Life after the pill: Why it feels like no one understands your suffering

The belief, popularised on social media, that the pill is to blame for all our health woes is seeing women shun it in record numbers – but life on the other side can be a shock.

“And how long’s that been going on?”

The GP swivelled away from her computer screen to look at me, understandably suspicious of my request for a codeine prescription with as many repeats as possible.

“Oh, eight years? Maybe 10?” I responded vaguely, having lost track of how long I’d endured the debilitating migraines. Codeine was the only thing that put a dent in the pain, which had a habit of hanging around for days – every time I took the hormone-free placebo tablets in my contraceptive pill cycle.

But by that point, I rarely bothered with the so-called sugar pills, instead running several cycles of the active hormone pills together over several months. No period, no migraine.

“And you’ve been on the pill for how long?” the GP asked.

“ … Eight years, maybe 10.”

That GP – from a clinic I’d visited out of desperation after my supply of painkillers ran out – didn’t know me from a bar of soap, but she was convincing in her assertion I should stop taking the pill immediately. Like, that day.

There’s always a bit of wonkiness in the days and weeks after stopping the pill as your body readjusts to life without a daily hormone injection: brain fog, exhaustion, inexplicable crying, explicable crying.

Parts of it are surprising, too – amusing, even.

All I really wanted was for the headaches to stop – and they did. I haven’t had another one like it since.

What I wasn’t prepared for was the long tail of that adjustment – the ways in which it would impact my lifestyle and the way I see myself.

It started with a pimple. Not a pimple, a zit. A big, angry one, right on my chin.

Ten years on the pill meant a decade of impossibly clear, blemish-free skin – and that meant I was ill-prepared for the special horror of hormonal acne.

I was as patient about it as I could be, but the dermatologists I consulted prescribed strong retinoids and acids that triggered perioral dermatitis – basically, raw, peeling skin around my mouth, nose and eyes.

The oral medication prescribed to treat that made me overly sensitive to the sun, and the sunscreen I slathered on made me break out more.

The hair on my head fell out while it grew thicker elsewhere. I developed dandruff and yet my hair felt greasy a day after washing. My body odour changed. My weight fluctuated, as did my moods.

Who could possibly understand my suffering?!

Quite a lot of people, it turns out. Friends who’ve “come off the pill” in recent months and years regaled group chats for days about the ups and downs – mostly downs – of stopping daily hormone treatments.

One said she experienced premenstrual syndrome (PMS) for the first time in her early 30s after first being prescribed the pill as a teenager.

Another said her cycle contracted to less than 20 days, while someone else’s has shown up only sporadically in the three years since she stopped taking the pill.

One said she once relished being able to skip her period, but now laments her irregular menstruation as she tries to conceive.

Yet more said they were coming to terms with complex diagnoses that had been masked for years by the pill’s regulatory powers, such as polycystic ovary syndrome – a condition that causes small cysts on the ovaries and can disrupt ovulation, cause irregular periods and infertility – and pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder – a severe presentation of PMS that can cause temporary psychosis as well as headaches and joint pain.

There’s a mental wrangling to be done, too: several people told me about long stretches of insomnia and heightened anxiety.

The vast majority have spent thousands of dollars over months or years on consultations, medications, specialist appointments, psychologists, naturopathic therapies and treatments.

According to Dr Magdalena Simonis, an associate professor at the University of Melbourne’s department of general practice and a columnist for The Australian, this is all pretty much par for the course.

“The majority of women, within three to six months, are back to their normal cycle,” she says.

The contraceptive pill prevents ovulation – that is, an egg being released from the ovary – by altering levels of the body’s naturally occurring hormones, oestrogen and progesterone. At the same time, it makes it more difficult for sperm to reach the egg by thickening cervical mucus.

When the pill is no longer in the equation, ovulation returns to normal – whatever that is for the individual. Just don’t call it a “rebound”.

“It’s exposure to your normal hormone profile, and that hormonal profile may have evolved.

“So there’s no rebound – that’s a myth. It’s a misuse of the word, although it’s a popular one and it’s probably a sticky one, but it’s actually just a rediscovery of where you’re at,” Dr Simonis says.

Professor Danielle Mazza, head of Monash University’s department of general practice, says it’s important to take a holistic view of the post-pill experience.

“The pill is a very effective management tool … for the problems many teenage girls have … when their lives are relatively uncomplicated … But then if they come off the pill in their 30s, their lives are considerably more complicated,” she told The Australian.

“They may have developed other conditions along the way, whether those are mental health conditions that have manifested or other chronic diseases that may have arisen because that’s their genetic makeup.

“They may be encountering relationship problems – divorce, repartnering, domestic violence – financial issues, workplace problems, problems with existing children.

“So the way that you encounter and manage, and are able to deal with symptoms in your 30s and 40s may be very different, too … And so you have to think about the context.”

I began my work on this story fully prepared to be furious by the dearth of research into our collective post-pill reckoning. But the reason it’s nearly impossible for laypeople to unearth studies on this specific experience – and trust me, I tried – is actually much more, well, boring.

“When you come off the pill, you just go back into the broader population sample,” Professor Mazza says.

“So we have research on what happens when you don’t take the pills, (as well as) the prevalence of these conditions and how they manifest and, how women experience (them).”

And there’s the rub: the pill doesn’t cause those undesirable or difficult health outcomes – it just helps us manage them, even if we don’t know they’re there.

There isn’t a woman on the planet who’s sailed through life without experiencing acne or mood swings or hair growth in unexpected places or difficulty conceiving, and when you stop taking the pill – confronting though it might be – what you’re experiencing is your body functioning as intended in the life stage you’re at.

“The issue that many women encounter is that they’re used to feeling one way when they’re on the pill, and then when they don’t have the hormones on board … they get a bit of a shock,” Professor Mazza says, adding that a general lack of awareness about the many benefits of the pill beyond its contraceptive efficacy is also at play here.

It’s not to say those feelings of frustration and hopelessness aren’t valid – they are.

But this belief, popularised on social media, that the pill is to blame for all our health woes is seeing women – and young women, in particular – shun it in record numbers.

According to data from MSI – formerly Marie Stopes International – the number of monthly pill prescriptions issued in Australia has more than halved since 1992, down to 33,500 from about 80,000.

The reasons for that are many and varied: for me, it was the migraines; but other women report low, altered or volatile moods, affected libido and weight gain.

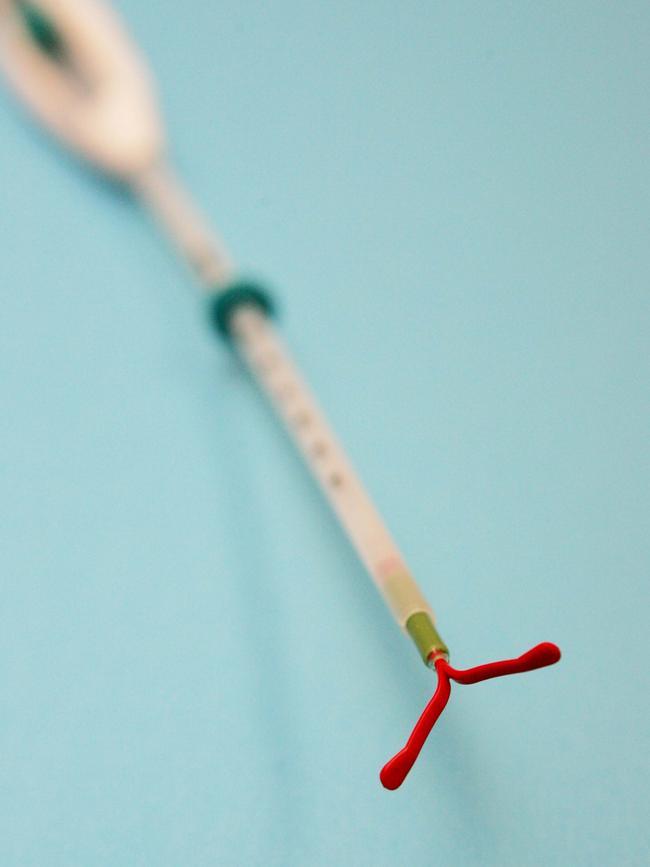

Plenty are ready to start a family, some have complex health considerations and treat the known risks with caution, while others prefer the relative freedom offered by more effective long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) – think hormonal implants such as Implanon or intra-uterine devices, or IUDs.

