The next status symbol? Immortality

The old question of if you were given a box containing the exact date of your death, would you open it has now become: how much are you prepared to pay for the privilege?

If you were given a box containing the exact date of your death, would you open it?

It’s this question author Nikki Erlick explores in her 2022 novel The Measure, in which every adult on Earth receives a chest containing a piece of string indicating the length of time they have left to live. Those brave enough to open it are forced to confront not only their own mortality, but the social and moral consequences that arise with the knowledge of their lifespan and how it compares with those of others.

The premise might sound far-fetched, but excluding traffic accidents, suicide and natural disasters, the medical world’s ability to determine not when, but what, is most likely to kill us is becoming increasingly accurate.

Unlike the protagonists of Erlick’s book, however, our access to Pandora’s box of health knowledge is not based on whether we’re simply willing to open it, but how much we’re prepared to pay for the privilege to do so. According to sociologist Paul Blumberg, for something to be considered a “status symbol”, it must satisfy two conditions, desirability and scarcity. It’s no wonder then that in the United States – a country in which, according to the Commonwealth Fund 2023 International Health Policy Survey, a third of highincome earners forewent medicine or a medical test in the past year because of a cost-related issue – health has become the ultimate measure of wealth. The wellness industry, once dominated by designer yoga brands and organic snack companies, has now become tech’s trillion-dollar baby as companies invest in finding ways to stop the ageing process and restore our youth.

While Musk and Branson race to space, US biotech entrepreneurs such as Bryan Johnson (whose health regimen reportedly costs $US2 million a year) and OpenAI’s Sam Altman are throwing their support behind the quest for immortality, particularly in the area of preventative wellness and cellular anti-ageing. Science is yet to discover a surefire way to significantly extend the average human’s life expectancy, but those with both determination and financial means are going to great lengths to add as many years to their life using the treatments and technologies at hand until it has.

‘I’m scared every time and I always say ‘Please, God, don’t let there be anything, like I’ve got little kids; I don’t want to be facing this.’’

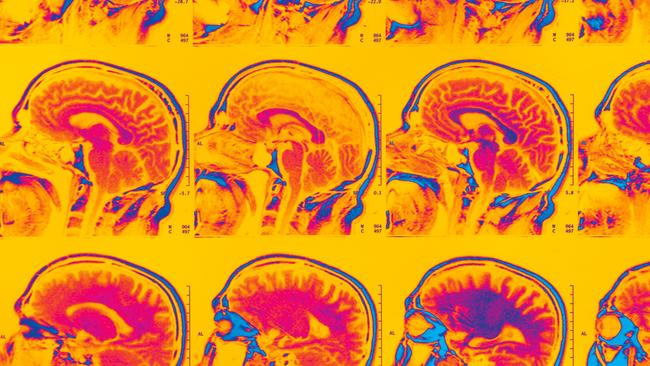

Thanks to the endorsement of celebrities such as Kim Kardashian and Miranda Kerr, a selfie posted from the inside of a privately funded MRI scan is now the health equivalent to flaunting a luxury fashion purchase. At Prenuvo (the Kardashian clan’s go-to for MRIs), the most popular screening option is its “whole body scan”. For $US2499, you can be screened for more than 500 health conditions including multiple sclerosis, fatty liver disease, brain tumours and uterine cancer. But deciding whether to open the proverbial longevity box or live in blissful ignorance of our potential health trajectory isn’t just a dilemma faced by characters in fiction novels.

After the birth of her first child in 2015, talent director Lauren Karan discovered her family carried a faulty SDHB gene, which dramatically increases a person’s likelihood of developing paragangliomas (tumours of the nervous system) and other malignancies. Despite feeling completely healthy, the Karana Downs, Queensland resident decided to get tested. “When I found out I had the gene, I instantly felt like I wasn’t immortal anymore,” the 37-year-old tells WISH. “And I know that’s really weird, because I’d just had a child, and you never think about not being around forever for your kids.” Her familial predisposition meant that Karan’s investigations were partly funded under the federal government’s Medicare Benefits Scheme, which last year added full body MRI imaging to its list of subsidised scans. But under Australia’s diagnostic model of healthcare, hypervigilant, otherwise healthy people with no predisposition to certain cancers or conditions are unlikely to receive a rebate, let alone get a GP referral, for a preventative MRI scan.

While services offered by private companies such as Prenuvo have been deemed unnecessary and even harmful by some members of the mainstream medical community because of the possibility of false positives and the risk of undergoing unnecessary treatment, it hasn’t stopped their growth in popularity.

For Dr David Badov, medical director of Melbourne preventative medical clinic HealthScreen, identifying issues before they become symptomatic can have profound positive implications for a person’s life expectancy. “Unfortunately there are very few of us who die of ‘old age’,” Badov says. “It is usually heart disease, stroke or cancer that cuts our lives short. “So if we can screen, pick up these conditions much earlier and implement changes, then this will change the individual’s life expectancy.” He cites “first stage lung cancers, kidney and thyroid cancers, brain aneurysms, and many other potential ‘time bombs’,” as some of the early stage, asymptomatic diseases picked up during the clinic’s extensive screening program, which Badov describes as a “one-stop shop”.

An initial assessment, which costs $2950 and includes consultations with physicians and advanced investigations such as a skin cancer check, ECG, blood tests and advanced imaging, can take about four hours. At the two-week follow-up appointment, patients will also be talked through the results of genetic tests (“for 147 genes involved in heart disease and cancer”), a sleep study, biological age test, respiratory function tests and mental health assessment, which Badov explains “will provide a comprehensive and holistic assessment” of a patient’s overall health. And on occasion these investigations do reveal something sinister. “It is psychologically difficult both on the practitioner as well as obviously the patient,” Badov says.

But the upside to early detection of an illness is the likelihood that it can be more easily treated, something the Centaurus HealthCare executive chairman says can make it “easier to put a positive spin on”. Though less exhaustive, Dr Adam Brown’s luxurious clinic in Sydney’s east also offers a longevity plan for his wealthy, health-conscious clients who like their evidence-based medicine served with a side of biohacking (and cosmetic injectables for those inclined). “I’ve been on the traditional side of [general practice], which I still do a bit of,” says Brown, a devotee of Australian ageing expert David Sinclair, a genetics professor at Harvard Medical School.

Brown describes his Double Bay practice as “a bit beyond” the domain of a typical GP and cites the “five tactical domains” – diet, sleep, exercise, mental health and medicine/supplementation – as crucial to his patients’ optimal health. In an initial assessment, Brown starts with a detailed medical history and a look into a patient’s disease risk factors. “Then we might do examinations such as body fat percentage – things you wouldn’t normally do in a regular clinic – and then we may send a patient for blood tests, and certain genetic tests targeting specific things such as dementia and heart disease.” After that,” he continues, “we start to discuss the supplement side of things. “These are currently what the longevity experts are recommending to take,” he explains, listing off polyphenols resveratrol and fisetin, nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), quercetin, spermidine (a polyamine for efficient cell renewal), alpha-lipoic acid and vitamins K2, B6, B12 and D3. Brown now recommends these to patients as part of the clinic’s longevity treatment plan. “It’s not about trying to live to 200 years old,” Brown explains, “but rather increasing your health span and having a better quality of life into old age.”

Badov believes we are going to see “more and more” preventative tests such as genetic screening used in the future as people take a more proactive approach to their wellbeing. “The implications of course are that one has to be prepared for the consequences of such potentially positive genetic tests, and ramifications for the future, and therefore it is important that appropriate counselling is provided before the test is performed,” he says. Today, Karan is scanned for tumours every two years and has annual blood tests to check for SDHB-related malignancies.

“I’m scared every time and I always say ‘Please, God, don’t let there be anything, like I’ve got little kids; I don’t want to be facing this’,” she admits. But given the chance, she would “open the box”, every time. “Yes, yes, I would want to know, because it means I can be proactive with my health,” she says. “I can see what’s going on before it comes. And it means I can catch things early that we might not even have known that I have.”

This story appears in the February issue of WISH Magazine, on sale Friday February 2 inside The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout