Women aren’t being heard, but is medical misogyny the only thing at play?

The term medical misogyny is divisive and hits hard against men who care for women. But is there a deeper issue of mismanagement built into the system?

But is this “medical misogyny” – literally “medical hatred of women” – or medical mismanagement?

Accusations of medical misogyny inadvertently hit hard against men who are our friends, allies, colleagues, partners and sons who can be made to feel defensive and blamed; they also fuel hatred for those on the anti-feminist spectrum.

The term provokes polarised sentiments, whether expressed or not, making many men and some women feel very uncomfortable.

Perhaps this branding was selected by advocates to emphasise how generations of medical neglect have eroded the trust vulnerable women have in the health system.

Without lived experience, it’s impossible to understand how life shattering it is to exist year upon year in pain and be told in a patronising manner that “this is all in your head” and that the problem will go away with some cognitive behavioural therapy or an antidepressant.

There is nothing more invalidating than paying top dollar to seek help from a health professional, then leaving the room feeling dismissed, only to find years later that a crippling medical condition has been untreated.

A professionally qualified woman who attended my rooms for an opinion eight years into her medical journey told me she felt she’d lost the best years of her life to ill health for which she had already seen three gynaecologists, two colorectal surgeons, a gastroenterologist, a rheumatologist and a psychiatrist.

It turned out that endometriosis was responsible for all her symptoms and resulted in her having a total hysterectomy, removal of her ovaries and tubes (one procedure at a time), finally culminating in a partial colectomy (removal of a segment of bowel). This all occurred in stepwise progression and was interrupted by a series of post-surgical complications which delayed her recovery and return home.

Her relationship ended, she stopped working, socially isolated herself due to the crippling pain and recurrent diarrhoea caused by her endometriotic deposits, and suffered overwhelming feelings of guilt and inadequacy for how this was affecting her ability to parent.

The highly skilled doctors she saw made assumptions along the way that surgery and medication should have fixed her, their job was done, and that her ongoing symptoms must be related to other disease processes, hence the handballing to others and her eventual arrival in my rooms.

After threading the eight-year story together, my deduction was that there was failure of communication across the health sector resulting from each participant acting as if in a silo. Interestingly, she didn’t have a regular GP to help or advocate for her along the way and had lost track of the sequence of events. She felt utterly broken.

When at your most vulnerable, a basic expectation for anyone interacting with the health system is that the health professional listens, takes your concerns seriously and knows how to help you. A contract of trust, respect and confidentiality underpins this.

Some gaps in knowledge across the entry point into the health sector are to be expected, which is where specialisation comes into play, yet even this cannot account for the delays reaching a diagnosis and even misdiagnosis.

Gender bias has been pointed out as a contributing factor to medical mismanagement of women, and if we consider the evolution of the domains of science and medicine over the ages, they have been dominated by men who do not possess female body parts, do not menstruate nor give birth, so it is not unreasonable to suggest that some basic assumptions around women have been rooted in ignorance of women’s issues.

Women are not small men

A fundamental flaw in scientific thinking and drug trials to date was to assume that what works for men will work for women too, without considering the impact of hormones, sociocultural influences, our roles, muscle mass and anatomical differences. Unintentional errors by the health profession are based on a lack of knowledge, the assumption that common diseases present in women the same way as in men, lack of medical education through a gender lens, and lack of sex-disaggregated research.

Women, however, are not smaller versions of men, much like men are not like larger versions of women. This realisation has instigated several national inquiries into issues such as Menopause and Perimenopause (2024), The National Action Plan for Endometriosis (2018), Inquiry into Sexual, Maternity and Reproductive Healthcare (2023) to name a few, and the scientific world is now in a discovery phase around sex and gender-based differences affecting health.

Women comprise 51 per cent of the Australian population, they lose more healthy years of life from living with disease despite outliving men, so the problems that have remained unaddressed are a top priority.

Gender bias in medicine and the National Women’s Health Strategy (2020-2030)

Inevitably, issues around health inequity and equality invite us to consider what role women have played in designing the health system we have inherited, and the answer is very little until very recently.

The launch of the National Women’s Health Strategy (2020-2030) in 2018 set the framework for addressing these gaps in our health system affecting women across their life course and its five pillars were designed after extensive consultation with Australian women of all backgrounds. The pillars include maternal sexual and reproductive health, healthy ageing, chronic conditions and preventive health, mental health and the health impacts of violence against women and girls.

It’s a welcome response to the need for upgrading outdated systems, infrastructure and even the tenets of science which have been designed by men for everyone else.

The women interviewed in the focus groups for the National Women’s Health Strategy, and the subsequent national inquiries, commonly experienced such things as normalisation and dismissal of pain and heavy menstrual bleeding. They described unempathetic comments by doctors such as “some degree of pain during your period is to be expected”, “you’ll grow out of it when your system matures”, or “get pregnant and it’ll cure you”, despite the women describing this as severe enough to prevent them from attending school or work for days out of each cycle. Feeling dismissed, these women were then less likely to raise the same issues again, thereby delaying further investigation.

The inquiries revealed that systemic, mostly unconscious gendered biases are deeply entrenched in all society. Doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals, regardless of sex, are exposed to and become products of the same social and cultural influences as our patients, often practising what we have been taught, delivering our diagnoses, management and care, sometimes with an air of authority and often without question.

Having the advantage of health literacy and being bestowed with medical credentials creates the doctor-patient dyad of power and vulnerability, in that order. This also comes with great responsibility and accountability.

Minimising women’s pain

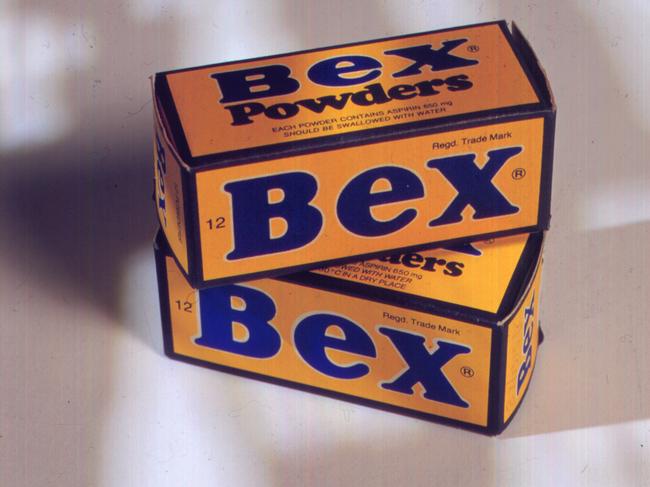

A nearly forgotten example of an ingrained tendency to assume women’s pain is in their head is demonstrated in the marketing of the product Bex, and its equivalents Vincents, APC and Veganin, also known as “mother’s little helper”. From the 1930s, women with any sort of pain, headaches or just feeling tired and stressed were recommended to have “a cup of tea, a Bex and a good lie down”, to help them get through their day. These products contained a highly addictive painkiller called phenacetin mixed with caffeine and aspirin.

Years later, phenacetin was associated with an increased incidence of renal failure in women, with up to 20 per cent requiring dialysis. There was also a huge surge in renal transplants and renal cancer directly related to its ingestion, and these products were taken off the market in Australia in 1977. It was a staple in most Australian homes, and nearly 50 years after the withdrawal of Bex and its cousins, we still know little about the women and their reasons for taking these medications, although the findings of the 2024 Inquiry into Women’s Pain give us some clues.

As a general practitioner who sees equal numbers of women and men, the inquiry’s findings are unsurprising:

• Up to 40 per cent of women have chronic pain and around 50 per cent of this is related to their periods and menstrual cycle.

• 30 per cent of those who have endometriosis, chronic pain, menopause and perimenopause experience mental health issues.

• About a third have a health condition that affects their ability to participate fully in work life.

• At least 20 per cent avoid social interaction due to the impact of pain.

The negative flow-on effects of having poor health for long periods on families, relationships and the economy cannot be minimised or ignored.

Health equity

More recently I’ve been hearing the argument that the injection of taxpayer funds towards addressing women’s health is disproportionately large when compared to the funding towards men’s health. This stance overlooks the significance of achieving equity in health which is demonstrated nicely in a pictorial that depicts a tall man, a shorter woman and a child each trying to look over a fence. The tall man can see over the fence easily, the woman needs a box to stand on and the child needs a step ladder with reinforcement to prevent the child from falling. Funding to address systemic gaps to achieve health equity is not dissimilar. Everyone benefits when women are healthy, pain free and can contribute to society to their full capacity. If we consider that the economic burden per year of women living with a single chronic disease such as endometriosis is estimated at around $7bn, the $87.2 million dedicated to address this disease as a once off contribution through the National Endometriosis Action Plan (2018) constitutes only 1.25 per cent of the recurring annual losses incurred. It’s a nominal but important investment towards a healthier society.

What is ‘women’s health’?

Health is not just the absence of disease, it is “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing”. Women’s health, by extension of this, is more than just dealing with problems to do with women’s different anatomy, their reproductive role and hormonal changes – it encompasses health in the context of the society we live in, their role in society and the interactions women have with these systems. Addressing each of these areas requires funding for sex-disaggregated research.

Such recent research revealed that heart disease, which is the major cause of death in women, can present differently compared with men, and not understanding this put women with heart disease at twice the risk of dying when presenting with a heart attack. Even medication which is usually prescribed for women and men in the same dose and strength needs to be re-evaluated as we have different muscle mass, metabolism and hormones.

Until very recently, studies on the effects of drugs have excluded women following the aftermath of the destructive effects of Thalidomide on unborn children. Partly as an act to protect women and their unborn children from similar disasters and partly due to the complexity of accounting for menstruation as a variable in research, all drug research has been conducted on men as subjects.

Other reasons for excluding women include the variability of the menstrual cycle – needing to account for this in research made the inclusion of women difficult.

However necessary these exclusions may have been at the time, they now need to change as the gaps in our knowledge are causing unforeseen secondary harms and discontent.

There are risks of inclusion also, and how far the pendulum swings towards the other side will be weighed against the potential risks this poses to women and their unborn children. We faced a very similar dilemma curing Covid-19 when vaccination during pregnancy for doctors and nurses created uncertainty. Yet healthcare workers were expected to trust the science in the face of a global pandemic.

What about men’s health?

There is no doubt that the spotlight on women’s health has highlighted other gaps in our health system and historically, sex-specific research and spending on women has helped men directly. Some breast cancer research uses sex-specific hormone receptor strategies to target breast cancer, similar to prostate cancer treatments. We’ve learned that breast and prostate cancer can coexist in families through the discovery of the BRCA1 (Breast Cancer gene 1) and BRCA2 (Breast Cancer gene 2) from back in the 1990s, and this now guides individuals on screening. The National Men’s Health Strategy (2020-2030) aims to address these gaps and is being implemented in parallel with the National Women’s Health Strategy.

Conclusion

The medical mismanagement of women has forced a review of our systems and invites researchers, policy makers and health professionals to apply a gender lens to their domains. It is an iterative process, and “living” practice guidelines are being developed to adjust to emerging science. Equity in health means no one should need to describe their patient experience as dismissive or demeaning, nor experience mismanagement – and the importance of health professionals actively asking themselves “how would it be to live in the other person’s shoes?” cannot be understated.

REFERENCES

• AIHW The health of Australia’s females (2023)

• Kincaid-Smith P. (1969). Analgesic nephropathy. A common form of renal disease in Australia. The Medical journal of Australia, 2 (23), 1131–1135.

• Armour M, Lawson K, Wood A, Smith CA, Abbott J. The cost of illness and economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in Australia: A national online survey. PLOS One. 2019 Oct 10;14 (10): e0223316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223316. PAID: 31600241; PMCID: PMC6786587.

• Endometriosis Progress Report

Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis AM is a leading women’s health expert and adviser, a senior honorary research fellow at the University of Melbourne department of general practice, and a longstanding member of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ expert committee on quality care.

This column is published for information purposes only. It is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be relied on as a substitute for independent professional advice about your personal health or a medical condition from your doctor or other qualified health professional.

It sounds like a simple enough request: doctors and other health providers should listen better and not dismiss what women are telling them.