According to one study, uptake of LARCs in Australia is low compared with European nations, where that figure sits between 10 and 32 per cent.

Professor Mazza suspects the pill’s decline in popularity has a lot to do with the fact that young women are talking about it in a new, more connected way.

“Part of the problem that we’ve got in Australia – and internationally – at the moment is increasing distrust of hormonal contraception being driven by misinformation (circulated by) influencers on social media (and) undermining the trust that women have in medicines that have been rigorously trialled, tested, and where we’ve got a lot of experience in use,” Professor Mazza says.

She says that could be causing women to stop taking the pill without fully understanding what that means for them.

“Because not only are there the issues related to the fact that they are moving towards using less effective forms of contraception – which can result in unplanned pregnancies and all of the consequences that brings – but they are also perhaps not aware of the fact that, by going off (the pill) and going back to what’s called ‘natural cycles’, that they are exposing themselves to a whole lot of conditions that result from non-use of hormonal contraception.”

Make no mistake: the contraceptive pill is incredibly safe to use, and many of the hundreds of millions of women who’ve taken it worldwide never experience adverse effects.

It has a huge number of benefits, too, like reducing the long-term risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colon cancers, and providing an effective management tool for chronic conditions such as endometriosis, and it’s been revolutionary for women’s reproductive agency, independence and self-determination without altering fertility.

“The pill is just fabulous, isn’t it?” Dr Simonis says.

“It’s an effective contraceptive, really quite safe for the majority of women, controls the length and volume of the bleed, resolves the mid-cycle pain – which can be really severe in some (women).

“It also controls emotional fluctuation, so a lot of women who are on the pill in fact love it because there’s a mood regulation component, meaning that the PMS they experience normally disappears.”

It’s often pointed out that research into women’s health is severely lacking – but the contraceptive pill doesn’t fall into that category.

“The pill is one of the most researched medicines in the world,” Professor Mazza says.

“In order to get drugs registered, you need to do trials in different phases, looking at both efficacy and side-effects … and once a medication has been registered and utilised in a country, there is significant follow-up period to monitor for unforeseen (circumstances).”

Ask most women how they came to be on the contraceptive pill, and they’ll probably tell you it was the outcome of a relatively short conversation with a GP where the focus was on the importance of remembering to take the thing every day – not the potential long-term effects.

But Australian GPs and obstetric gynaecologists do adhere to rigorous guidelines developed in partnership with the UK’s Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health.

And Dr Simonis – who works full-time as a GP in addition to her research work at the University of Melbourne – says there are complex calculations and considerations at play when a GP prescribes the pill.

“We take those prescription guidelines very seriously … (because) a woman really needs to be qualified for the pill,” she says.

“There are several things, regardless of age, you need to find out.”

They include the presence of a clotting disorder, a family history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, past hepatobiliary diseases, cardiac conditions or heart murmurs and undiagnosed mental health conditions, as well as focal migraine or a history of hormone-sensitive cancers such as breast cancer or gynaecological malignant melanoma.

“There are other (contraindications) in older women, such as being a smoker over a certain age … because it increases the risk of stroke and ischemic heart disease, and that we take very seriously,” Dr Simonis says.

“And also uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension.”

Indeed, all the experts I spoke to for this story agreed: regular check-ins with a trusted health professional, be it a GP or a nurse practitioner, are essential.

“I think it’s really important for young women to establish a good relationship with a GP that they feel they can trust (to) give them time to talk through this stuff,” Professor Mazza says.

“And also to understand that … you often can’t solve these kinds of issues in one consultation.”

That means a regular discussion about your fertility plans and a general health check-up – after all, the more you know about your experience on the pill, the better placed you are to manage your experience after it.

“You can find something that works for you and continue to review it at different life stages, (because) what works for you when you’re in your 20s may not be the best option when you’re 30 or 40,” Professor Mazza says.

“GPs know the evidence, and they certainly know the evidence a lot more than the social influencer … so go to trusted sources like the family planning associations, government websites, and trained doctors and nurses who know their stuff and can give good advice.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout