How Neil O’Riordan helped his partner die

Neil O’Riordan helped his beloved partner Penny die on a Thursday because ‘it’s a s--t night on TV’.

The first time Penelope Blume asked her partner to help end her life, they were in the bathroom of their Canberra home. It was spring last year, and Blume’s 68-year-old body was being progressively consumed by motor neurone disease, her left hand no longer functioning, her legs barely able to carry her even with the help of a walker.

“She was sitting in the chair and I was drying her feet, and she looked at me and she said, ‘Will you help me end my life?’” says Neil O’Riordan. A forthright and mostly stoic man, he recounts this moment tearfully, apologising as he stops to grab a tissue. “Did it take me by surprise? I think we had always operated on the understanding that one of us would help the other. But that was the first time it was real, solid, This is actually going to happen. I cried and I hugged her and I said, ‘Of course’.”

In December, as other people’s thoughts turned to a season of festivities and the emergence of a new year, she asked him again. Hoping to pin down a date, an increasingly frail Blume was wary of her looming birthday, for which she was determined not to be alive. “I thought she was making the decision from a sad place and I thought she wasn’t ready. I wanted her to be more calm in her head when she made the decision,” says O’Riordan, who convinced her to live a little longer. “Both of us knew we were going to do this. But that wasn’t the time. And I probably wasn’t ready either.”

The last time she raised the subject was in March. With her respiratory system waning, and facing the real possibility of asphyxiation, she had become mostly housebound and slept on a mechanised bed in a room filled with flowers. A few evenings later, after sharing some oysters and champagne, she and O’Riordan watched TV, slept briefly, and at 1.30am she woke and declared that the time was right. In the opening hours of Friday, March 15, with her loving partner clasping her hand, Blume died. And that night, O’Riordan, who had dedicated the previous 14 months to her care, marked the start of an intense period of grief — locked up in a police cell.

“She was always more grown up than me.” Aftermore than 25 years of intimate acquaintance, Neil O’Riordan has many ways to describe his long-term partner, her dry humour and the joy she derived from travelling and good food. But the most revealing details are about the strength of her character. “She was always a much calmer person than me,” says O’Riordan, 63, at the kitchen table of their suburban Canberra home, a 1960s red brick building with views to the surrounding bush. “I think that’s why the relationship endured. I was flighty and ratty and all over the place, and she was a much more centred person. And eventually that rubbed off on me.”

Their relationship was long but it also had patches when it seemed it might not endure. Their first meeting was in the late 1970s. Raised in Singleton in NSW’s Hunter Valley, O’Riordan had spent a year at the Newcastle steelworks before training as a psychiatric nurse. One of his colleagues at the Morisset psychiatric hospital was Blume’s then husband. Through several social encounters, O’Riordan’s earliest memories of the woman who would become his long-term partner were not favourable. “We didn’t much care for one another,” he laughs now of his initial reaction. “She thought that I was a country bumpkin and I thought she was a stuck-up bitch.” The daughter of stock and station agents, Blume had attended a private girls’ school in Melbourne and then art school before training as a psychiatric nurse. At 28, she seemed incredibly grown up in O’Riordan’s 21-year-old eyes. “That was part of the intimidation, I think.”

In 1982 he moved to Canberra to further his nursing career. She moved there in the late ’80s after she had separated from her husband, and met O’Riordan again through a mutual friend at his share house. “We were both much older, different,” he says. “Initially Penny was more active about pursuing a relationship than I was. I’m not very good at relationships.”

O’Riordan had been in several pairings by his late 20s and this one did not last either. “We weren’t getting along very well and it was easier for me to leave,” he says of their eventual split. He entered a different relationship, and became a father in 1990 — but by 1994 he and Blume (who did not have children) were together again.

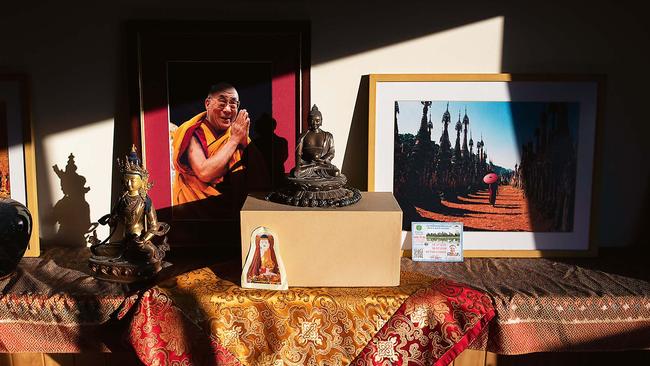

Back in Canberra, they continued nursing and formed a small but valued circle of friends. She enjoyed entertaining and cooked well, but in a mess, while he took care of most other household chores. Buoyed by her increasing interest in Buddhism, as a couple they were unmaterialistic, fairly cavalier with money, and neither suffered fools. “In our lives we got dudded a couple of times by people. But we had made a choice; we didn’t want to be in a world where our first instinct when meeting new people was one of mistrust.” They also liked travelling but never en masse. “We don’t do cruises, even a dinner cruise,” O’Riordan declares, unintentionally still referring to his relationship with Blume, as he often does, in the present tense. At the start of the millennium, the couple began the first of two decades of travelling, taking regular trips of a month to six weeks. By 2015 they were living in Bangkok; with rent at just $1000 a year, they signed a lease for six years. “It had been our intention to die overseas,” says O’Riordan, “to be settled enough, and we were just starting to get to the sort of life we had hoped we might get in Thailand, mixing with locals.” And then a shoulder complaint that Blume had lived with for years suddenly seemed to worsen.

In August 2016, preliminary tests showed that clusters of Blume’s nerves were dying. Further tests revealed advanced motor neurone disease, for which there is not yet a cure, and only one drug that can delay the disease’s progress by up to six months. In her mid-60s, Blume could expect to live just a few years more.

As nurses, she and O’Riordan knew how the disease progressed. “It’s a slowish road to death,” says O’Riordan, who, at a meeting with a treating doctor in Bangkok, revealed that Blume had told him she wanted to travel to Switzerland. He assumed the doctor realised this was shorthand for legal euthanasia at a clinic there at a time of her choosing. “Thai doctors don’t understand that. ‘Yes, go on a holiday,’ he said. So I explained what ‘going to Switzerland’ means. Thais don’t believe in that; it’s not a Buddhist thing.”

Blume, despite her own strong attraction to Buddhism, saw no conflict, and they decided to remain in Bangkok for as long as they could. That turned out to be another year, during which they still managed to travel. “I have a photograph of Penny at Angkor Wat [in Cambodia] in a walking frame and she just looks old and frail. But when you’re with her you don’t see it.”

Eventually the rough-hewn streets became too tricky to manoeuvre even with a walker, and when she could no longer use the stairs of their home in Bangkok, they packed up their stuff and in mid-2018 moved back to Canberra.

While Blume was researching end-of-life possibilities, her initial thoughts about dying in Switzerland — or Victoria, where assisted dying laws for the terminally ill had recently been passed and where she had managed to have herself placed on the electoral roll — ebbed. “Suddenly some things became important,” says O’Riordan. “I think home became more important. When she was well she never thought of this [Canberra house] as home.” In the years they had been together, she had never discussed her grandparents’ final resting places. Now she insisted on visiting their graves in Gunning, an hour’s drive north of Canberra, several times. And despite her earlier thoughts, she wanted to die at home.

With her limbs increasingly failing, she became uncharacteristically anxious. She stopped talking to friends on the phone, and became quieter. “Some of it I think was distancing herself emotionally from people, getting ready for death. It must take a real focus to be able to narrow it down to a date and time,” says O’Riordan, and he grips his head in his hands.

As 2019 neared, Blume “seemed resigned, matter-of-fact, death is death; pissed off about it, but it is what it is”, says Kerri Neve, who had been a close friend since meeting her at work in 2002. Like many of those to whom Blume was closest, Neve figured that her tolerant, rottweiler-loving friend would have her own views on the end of her life. “We were both country girls,” she says. “Both of us would have grown up with the view that if you’ve got a sick animal, just put it down.” But she had no idea what plans, if any, her friend had made.

“I think all of our social circle knew from our conversations over the years that this was our intention; that we were not going to go to nursing homes,” says O’Riordan. With Blume’s condition worsening, her friends assumed she would choose to end her life. But as to when and how, “other than Penny having a date in her mind, nobody else knew”.

As he morphed from employed nurse into full-time carer, O’Riordan’s life with Blume became an intense, loving bubble. “I didn’t open mail for 14 months; I wasn’t interested in the outside world. I simply didn’t care,” he says. “Penny used to say to me, ‘Why don’t you get the carer people to come here?’ And I would say, ‘Why?’” He knew how to care for her and would do so, essentially alone, until she died. “My time as a full-time carer was always going to be quite limited. It’s a special kind of privilege to be able to physically care for someone as well as emotionally care for them.”

By March this year, Blume’s vitality had dimmed. For months she had fought for her independence, struggling to dress, wash and feed herself with her right arm, the last of her limbs still barely functioning, and now her respiratory system was affected. Over several months, she had been accumulating the material she would use to end her life painlessly, from a supermarket and online. As March progressed, O’Riordan, who had modified one of the items for her, secretly hoped that some of the material would have become unusable.

She tried again to set a date. “I said, ‘You need to tell me because I will never be as ready as you are’,” O’Riordan recalls. Her birthday was on March 23, and a few weeks prior she picked a weekend. When her brother decided he would visit again, she decided to wait. When he deferred his visit, her mind seemed set.

“Why don’t we do it now?” Blume suggested late one week. O’Riordan stalled; he needed a few more days to get his head around the idea. Although he had agreed to help her, and did not want her to die alone, no day seemed right: Friday was too soon, so was Saturday. And Sunday. “She’s gone, ‘Monday?’ I’ve said, ‘Jeez, you know you’ve been watching My Kitchen Rules; you might want to see if those blokes get kicked off. Thursday is a shit night on TV.’” She laughed. “So we chose Thursday.”

“I’m really good at procrastinating, so Wednesday was like usual,” says O’Riordan, who bought flowers to decorate Blume’s room that day. The following morning he arose early to buy some fresh seafood for dinner, the day’s magnitude still to fully settle on him. “Up until the event it was an abstract concept,” he says.

Late on Thursday they shared the seafood. They hugged. And even when she woke in the dead of night for her final hour, he tried to be practical. “I did get into a bit of a matter-of-fact mode. There’s a bit of me going, ‘You have just got to keep your shit together because this is not about you’. And she is being calm and coherent about the whole arrangement.”

In the end, after all their years together, there was no grand finale. “What was there to say? There’s probably a lot of stuff we could have said to one another, but I think we just lived it out rather than said it. ‘I love you’? ‘Goodbye’? I don’t even remember saying that.” What he does remember is that she was half sitting up in bed, in her pyjamas, and he was sitting beside her, holding her hand as she looked at him. She died instantly. “It was as advertised,” he says quietly.

“I just let out this huge wail. And I was sort of messy and emotional and I thought, just check and make sure. And then I removed everything.” Tossing into the bin some of the material she had used to end her life just days before her 69th birthday — “I didn’t want to see her like that and I didn’t want anybody else to see her like that” — he was shrouded in grief. “And me and the cat stood at the bedroom door for about half an hour just looking in.” Around 4am he fell asleep briefly in the lounge room; by then he had been up for almost 24 hours.

The sun rose on the first day of his life without Blume. He phoned her doctor to report she had died. “And he said, ‘It’s a bit sudden. I have to call the coroner.’” Within an hour, the first of more than a dozen police arrived at the house, searching his bins and taking away his computer and mobile phone. “They asked me what happened and I said, ‘I don’t know. I think she died in her sleep.’” On the way back from the bathroom at 4.45am, he said, he had looked in her room and she appeared to have died. “And they said to me, ‘Really?’ And then I told them.”

By 9am he was being driven to Woden police station for a formal interview. But the recording equipment there was not working so he was taken to the station at Civic. “Penny died the night that 51 people got slaughtered in Christchurch. I was in the police car when I heard that and in a weird way it helped, it gave me some perspective,” he says. “We were lucky. We had pretty good lives. And shitty things happen to people all the time.”

He was with the police all day. “They were outstandingly compassionate. I was never made to feel like a criminal. I was always made to feel like somebody who had just lost their wife.” His official interview lasted three and a half hours: Where had he held his partner as she died? Whose bank account had been used to purchase the items used to kill her?

Around 9pm, he was told he would be charged with one count of aiding suicide, and kept overnight, because his home in Thailand made him a flight risk and because of concerns for his welfare, lest he return home and hurt himself. He was fingerprinted and locked up. “As soon as the cell door closed, I ate my sandwich and my apple juice and I went to sleep. I slept like a log.”

The next morning he was handcuffed and led across to court. His matter lasted only minutes. The magistrate released him without bail and let him return home to grieve. “My first thought when I was walking out was that I won’t even get to tell Penny this story.”

When he agreed to help his partner end her life, O’Riordan knew he could face enormous consequences. Under ACT law, anyone who aids or abets a suicide or attempted suicide faces up to 10 years in jail. The territory’s Director of Public Prosecutions, Shane Drumgold, reviewed the case and decided there was a good chance O’Riordan would be found guilty, as he knew of his partner’s plans and had helped modify an implement she had used. But O’Riordan’s actions, Drumgold also concluded, had been “motivated wholly by love and compassion”, and it was not in the public interest to proceed with prosecuting him.

“But for him, the death would still have occurred — but it would have been a much more dramatic death,” Drumgold says from his light-filled Canberra office, only metres from the cell and courthouse where O’Riordan was taken.

In early July, as the case returned to court, the DPP announced that it would not be proceeding with the charge. Four months after Blume’s death, O’Riordan was a free man. “Lots of people do illegal stuff for a good motive. But the fact that he has paid more than anybody for this event is of some significance,” Drumgold says now, stressing that his finding is not a signal for how others might avoid prosecution. Nor is it likely to lead to legislative changes; federal rules prevent the ACT parliament from making euthanasia-related laws.

In Australia, prosecutions for assisting suicide are rare. Few cases result in penalties harsher than a suspended sentence or a good behaviour bond. In the ACT, O’Riordan is one of only two people to have been charged in the past decade — and his case, Drumgold stresses, has some particular circumstances. “Underlining all this is a man who lost everything. There is nobody more affected by this event than him. There is nobody on the planet who wanted this event less than him.” Although relieved at the decision, O’Riordan had been prepared to live with the consequences of his actions. “There is nothing nice about jail,” he reasons, “but given the choice of my life with Penny and the things that we had talked about versus what the law says, it was never a contest.”

Similarly, Blume’s old friend Kerri Neve says the terrible gap that Blume’s death has left in her life is preferable to the alternative. “We had this friendship that was extraordinary, and I certainly wouldn’t have wished for her to be alive one more minute living inside this body that had decided it didn’t want to work for her anymore.”

The circumstances of Blume’s death meant that O’Riordan was alone with his immediate grief. “One of the things you’re denied is the capacity to end your life with family and friends around you… because you are breaking the law it becomes a covert activity.” Does he feel cheated? “No. I got to live with Penny. It’s an emotional housekeeping issue,” he says. “When my mum died there was a bit of humour… we were never going to have that, but what we did have was the time before, and I remember the alive time rather than the dead time.”

Four months on, he is still awaiting an inquest into her death. In the house he now shares with the cat he suspects Blume acquired to keep him company after her death, signs of the life he once had linger. Her bed is carefully made up with a cheery cover, and in another room racks of her clothes await the day he is ready to let them be worn by someone else. In the lounge room, with its smattering of printed throws acquired on their travels, her oversized comfort chair, which he finds too uncomfortable to use, still dominates the space.

“I sometimes think I’ve done a bad thing,” O’Riordan says. “I have participated in somebody dying. And then there’s another part of me that says, what was bad? Bad how? It’s only bad if I put it up against some Christian moral principles. But I have seen enough people die to know that maybe you should get some choice.” He sips his strong black coffee and looks out towards the bush. “I don’t think I have paid too much of a price, except sometimes I am a bit lonely.”

Lifeline 13 11 14; Beyond Blue 1300 224 636

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout