The next frontier to treat cancer: electricity

Scientists are testing electric fields and pulses against a range of diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and brain cancer.

Electricity is gaining newfound traction as a potential treatment for diseases, from rheumatoid arthritis to hard-to-treat cancers including glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer.

Pacemakers for decades have delivered electric pulses to keep heartbeats steady, and electroconvulsive therapy has helped people with serious mental illness after other treatments have failed. Now new technologies and devices are widening the scope of how electric fields and pulses could be used as medicine.

Biotech companies and researchers, including Novocure, SetPoint Medical and the University of Cincinnati, are deciphering how to shrink device sizes, deploy electric fields and hijack a person’s own immune response.

“We’re leveraging the electrical properties of cancer cells,” says Ashley Cordova, chief executive officer of oncology company Novocure, which developed technology that disrupts electrical forces at play in cell division to slow down tumour growth. “We think about bodies as being biological beings or as chemical beings, but we also are electrical beings.”

For mechanical engineer Tim Nugent, Novocure’s device offered a chance at more time with his family. The 62-year-old was diagnosed last fall with glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer, after he had trouble logging into his work computer and couldn’t answer basic questions. Nugent joined a clinical trial in February to give Novocure’s device a try after surgery, radiation and chemotherapy shrunk his tumour but failed to eliminate it completely.

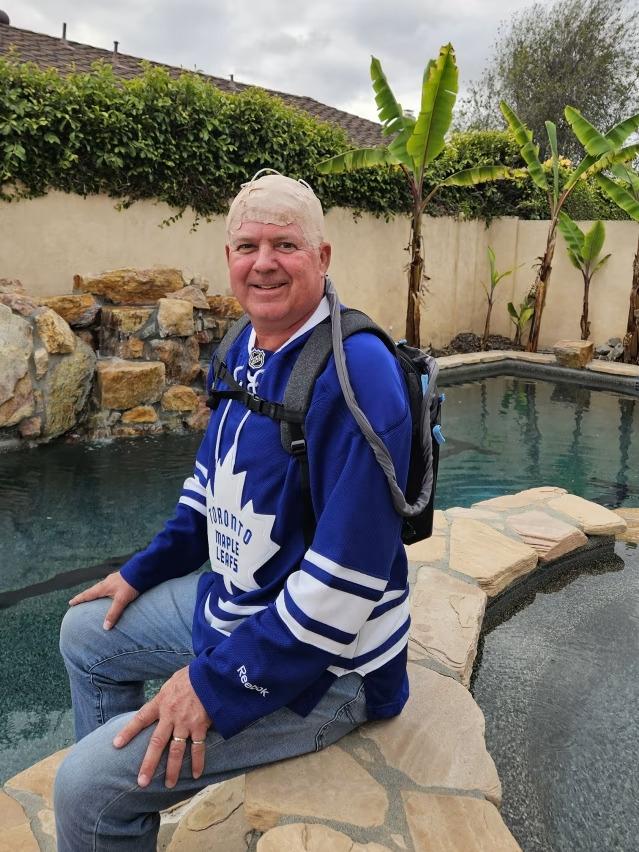

Tim Nugent wears Novocure’s device to treat his glioblastoma at least 18 hours a day.

Nugent wears adhesive patches containing electrodes on his shaved head, which deliver alternating electric fields at 200 kilohertz, equipped with a battery pack. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with glioblastoma and extends median survival by nearly five months when administered alongside standard chemotherapy.

“I’m going to be wearing it as much as I can,” says Nugent, who initially was sceptical of carrying around the 2.7-pound system. He now wears the device almost constantly, but that will likely change in the summer when he likes to water ski and scuba dive, he said. Patients are supposed to wear it for at least 18 hours a day, which can include when they are sleeping.

Cancer cells also have unusual electrical properties, enabling researchers to target them at specific frequencies and leave healthy ones unscathed, the company says. The most common side effect is irritation or a rash on the skin underneath the patches.

“I have to admit, I was very sceptical,” said Dr. Ola Rominiyi, a clinical lecturer of neurosurgery at the University of Sheffield in England, who is looking at how the fields could prevent cancer cells from repairing their own damaged DNA. “But it is a bigger improvement in average survival than we’ve seen for that group of patients for an extremely long period of time.”

A similar Novocure device is also used to treat mesothelioma, a cancer that forms in the thin tissue that lines internal organs, and was approved for some lung cancer patients late last year. Its trial in ovarian cancer didn’t help patients live longer, but there are promising data in pancreatic cancer and lung cancer that has spread to the brain. The company wants to expand into a range of cancer types.

“Electricity, if it treats cancer, it should treat most kinds of cancer,” said Dr. Kyle Wang, a radiation oncologist at the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center, who has helped conduct studies on Novocure’s device for glioblastoma. “The next 10 years are really going to be testing this.”

Wang is working on a trial testing whether glioblastoma patients will have better outcomes if they start to wear the device during their radiation treatment, instead of after. Others, including Nugent’s trial, are testing if the electric fields can help immunotherapies work better, since some data suggest that the cell death caused by the fields can jump-start a patient’s immune response.

Researchers are also developing tiny pacemakers for newborn babies who have heart defects, and seeing whether electrical stimulation to a person’s spinal cord can help treat depression. For Parkinson’s disease, the newest devices measure electrical activity in the brain and adjust their response accordingly, moving beyond the consistent pulses of earlier iterations used to treat the neurological disorder.

“All of these systems have become more nuanced and sophisticated in how they deliver that therapy,” said Dave Dinsmoor, a senior engineer at medical device company Medtronic, maker of the new adaptive Parkinson’s device approved earlier this year.

California-based SetPoint Medical is hoping to treat rheumatoid arthritis with an implantable device the size of a multivitamin that can send electric pulses down a person’s vagus nerve. The nerve carries electrical signals throughout the body and helps regulate digestion and heart rate. It also plays a role in the immune system, regulating the production of key proteins that cause inflammation.

Too much inflammation can lead to autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, and the company is hoping electric pulses can block the inflammation-causing process.

“We’re hijacking this system, and we’re going to make it do what it is supposed to do artificially,” said Dr. David Chernoff, chief medical officer at SetPoint Medical.

In SetPoint’s recent trial, some 240 patients with rheumatoid arthritis had the device implanted in their neck, and half got daily, minute-long electrical stimulation. After three months, some 35 per cent of stimulated patients had meaningful improvement in their tender or swollen joints and other symptoms, compared with 24 per cent of patients without it. After six months, half of the stimulated patients saw a benefit.

The device, which can feel like a tickle on the throat or sometimes a mild cough, activates early in the morning when most patients will be asleep. A hoarse voice and vocal cord dysfunction were the most common side effects, with less than 2 per cent of patients experiencing severe complications. SetPoint has submitted an FDA application for approval for rheumatoid arthritis and is testing the concept for Crohn’s disease and multiple sclerosis.

“You’ll see millions of patients treated with devices,” said Dr. Kevin J. Tracey, SetPoint’s co-founder and the CEO at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health. “Some patients will avoid having to take drugs altogether.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout