Endometriosis: an ancient disease requiring new approaches

The first subsidised endometriosis treatment in 30 years could be life changing. As a GP, I know the grand chasm between men and women’s healthcare needs addressing.

Diagnosis can take anything from six to 12 years depending on who the affected person seeks help from, which equates to a failure of the health system because such delays are sometimes associated with medical mismanagement and dismissal of symptoms.

This can be attributed to a combination of factors which have created a grand chasm in medical and common knowledge around all things related to women’s health, earning itself the collective catch phrase of “medical misogyny”.

The list of barriers to early diagnosis and responsive health systems is long and includes poor investment in primary care and women’s health research, along with a societal reluctance to publicly discuss things to do with menstrual bleeding and “women’s bits”.

The intergenerational attitudes which have conditioned people and health care professionals to normalise period pain and heavy periods, favour the tendency to assume most women’s symptoms stem predominantly from a psychological basis.

There is global acknowledgment of the need to address this knowledge gap which encouraged the introduction of the National Endometriosis Plan (2018). Affected women who were surveyed in its development commonly reported, “they told me it was anxiety” or “my pain was dismissed” and were more likely to refrain from raising the same issues at subsequent visits. Along with endometriosis, women’s pain collectively has been neglected as the 2024 Pelvic Pain Survey in Victoria revealed, where as many as one in two women described living with chronic pain, for a variety of reasons. Had it not been for the annual national economic burden of endometriosis costing around $7.7bn as measured in absenteeism from work, loss of social and economic participation and use of the health system, tackling endometriosis as a chronic disease might have been parked in the too hard basket for another generation to address.

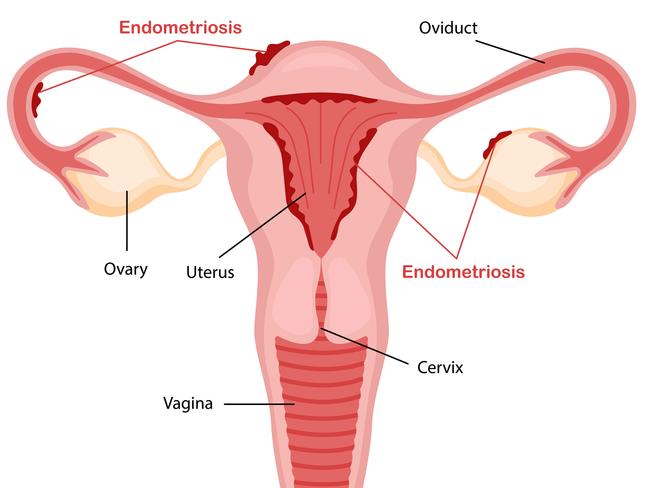

A cursory description of endometriosis is that this is an inflammatory disease of the endometrium; the endometrium is the lining of the uterus which is made up of a mix of cells and blood that forms the lush foundation for the implantation of a pregnancy, and which sheds as menstrual flow, when pregnancy is not achieved. For poorly understood reasons, the endometrium sometimes flushes back through the fallopian tubes instead of flowing out from the vagina, spreading endometrial cells and blood into the pelvic cavity and beyond, planting seeds of tissue on the bowel, bladder, ovaries, fallopian tubes and back of the pelvic wall, creating a sticky mess of scar tissue and clots, which react to the hormonal changes of each cycle.

There can be abdominal or back pain, heavy periods, diarrhoea, or knife-like pain on having a bowel motion, referred to as “dyschezia”, discomfort or bleeding with passing urine and pain during and after sex, which profoundly disrupts intimate relationships. Deposits which establish themselves on fallopian tubes and ovaries, are responsible for up to 30 per cent of all infertility.

Girls with mothers who have endometriosis are nearly 10 times more likely to develop this disease, so raising awareness can result in earlier intervention to reduce interruption to schooling, social participation and help future generations.

Endometriosis symptoms

Symptoms vary and there can be pain with and without periods, which can be confusing, not only for women but also for the health professionals who treat them. Women are often apologetic for coming in with a list of disparate symptoms for the general practitioner to detangle. Diagnosis requires persistence on the part of the doctor and persistence from the patient. Rarely is it a simple diagnosis to make; it requires several visits, investigative tests, trials of therapy with review, patience, trust and partnership.

Efforts to raise awareness include campaigns that talk about the three Ps, which stand for having “pain with your periods, pain when you pee and pain when you poo”. As a general practitioner, most women I’ve seen who have been diagnosed with endometriosis described feeling “bloated” or “tired” all the time. They rarely come in talking about their periods, because “pain” has been considered a woman’s lot in life and normalised since ancient times.

It takes several questions to segue into women’s menstrual cycles, which requires active listening without minimising the significance of the presenting complaints, including the common one I hear which is, “I feel bloated when I eat, do I have a gluten intolerance?” Interestingly, autoimmune disorders such as coeliac disease and thyroid disease commonly co-exist with inflammatory conditions such as endometriosis which means it takes time to drill down on how all this affects a woman’s participation in life, their work, intimate relationships, social activities, and mental health.

Attempts to simplify this process for health professionals and people with symptoms has prompted the development of online tools, such as the Raising Awareness Tool for Endometriosis (RATE) which has been developed by a multidisciplinary team of which I am a member, and the EndoZone symptom checker to name a couple. They can be accessed freely online and filled in before a visit to the doctor, which can streamline the conversation.

At the consultation with the doctor, next steps a GP will undertake after taking a thorough history, are making sure that cervical screening and other health checks are up to date. They will perform a physical and gynaecological examination, order blood tests to exclude anaemia, unplanned pregnancy, hormonal issues, and screen for pelvic and urinary tract infection. Often a referral for a pelvic ultrasound is issued and ideally, this should be performed at a specialist women’s ultrasound centre, which will leave a person around $150 to $250 out of pocket. Normal results simply exclude a host of other conditions but do not mean there is no endometriosis.

Therapy outlines the importance of pharmacological and non-pharmacological relief, lifestyle modification and the need for multidisciplinary care, much like other chronic diseases. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with a trial of an oral contraceptive are effective early interventions which reduce or resolve period pain and heavy bleeding, although if symptoms persist, a move to a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) in the form of a progesterone impregnated intrauterine device or an implant under the skin, are terrific.

Any trial of therapy in the early stages of the process, should be followed up with a review every three months with the GP to assess response to therapy, until a joint decision either to refer to a specialist gynaecologist or a specialist hospital outpatient department, is made. Where a referral to a gynaecologist is made, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might be ordered in cases where ultrasound is inconclusive as this gives more detail and can be fully rebated by Medicare, if used to plan surgery.

Is there a cure for Endometriosis?

As an inflammatory disease, endometriosis does not just go away. It needs to be controlled and managed over the life course and complicated cases may require surgical intervention through keyhole surgery (laparoscopy), to explore the pelvis and remove endometriotic deposits if found. It’s not uncommon to discover minimal or no endometriosis, suggesting other possible causes of pain such as pelvic congestion syndrome, adenomyosis (endometriosis in uterine muscle wall), uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts or torsion (where the ovary twists and turns on the ligament which attaches to the pelvic wall), scarring from infection such as a ruptured appendix or pelvic inflammatory disease or inflammatory bowel disease, to name a few.

However, frustratingly long wait times on public and private hospital lists, mean that affected women continue to be significantly disadvantaged financially, over a lifetime. This is the costly secondary effect of the gender health gap — which makes the listing of the oral hormonal treatment Visanne (generic name dienogest) on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme a monumentally positive step. Before listing this drug could cost up to $800 a year, which could be prohibitive, especially for young women. Taking it early can prevent disease progression, forgoing the need for laparoscopy and even fertility treatment down the track. It’s the first such listing for endometriosis treatment in 30 years to be subsidised and this might change the entrenched diagnostic and therapeutic pathways that require laparoscopy and can take up to 18 months on public hospital lists.

Until recently, establishing a definitive diagnosis required a laparoscopy which sits firmly within the purview of gynaecologists, not GPs, and has led the health profession down the surgical pathway, resulting in an oversight of the importance of the role of primary care in this process. Retraining the health sector across all disciplines is now under way with the development of learning modules, webinars and an upcoming World Congress on Endometriosis which is taking place in Australia in 2025, to address these gaps.

Most data around recurrence rates and response to treatment collected to date, are based on surgically diagnosed women and girls, not in primary care, which is the commonest entry point to the health system.

Current thinking is that treating symptoms early, becoming pain free, being able to participate actively in life as early as possible, is a more responsive model, regardless of the definitive diagnosis (unless of course, symptoms are due to potentially life-threatening disease such as cancer, infection, or pregnancy-related).

The national effort now being made to raise awareness, educate the health profession at all levels, conduct research, improve health systems and establish the national endometriosis and pelvic pain hubs, will hopefully reduce and even prevent the suffering women have endured.

A key point I repeat in all my consultations and public speaking events on this is that symptoms that are severe enough to stop a person from going to school or work, or that interfere with a person’s activities of daily life, fall outside the acceptable range and should be investigated further.

There is no doubt that one of the most satisfying aspects of being a GP is reviewing your patient months later to hear that their symptoms have improved or disappeared, and they are now living their life as they wish to.

Associate Professor Magdalena Simonis AM is a member of the National Endometriosis Expert Advisory Group, the Endometriosis Online Learning Research Steering Committee, RACGP Expert Committee for Quality Care and University of Melbourne Department of General Practice.

This column is published for information purposes only. It is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be relied on as a substitute for independent professional advice about your personal health or a medical condition from your doctor or other qualified health professional.

Resources:

• QENDO: Patient resources and free management app

• Pelvic Pain Foundation Australia clinician and patient resources

• EndoZone clinical and patient resources

• Endometriosis Australia patient advocacy group

• RATE (Raising Awareness Tool for Endometriosis)

References:

• The National Endometriosis Action Plan (2018)

• Inquiry into Women’s Pain Victoria (2024)

• Endometriosis and pelvic pain clinics

Endometriosis is a disease that despite being documented since ancient times, has remained a diagnostic challenge wreaking distress and in some, destruction on the lives of those affected. It affects at least one in nine women and girls over the course of their reproductive life, mostly spanning from menarche (when periods first start), to menopause (when women stop menstruating) and affects some nonbinary people too.