive blue-with-a-yellow-cross packaging. Now, I rely on them to stay alive.

Same pandemic, different illness

I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when I was 23, in early 2021. My pandemic was a strange one. I broke up with my then-girlfriend in January 2020 and before long was moving from Melbourne back to the family farm in Gippsland when Victoria went into lockdown.

In just a year I experienced two breakups: one with said girlfriend, the other with my pancreas.

For the uninitiated, there are two types of diabetes, helpfully labelled type 1 and type 2. T2 mostly comes in someone’s mid-to-later years as a result of good living, is more common, and generally more easily treatable.

T1 is a tricky bastard. It requires daily thought, care and management, sometimes by the minute.

This is a disease which makes you inject yourself, check your blood and watch what you eat every day, with a prognosis of everything getting harder to manage as you age. It almost always feels like you’ve been dealt a losing hand.

T1 diabetes certainly isn’t as intense as cancer or any number of other illnesses, but the way it constantly stays in the back of your mind is tiring to the point of noncompliance with good practice.

Being a T1 diabetic means your pancreas has stopped working. Your pancreas supplies your body with insulin — which carries glucose (sugars) to your cells for energy. Without insulin, your body, desperate for energy, attacks your fats.

When this happens and your fats are broken down, you can lose a lot of weight and have your blood become acidotic, which if left untreated will ruin organs, nerves, you name it, and can result in death.

‘The story’

In the middle of 2020 I got sick and started shedding weight. By the end of the year I was down to 61kg. I’m a taller bloke and usually sit in the mid-80s so something was obviously up. I was gaunt.

I was urinating non-stop (one night-time accident later and I still haven’t bought a replacement electric blanket four years after the fact) and was constantly dehydrated. They were telltale symptoms of an undiagnosed diabetic, but I thought that only happened to kids.

(In the year I was diagnosed, 2021, the age strata with the highest number of T1 diagnoses was people aged 10-14, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. But, while my situation is uncommon, it’s not unheard of. There were more than 1.3 million Australians living with diabetes that year, according to the AIHW.)

I did everything in my power to explain my condition away, telling my increasingly alarmed parents it was probably “lockdown stress” or some other bullshit. Call it rural faith or plain pigheadedness, but I was convinced the ship would right itself.

In January 2021, after months of watching their son waste away thanks to his stupidity, my parents finally convinced me to go to the GP.

The doctor did his own testing, and when re-entering his consulting room — with perfect comic delivery — deadpanned: “Yep, you’ve definitely got diabetes.”

Well, there you go.

The doctor said I needed to go to hospital immediately. I replied with a “no worries”, promising I’d drive myself over at once. “No shot,” he said. “The ambulance is already on its way.”

He was surprised I hadn’t dropped yet, I’d left it so long.

That whole ambulance trip, me hooked up to a saline drip and with two lovely nurses who — in classic small-town fashion — knew my parents, was one of the most serene moments of my life.

The relief of finally knowing what was going on was remarkable.

I took that stay in the hospital in stride, impressing myself with my resolve, learning everything there was to know about my condition and daily management. It was going to be a cinch.

Every. day.

For fear of belabouring the point, T1 management simply never stops. When diagnosed, I knew the basics: stay away from sugary stuff, eat some jelly beans when your sugars are low. But, carbohydrates become sugars in your system, and I didn’t know this.

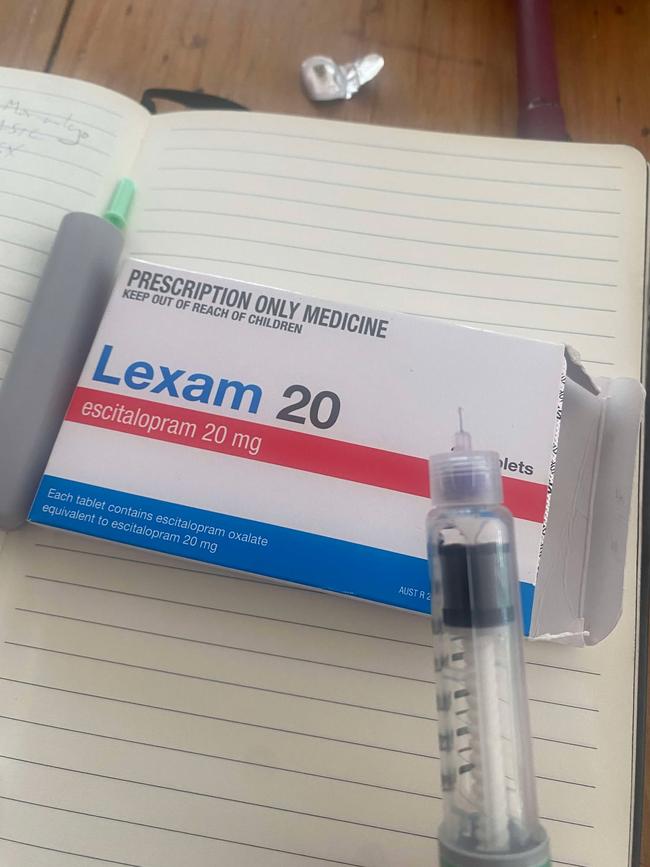

Bedrocks of my diet such as bread, pasta and rice now had to be eaten in moderation, taken in unison with the appropriate amount of injected synthetic insulin in the name of good management. The needles aren’t big, but they can hurt, and you have to rotate injecting sites (stomach, upper thighs, buttocks) so you don’t damage your skin and underlying tissue. It makes eating more of a hassle than it already is, and I’m a terrible cook.

And, as a result of injecting too much insulin or any number of other factors, if your blood sugar goes too low (hypoglycaemia) you need to immediately eat or drink something sugary to stay upright.

People with low blood sugar get extremely irritable. I said some things to my mother I wish I hadn’t during my first hypos; thankfully she took it well.

People are, on the whole, fantastic when it comes to accepting me as a diabetic. I don’t hide it from anyone, there’s never been anything for me to feel shame about, and I have good friends, a fantastic family and a partner whose support and understanding has gone above and beyond what I would ever have expected for myself — diabetic or not — over the past year and a bit.

It’s tough out here

That said, there remain little indignities I experience out and about which are embarrassing, even though I like to think I take personal issues pretty lightly.

I can’t count the times a friendly face has yelled “Oh, stop doing drugs!” or “junkie!” as a joke when I inject myself at the table. Har har.

And, I’ve met my least favourite nurse of all time. Before appointments with my specialist I have to get blood and urine tests done, and my local pathology place in Melbourne’s inner north is set, oddly, within an optometrist on Clifton Hill’s main drag.

The resident nurse, who already is no raconteur, makes me leave urine samples outside her office door, in the middle of the optometrist’s showroom where people are trying on glasses. Once I opened her door to leave it in her office and she yelled at me to leave it outside. Now, I scramble out of there before people get back to 20/20 and see I’ve left a jar of piss in front of them.

Recently, fed up with my nemesis, I went to another nurse, where she took three goes with the needle to find the vein. It’s a trade-off I’m willing to make.

Diabetes Australia says 50 per cent of diabetics experience mental health issues, and it’s not hard to see why.

My mental health issues as a result of my condition can sometimes feel gargantuan. It can make one feel as useful as a lollipop lady without her stop sign. Drive on through.

I developed pretty significant hypochondria in the months after coming out of hospital, with my first panic attack coming as a result of a blood nose. All of a sudden, I was convinced I was going to die.

Before long, whenever something felt strange or wrong with my body — real or imagined — I would have another panic attack. My brain didn’t trust my body anymore.

After a while I had no choice but to start taking antidepressants, and still do to this day, although I’m slowly weaning myself off them.

Antidepressants are tough to evaluate, because they certainly take the edge off. But, they take the edge off everything.

I very, very rarely have panic attacks these days, but the side-effects are tough. Sex, for one, is an activity with less... finality when taking antidepressants.

Long-term as a diabetic, it’s all about watching your extremities. If poorly managed, a diabetic can suffer nerve damage. So, a cut on your foot you don’t feel or notice becomes an abscess, then it’s gangrenous and bang you’ve lost a foot.

And your eyes can start going as well. My yearly optometrist appointments (same place, less urine in showrooms) have been going very well so far.

The bright side?

I promise I’m a positive person. But, I have to take my condition as it comes, day-by-day., and some days are worse than others.

I poke fun at myself, I’ve tattooed an outline of my blood sugar sensor on my arm and always put the actual sensor in the wrong spot. One of my strongest-held beliefs is a certain lightness and brevity of despair is key to managing a long-term condition like this. So far, so good.

I refuse to feel like a traitor to my own body every time I want a Kit-Kat; nine times out of 10 I restrain myself. But sometimes you have to choose to go all in and just get what you want, even when holding a losing hand.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout