How pediatricians created the peanut allergy epidemic

Peanut allergy is one of the most common among children in Australia and in the United States. A US expert explains how doctors may have inadvertently turned it into an epidemic.

“Hi, my name is Chase, and I’ll be your waiter. Does anyone at the table have a nut allergy?”

My two Johns Hopkins students from Africa, Asonganyi Aminkeng and Faith Magwenzi, looked at each other, perplexed. “What is it with the peanut allergies here?” Asonganyi asked me. “Ever since I landed at JFK from Cameroon, I noticed a food apartheid — food packages either read ‘Contains Tree Nuts’ or ‘Contains No Tree Nuts’.” He told me that even on his connecting flight to Baltimore, the flight attendant had made an announcement: “We have someone on the plane with a peanut allergy, so please try not to eat peanuts.” “What’s going on here?” Asonganyi asked. “We have no peanut allergies in Africa.” I looked at them and smiled. “In Egypt, where my family is from, we don’t have peanut allergies either,” I said. “Welcome to America.”

Declaring War on Peanuts

Deaths from peanut allergies are real, and living with the problem can be terrifying. Compounding the tragedy is knowing that America’s epidemic of peanut allergies is a largely avoidable consequence of our policy of peanut abstinence. The peanut allergy panic began in the 1990s, when the media started to cover stories of children who died of a peanut allergy, and doctors began writing more about the issue. In fact, peanut allergies at the time were rare and mostly mild: In 1999, researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital estimated the incidence of peanut allergies in children to be 0.6 per cent. But starting in the year 2000, the prevalence began to surge. Doctors began to notice that more children affected had severe allergies. What had changed wasn’t peanuts but the advice doctors gave to parents about them.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) wanted to respond to public concern by telling parents what they should do to protect their kids from peanut allergies. There was just one problem: Doctors didn’t actually know what precautions, if any, parents should take.

Rather than admit that, in the year 2000 the AAP issued a recommendation for children 0 to 3 years old and pregnant and lactating mothers to avoid all peanuts.

The AAP committee was following in the footsteps of the UK’s health department, which two years earlier had recommended total peanut abstinence. That recommendation was technically only for children at high risk of developing an allergy, but the AAP authors acknowledged that “the ability to determine which infants are high-risk is imperfect”. Using the strictest interpretation, a child could qualify as high-risk if any family member had any allergy or asthma.

Many well-meaning pediatricians and parents read the recommendation and thought, “Why take chances?” A generation of pediatricians adopted a simple mnemonic to teach all parents in their offices: “Remember 1-2-3. Age 1: start milk. Age 2: start eggs. Age 3: start peanut products.”

Despite these efforts, the problem got worse, and by 2004 it was clear that the rate of peanut allergies was soaring. Emergency department visits for peanut anaphylaxis — a life-threatening allergic swelling of the airways — skyrocketed.

In 2016, the Parkway School District in St. Louis County, Missouri, reported 957 students with documented life-threatening food allergies, most of which were to peanuts. The rate had increased 50 per cent from just six years prior, and more than 1000 per cent from a previous generation. In response, many schools enacted peanut bans. As things got worse, many public health leaders doubled down. If only every parent would comply with the pediatrics association guideline, they thought, we as a country could finally win the war against peanut allergies.

A Children’s Snack Leads to a Eureka Moment

Dr Gideon Lack, a pediatric allergist and immunologist in London, had a different view. In 2000 he was giving a lecture in Israel on allergies and asked the roughly 200 pediatricians in the audience, “How many of you are seeing kids with a peanut allergy?” Only two or three raised their hands. Back in London, nearly every pediatrician had raised their hand to the same question. Startled by the discrepancy, he had a eureka moment.

Many Israeli infants are fed a peanut-based food called Bamba. To Lack, this was no coincidence, and he quickly assembled researchers in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to launch a formal study. It found that Jewish children in Israel had one-tenth the rate of peanut allergies compared with Jewish children in the UK, suggesting that genetic predisposition was not responsible, as the medical establishment had assumed.

Lack and his Israeli colleagues titled their paper “Early Consumption of Peanuts in Infancy Is Associated with a Low Prevalence of Peanut Allergy.” However, the 2008 publication was not enough to uproot groupthink.

Avoiding peanuts had been the correct answer on medical school tests and board exams, which were written and administered by the American Board of Pediatrics. For nearly a decade after AAP’s peanut avoidance recommendation, neither the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) nor other institutions would fund a robust study to evaluate whether the policy was helping or hurting children.

Meanwhile, the more that health officials implored parents to follow the recommendation, the worse peanut allergies got. From 2005 to 2014, the number of children going to the emergency department because of peanut allergies tripled in the US.

By 2019, a report estimated that 1 in every 18 American children had a peanut allergy. Schools continued to ban peanuts, and regulators met to purge peanuts from childhood snacks as EpiPen sales soared. Pharmaceutical companies profited by raising prices: Mylan Pharmaceuticals’s EpiPen now costs $US600 ($912) in the US, compared to $US30 in some other countries. In a second clinical trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2015, Lack compared one group of infants who were exposed to peanut butter at 4-11 months of age to another group that had no peanut exposure. He found that early exposure resulted in an 86 per cent reduction in peanut allergies by the time the child reached age 5 compared with children who followed the AAP recommendation.

The Danger of Medical Dogmas

After these bombshell findings were published, I called one of my best friends from medical school, Dr. Drew White, now an allergist at the Scripps Clinic in San Diego, to ask him how they had been received. “It’s an impressive study,” he said. “After it came out, we immediately thought, ‘How are we going to fix this giant mess?’”

The AAP’s absolutism in 2000 had made the recommendation hard to walk back. Drew and I agreed: The AAP should have originally said something like, “We’re not sure.” At least that would have been honest.

Even today, the WIC program does not cover peanut butter for infants, a remnant of the AAP dogma. When modern medicine issues recommendations based on good scientific studies, it shines. Conversely, when doctors rule by opinion and edict, we have an embarrassing track record.

Unfortunately, medical dogma may be more prevalent today than in the past because intolerance for different opinions is on the rise, in medicine as throughout society. We can enact healthcare reform, close health disparities and give every American gold-plated health insurance, but if we continue to recklessly issue health recommendations based on an illusion of consensus instead of proper science, we’ll continue to struggle and waste billions.

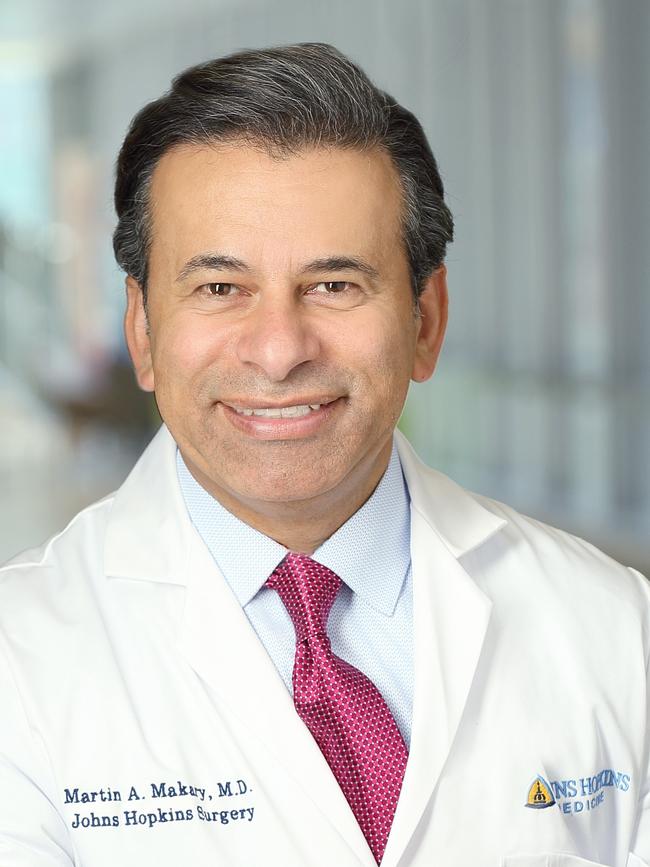

Dr Marty Makary is a surgeon and public health researcher at Johns Hopkins University. This essay is adapted from his new book, Blind Spots, When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Mean For Our Health, published by Bloomsbury.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout