A doctor’s guide to living well

What is a healthy lifestyle and how do I make it a habit? Our resident GP columnist offers a pocket guide to what you should focus on.

What constitutes a healthy lifestyle? Changing habits is not that easy and there is no doubt that work-life imbalance, the use of technology and the convenience of fast food and food delivery contribute to our mostly sedentary lifestyle, which is as toxic to health as smoking.

The epidemic of obesity predisposes people to all types of chronic disease and is largely attributable to these factors, but of all the options, trends and fads spruiked on social media promising a better body and healthier lifestyle, how do you choose a plan and then stick to it long term?

I have conversations with my patients along these lines every day and incorporate key lifestyle messages into our consultations, taking the general approach that change to established habits requires that the interventions be simple, affordable, enjoyable and doable.

In general, patients give more attention to recommendations around lifestyle for disease prevention or just healthier living when they present with or are diagnosed with a more serious condition such as diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer or anything to do with the heart.

Much of this will already sound familiar, and the list includes the Mediterranean diet, regular exercise, social connectedness, good sleep, cessation of smoking and illicit drugs, having a connection with nature, managing stress, having a sense of purpose in life and reduction of exposure to environmental pollutants. Lifestyle is much more than just what you eat and how much exercise you undertake; it’s how you live that incorporates your daily, weekly and even annual patterns of behaviour.

A doctor’s guide to living well

Diet: the Mediterranean reimagined

The Mediterranean diet is one of the most researched for its health benefits, hence its inclusion here. It has evolved somewhat since ancient times but remains predominantly plant-based and continues to include the three original staples: bread, olive oil and wine. It’s mainly a pesco-vegetarian diet, with about 60 per cent of the calories derived from plant-based foods, and includes mainly cereals, vegetables, fruit, limited amounts of meat and milk, daily yoghurt and cheese, game, fish and generous servings of olive oil.

The Mediterranean diet is not just about the food and food types but is an integral part of a lifestyle that encompasses shared food preparation, moderation in portion size and a preference for locally sourced, biodiverse, seasonal products. Eating is not rushed; this is a time for social interaction and conversation.

As a contrast, think about your office tearoom where communal eating usually occurs. There may be an array of cream-filled biscuits, tea bags, instant coffee; some may have an in-house coffee machine. Consider how it might feel if this were replaced with an array of fruit (oranges, bananas, pears and apples will do), frozen berries in the freezer, some plain yoghurt, a jar full of walnuts, honey, some sliced sourdough bread and a tub of Kalamata olives, with a planned communal meal once a week or month.

For many people, olive oil is being priced out of reach because of floods, droughts and interruptions to supply chains from wars in Europe and the Middle East. Buying fresh fish is prohibitively expensive for most and the cheaper, crumbed fish alternative does not confer the same benefits. An affordable substitute is canned sardines in olive oil. For those who cringe at the thought of sardines, try smashing them on to some sourdough bread (toasted or not) or some pasta, add a generous dose of lemon juice, a sprinkle of pepper and some chopped parsley. You can grow the parsley in a window pot by the kitchen sink.

Make a salad out of washed, peppery rocket and finish off this meal with some sliced-up orange and pear or apple to refresh your breath. The vitamin C in the fruit also acts to release the iron and goodness from the meal. The sardine bones are fine enough to chew and swallow and are a terrific source of calcium. Sardines’ brief lifespan in the sea means they hardly contain mercury, unlike more expensive deep-sea fish such as tuna, swordfish, rockling and dory.

If you do this just twice a week you’ll be getting some of the benefits of the omega-3 fatty acids that are so good for the brain and heart, along with all the other added benefits. Store some canned chickpeas, lentils and beans in the pantry to throw into a soup or over a salad and keep a tub of plain yoghurt in the fridge. Eat at least three heaped tablespoons of yoghurt daily with or without a drizzle of honey, some crushed walnuts, oats or seeds. These simple ingredients provide you with the basic Mediterranean diet at minimal effort and cost.

Wine: to be or not to be?

Few people ever broach this topic with their doctor except when being prescribed antibiotics or a new medication. Until recently, the glass of wine a day with the evening meal was enjoyed not only for its taste but for its presumed health benefits. Alcohol is now classified as a toxin and has been associated with increased incidence of cancers and cognitive decline.

In the ancient context, alcohol was part of a non-prescriptive lifestyle and part of the Mediterranean diet, which gave the individual the flexibility to feast, fast and participate in cultural rituals. This was all underpinned by the axiom “Pan metron ariston” – expressed by the ancient Greek father of modern medicine, Hippocrates – which in English simply means moderation in all aspects of life.

My experience has been that advising patients to avoid all alcohol tends to alienate them, so after providing the facts, those who choose to imbibe are recommended to eat at the same time they drink to slow its release. Its toxic effect on the developing baby is emphasised and therefore should be totally avoided, even in the preconception phase.

Exercise: moments of movement

Gym memberships often are not used to their full benefit when you have dependent children, and incorporating exercise into the day, if it is not your favourite thing, seems insurmountable, so I talk about opportunistic “moments of movement” – not hours. My simple practice is to recommend activities for outside, the office and for home.

For outside, it’s brisk walking for up to 30 minutes until you get the “huff and puff” or develop a slight sweat. Fresh air is especially important after being indoors and is invigorating.

For the office, I recommend a series of short exercises that includes wall sits for around 15 seconds, with up to 10 repeats, three times a day. Then I suggest getting in and out of a chair with arms stretched out horizontally in front, with the same number of repetitions. To this I include some basic floor stretches throughout the day, and planks for the prevention of back pain and to strengthen the core muscles. It’s not unusual for me to demonstrate this while talking about it and even reluctant patients occasionally join in with me, which generates laughs.

Investing a few dollars in rubber bands for resistance exercises is simple, and performing stretches of the legs and arms when standing or sitting between activities is encouraged. For home, dance is something I like to recommend and there’s nothing like a disco beat or Latin American music for doing the housework. It gets the heart rate up and is easy and fun.

Generally, people will do bits of easy activity that tick the exercise box and that make them feel better. My guess is that there is some benefit in that compared with not doing these at all and it’s a start in the right direction.

Connections: social circles and spending time in nature.

It’s important to actively arrange to meet up with friends and family members. Our social circles tend to shrink once in the workforce and everyone gets busy with life. If you take the initiative and plan a coffee catch-up, a walk or a regular dinner, you can invite friends to include others over time.

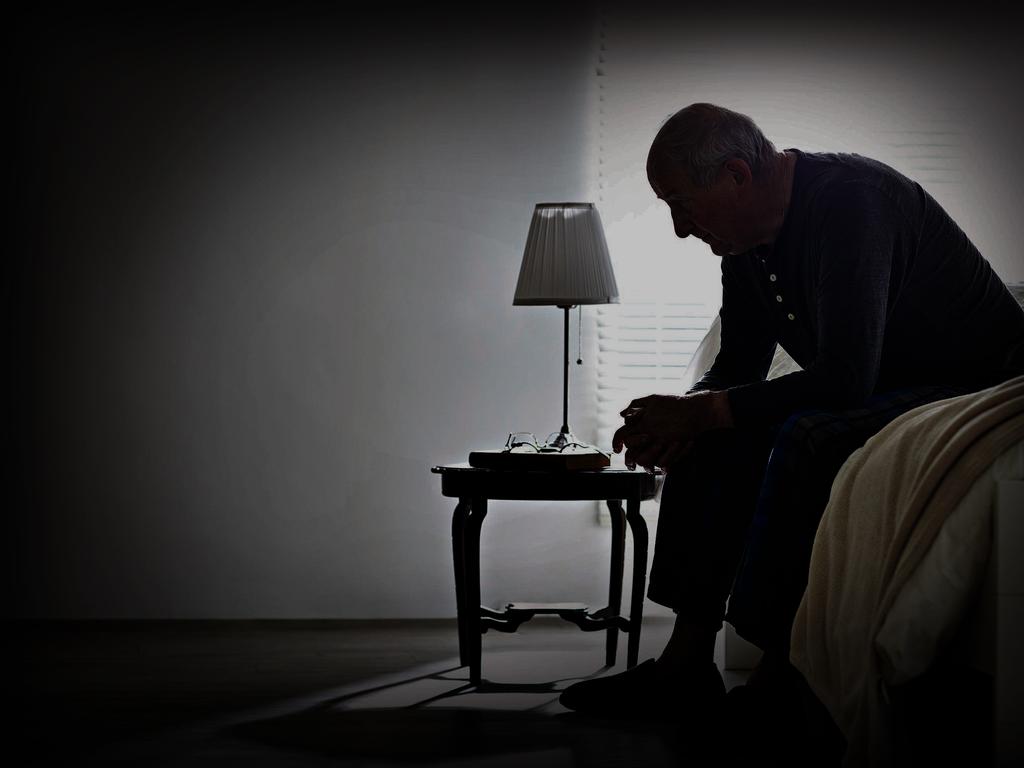

Sadly, one in three Australians reported feeling lonely in the State of the Nation Report 2023, and this affects women and men equally regardless where people live across Australia.

Loneliness is more closely associated with depression than loss of job or low socio-economic status, and the stigma associated with it means that loneliness becomes self-perpetuating because people who feel lonely are less likely to engage in physical exercise, more likely to have social media addictions and are generally less productive at work. Lonely people are twice as likely to develop a chronic disease and nearly five times more prone to depression and anxiety. Solving this problem is a social responsibility.

The not-for-profit Friends for Good group helps workplaces address loneliness and provides support for people who want to check in and talk about loneliness. Breaking the cycle of loneliness can be terrifying as talking about feelings, for many people, doesn’t come naturally. There are meet-ups, volunteer groups, local activities in libraries and community centres, and then there is the phone call to family members and old friends.

We take the incidental social interactions at the local cafe or shops for granted yet this is a form of “social snacking”. These are the conversations we have that are not deep but they provide opportunity to bridge the gaps between the deeper connections that, because of working from home and geographic distance, may be fewer.

If you talk to your general practitioner about loneliness, they will engage in a practice referred to as “social prescribing”, which is similar to the list of recommendations provided by Friends for Good and the Department of Health.

Spending time in nature also can have a positive effect on mental and physical health and wellbeing, as well as alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression, so joining a walking group or just visiting your local park can have beneficial effects. Practising mindfulness, “forest bathing” (walking in forests) and “green prescriptions” (going bush or walking beside the sea) are evidence-based interventions doctors are encouraged to prescribe for loneliness and stress management.

Toxins: reducing exposure

Thinking twice about what we buy, what we eat and what cookware we prepare our food in can reduce our exposure to environmental harms such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals, “forever chemicals”, microplastics and heavy metals. Cancer patients and their partners express particular interest in learning more about toxic pollutants that are invisible but ubiquitous, and more can be accessed in my previous article on this here.

Stress: when yoga is not enough

Managing stress is difficult and the pressure points change with each life stage. Many people need to delay retirement and, because of a combination of societal and personal reasons, are working harder than they ever expected.

Tackling health issues, inheriting more responsibilities and dealing with ageing parents mean you just can’t practice yoga or meditate your way out of deadlines, financial stressors and relationship tensions. Sometimes a talk with a professional counsellor is required. That’s not to say that these practices don’t help with finding space to sort through the chaos, but talking things out does make a difference and a lot of time I find myself listening, then guiding my patients through a series of deep breathing and visualisation exercises. Together we take five deep, slow breaths with our eyes closed while visualising a floating lily on a pond, which leaves us both feeling better. It’s not an answer to real life problems but taking deep breaths several times throughout the day helps provide some clarity and recharges the mind to face what’s next.

Sleep quality

People often ask: “How much sleep should I have?” The answer to that is if you wake up feeling refreshed and do not experience daytime sleepiness, the amount and quality of sleep is probably adequate.

For most people this is about seven to eight hours, and for some it’s about six hours, but this also varies with age and health, as adolescents, children and people convalescing from illness need more sleep. You can assess your own sleep if you have a watch with embedded features or can be referred for formal sleep studies that record brain waves, oxygen saturation, movement and loudness of snoring. If adequate lengths of deep sleep cycles and rapid eye movement cycles are achieved, it’s more than likely you will wake up feeling good.

If you are a snorer, this may or may not affect you as much as your partner, so it is worth seeing your general practitioner to discuss getting this assessed and treated. Good sleep quality is essential for physical and mental health.

Sleep is when our immune system repairs itself, cells regenerate and growth occurs. Brain fog, poor concentration, memory lapses, stress, mood disturbance, increased blood pressure, appetite and hormonal disruption can all be caused by sleep deprivation or poor-quality sleep and across the long term is associated with cognitive decline.

A severe form of sleep disruption occurs because of the condition referred to as obstructive sleep apnoea, which is when the airway becomes obstructed during sleep and compromises oxygen levels in your blood. This is a serious condition that does not go away without some form of management. For overweight individuals, weight loss is recommended as a first line, hence the recent announcement that Mounjaro (tirzepatide) is approved for use in chronic obstructive sleep apnoea.

Some people have upper airway anatomy that closes when lying back, which can improve with surgical trimming to open the airway. Others benefit from wearing a mandibular advancement splint, which is like a custom-made mouthguard that is worn in bed to prevent the jaw from sliding backwards when lying flat. Some people benefit more from having a continuous positive airway pressure machine, which helps keep the airway open while sleeping.

As for napping, anything less than 30 minutes during the day and no later than 3pm can be quite rejuvenating. Limit the daily caffeine intake and try decaffeinated beverages after midday. Sleep hygiene practices include establishing a consistent time for going to bed and waking up that is maintained on weekends, as well as keeping technology and TV out of the bedroom. It’s also important to have nothing to eat for about three hours before going to bed to allow digestion to take place.

Purpose: Finding what you value

Having a sense of purpose in life is associated with lower stress levels and a sense of happiness. Activities that provide this for a person also help build resilience and social networks. Some people derive a sense of purpose from raising children yet down the track, if other interests are not fostered, “empty nesters” can feel a deep sense of grief and even a loss of self-worth when the children leave home. Others experience similar emotions on retirement. Exploring other interests after a full working life and raising a family may feel contrived and uncomfortable initially, but this is where becoming involved in a charity or a community group that aligns with your values, or planting a garden that you can tend, fulfils many of these needs and can have positive health impacts.

Adherence to lifestyle advice is not as easy as it sounds. It is best achieved through a non-judgmental partnership with your general practitioner with planned follow-up visits across time. It’s human to revert to previous habits after the three to six-month mark but incremental changes, across time, do make a difference and should be celebrated.

Magdalena Simonis is a senior honorary research fellow at the University of Melbourne department of general practice and a longstanding member of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ expert committee on quality care.

This column is published for information purposes only. It is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be relied on as a substitute for independent professional advice about your personal health or a medical condition from your doctor or other qualified health professional.

References

- Serra-Majem L., Tomaino L., Dernini S. … Trichopoulou A. Updating the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid towards Sustainability: Focus on Environmental Concerns. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 25;17 (23): 8758. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238758. PMID: 33255721; PMCID: PMC7728084.

- Sidossis, LS, Lawson, R., Aprilakis, … Itsiopoulos, C. (2024), Defining the Traditional Mediterranean Lifestyle: Joint International Consensus Statement. Lifestyle Med., 5: e115.

- Altomare R., Cacciabaudo F., Damiano G., … Lo Monte AI. The Mediterranean diet: a history of health. Iran J Public Health. 2013 May 1;42(5): 449-57. PMID: 23802101; PMCID: PMC3684452.

- Ending Loneliness Together (2023). State of the Nation Report – Social Connection in Australia 2023.

- Friends for Good

- Department of Health Local Connections – a social prescribing initiative

- Health Direct

- Chen H., Meng Z. and Luo J. (2025) Is forest bathing a panacea for mental health problems? A narrative review. Front. Public Health 13:1454992. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1454992

- Brockis J., Flipping the script on loneliness with green prescriptions MJA Insight+, January 13 2025

- Panțiru, I., Ronaldson, A., Sima, N. et al. The impact of gardening on wellbeing, mental health, and quality of life: an umbrella review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 13, 45 (2024).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout