The love triangle that inspired the gourmet guide to sex

For all its hippy aspirations, The Joy of Sex was forged in a tempestuous open marriage. As the director of Bridget Jones prepares to turn it into a comedy, this is the true story.

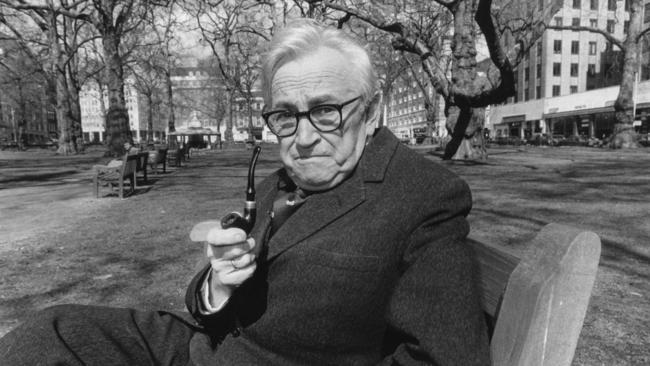

He, according to a newspaper profile in 1963 (the year Philip Larkin claimed that sex began), was “round, compact and apparently stable": a heavily spectacled, club-handed academic addicted to cheap cigars made, he joked, of “lettuce and Kleenex”.

She was his first wife, quiet, undemonstrative and against sex before marriage. The other she – his mistress and second wife – was noisier, randier and an alcoholic. And out of the three of them was born The Joy of Sex, the most famous guide to lovemaking since the Kama Sutra and, it was announced last week, soon to be a feature film from the director of the Bridget Jones movies.

“The irony is that the book was an unashamed sex guide for loving couples, yet it was created out of a somewhat tempestuous triangle,” says Sharon Maguire, the newly named director of The Joy of Sex movie. It will tell the story of Alex Comfort, the 1972 manual’s author, and his life with his first wife, Ruth Harris, and his wife’s former best friend Jane Henderson.

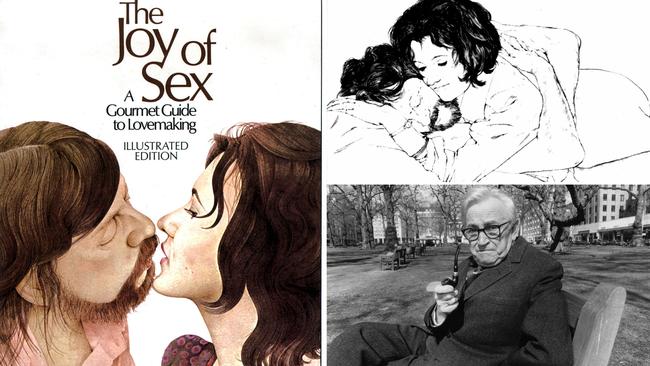

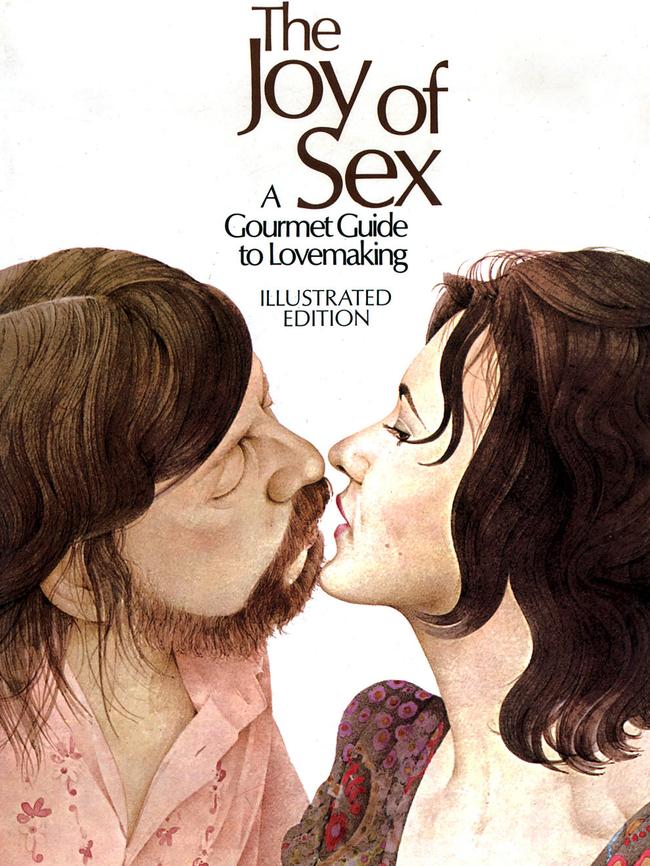

When it was not causing outrage, in its day The Joy of Sex was regarded as serious work by a serious scholar, an act of liberation fit for its socially revolutionary times. It was written, however, in such engagingly unthreatening prose, and the sex acts it described were illustrated by such charmingly inoffensive yet sensuous drawings and watercolours, that it became an immediate international bestseller that has sold more than 12 million copies.

Your no doubt respectable parents may have owned a copy. It was crafted, after all, to resemble a cookbook, which was Comfort’s organisational model, his sexual recipes divvied up between “ingredients”, “appetisers”, “main courses” and “sauces and pickles” such as “blindfolds, chains, harnesses, gags, ropework, hazards and merkins”.

It is a short book but its author was last year scrutinised in a 648-page biography, Polymath, in which Eric Laursen emphasised that Comfort was not just a sexpert but a poet, novelist, biologist, gerontologist and political thinker.

Indeed, in an interview in 1974 Comfort explained that “The Joy of Sex was an expression of my anarchism”, his anarchism being a belief that we all could get by perfectly well without oppressive authority so long as we were kind and respectful to one another – not least in bed.

Speaking from his home in Massachusetts, Laursen explains to me why Joy was revolutionary. In the first place, before then sex manuals were either unreadably scientific or “sleazy and cheesy”; in contrast, Comfort’s book was welcoming, neither judgmental nor prurient.

Second, it promoted the idea that sex was “collaborative": “It was two adults discovering each other’s needs and desires and trying to fulfil them.” The third breakthrough was its insistence that sexual fantasies were neither kinky nor out of bounds: “Alex’s view was that fantasy was a good thing. It’s how adults play sexually, and it should be encouraged.”

The Joy of Sex’s actual content and impact seems, however, to be of less interest to Maguire than its writer’s own sex life. “The story of how Alex Comfort persuaded his wife and her best friend to entertain a ménage a trois for over ten years prior to the book’s publication is a mystery that needs to be unravelled,” she has said. “All I can say is he must have talked an amazing game. Dissecting that triangle lies at the heart of an emotional, moving, funny, controversial and uniquely British story.”

Funny? Well, certainly smutty giggles can be had at the expense of Joy. Its sauces and pickles section, for instance, contains a passage on horses (“Some men also like to dress women up as horses, though they can’t usually be ridden in this manner”). There’s also mention of a “diabolically ingenious gadget” new to the Scandinavian market called a “grope suit”.

The book’s illustrations are also fodder for some detumescent British humour. Originally Comfort presented his publishers with Polaroids of him having sex with his mistress. Studying the blurry shots of the 50-year-old author with just a thumb and a stump of a finger on his left hand (the other digits having been blown off during an experiment with gunpowder he conducted as a 14-year-old), they politely passed.

Instead, the poses were recreated by one of the book’s illustrators, the hirsute Charles Raymond, and his German wife, Edletraud, whose armpits were equally hairy, with another illustrator, Christopher Foss, doing the drawings. The sex was for real but the ambience was not romantic. Conducted during the 1972 miners’ strike in a chilly third-floor flat in Kensington, coitus would be interrupted by power cuts.

And, of course, infidelity can be laughable: ask any Restoration playwright. Conducted, as was Comfort’s, under the Tupperware skies of Seventies Essex and north London, it may indeed look a little ridiculous. Yet Laursen’s account of Comfort’s infidelity is not particularly amusing. Nor was it very polyamorous, even had he wanted it to be.

Sex with multiple partners, Comfort wrote in Joy, was “an important anthropological resource” and one “becoming more easy to arrange”. Yet despite the odd extramarital romance, consummated or unconsummated, there is little evidence of Comfort taking advantage of this option besides a sole night of likely passion in the early Seventies between Comfort, an American academic called Marilyn Yalom and his mistress Henderson.

Safely back in California with her husband, Yalom wrote to them that “in every way it was what I needed”. Perhaps it was what Comfort needed too. Although in his 1963 book Sex in Society he had written that a bit of infidelity could be an “adulterous prop” that kept partners “on their feet”, in reality his love triangle was as stressful as it was satisfying.

He had met Harris at Cambridge, where he studied medicine, and she, three years older than him, was studying to become a social worker. Henderson was her room-mate. Comfort and Harris became an item, in love but perhaps not in lust.

Indeed, he insisted he had no sexual experience until, aged 23, he married her, after a three-year engagement, in 1943. From a similarly middle-class and suburban family as him, she was more straitlaced than Comfort, and less tactile, certainly less tactile than Henderson. They began their affair in 1960, even as his wife was being diagnosed with depression. The two friends were of different types. Unlike Harris, Henderson tended to speak her mind and her liveliness extended to the bedroom of her flat in Kentish Town, north London.

It was, Laursen writes, the beginning of a “sexual voyage of discovery” that would directly lead to The Joy of Sex. Indeed, they kept a log of their lovemaking, entitled, presumably in a nod to DH Lawrence’s John Thomas and Lady Jane, “Our ABC by John and Jane Thomas”.

After a year of assignations, Comfort told his wife he wanted an open marriage. Upset but committed to the respected if controversial thinker who provided for her and their 14-year-old son, she acquiesced. In 1961 Henderson even accompanied the Comforts on a holiday in Ireland, although there is no suggestion the three shared a bed.

The arrangement endured for a dozen years, him spending weekends with his wife in Loughton in Essex and weekdays with Henderson. Theoretically all this was liberating. In practice, Comfort later told an interviewer, the two women “were both erupting the whole time”.

It was Henderson who finally decided Comfort must choose between her and his wife. In the spring of 1973, after nearly 30 years of marriage, he presented her with divorce papers. “Jane needs me more,” he explained: the previous year Henderson had been arrested for being drunk in a public street, spent a night in police cells and been fined pounds 1.

Comfort, however, vowed to his soon-to-be ex-wife that he’d always take care of her and tactfully delayed the British publication of The Joy of Sex until after the divorce, knowing she would be embarrassed by the publicity it generated.

In June that year he wed Henderson. The marriage was not one of Dr Johnson’s triumphs of hope over experience, however. In the Eighties, the couple having moved to California, Henderson became depressed, began drinking heavily and could become “very nasty, explosive, irrational” with their friends.

Comfort was loyal but at a loss. On a trip to London with Comfort in 1984 to scope out a return to Britain, Henderson had a breakdown and was admitted to hospital. Comfort flew back to California, telling his son, “The last thing she needs is me around.”

Settled again in England, Comfort in 1991 suffered a brain haemorrhage, followed by a stroke for which he had lifesaving surgery. Henderson took his illness hard, had a further breakdown and found herself in a hospital ward near to her recovering husband’s.

That November, she was found dead at home in her armchair, killed by a brain haemorrhage at the age of 70. Comfort and Harris, who’d remained in cordial contact by phone, met again over Christmas 1995 at their son’s home. Comfort died aged 80 five years later, Harris four weeks after that.

What you may have noticed from this summary of Laursen’s account is that none of it amounts to what most of us would call a ménage a trois. Although the Oxford English Dictionary defines the term broadly as “an arrangement in which three people share a sexual relationship, typically a domestic situation involving a couple and the lover of one of them”, most people would say a ménage involves a trio living under one roof, if not sharing one bed. Comfort’s arrangements would surely be better described as that of a man with a mistress of whom his wife knew but did not approve. Less amusing.

Yet Laursen detects the seam of comedic potential Maguire intends to mine in her film. “I think she’s on the right track with that. I hope the movie doesn’t turn out to be too broad in the one-liners and pratfalls, but she’s right. And the story of how the book was put together, during the blackouts period, is really quite wonderful.”

Comfort’s son, Nicholas, a journalist now in his late seventies, was 27 when Joy came out and so missed the schoolboy taunts that its notoriety might have inspired. He has been talking to the coming film’s producers since 2017, and it was clear from the start the movie would be a comedy.

“I haven’t seen the treatment,” he tells me from his home in London, choosing his words carefully, “but they have me fully on board, and I hope to have some input when the film is actually made. He was a loving father, and I’ve always appreciated his many good points. Hopefully some of this side of it will rub off on the film.”

Perhaps, if the comedy is done well – and with Maguire on board, why wouldn’t it be? – his father would have been rather amused by any liberties it takes. Comfort was no aficionado of troilism, but he did endorse it. Also, he was not above teasing his readers. The grope suit, he told The New York Times a decade after Joy’s publication, was simply a joke he had made up.

He died on March 27, 2000, on the same day, as it happens, as Ian Dury, writer of that other saga of polyamory Billericay Dickie, about an Essex man who would “rendezvous with Janet/ Quite near the Isle of Thanet”.

For many years Alex Comfort was an Essex man himself, and St Andrew’s Hospital Billericay was where he had begun his clinical career. I suspect he would have found humour in that too.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout