Growing evidence suggests lower carbs and higher protein may be best for everyone

With the majority of Australians now classified as metabolically unhealthy, is it time to endorse low-carb eating for all?

The diet wars have been raging in Australia for decades. Experts are pitted against one another in acrimonious battles over what the evidence really says on low carb, meat, saturated fat, plant-based foods, and myriad other points of dietary contention.

But now, consensus has emerged on one thing: low-carb is an effective approach to maximise metabolic health. And with the majority of Australians metabolically unhealthy, is it an approach that everyone should follow?

In a highly significant move, the nation’s peak body for diabetes, Diabetes Australia, has entered a partnership with prominent low-carb diet proponent Dr Peter Brukner to promote his low-carb program to its members via Brukner’s organisation Defeat Diabetes. Brukner reversed his own diabetes and lost a substantial amount of weight through the approach.

Diabetes Australia is calling on 1.3 million Australians with type 2 diabetes to aim for remission using dietary interventions, which includes a low carbohydrate approach, high protein, healthy fats approach.

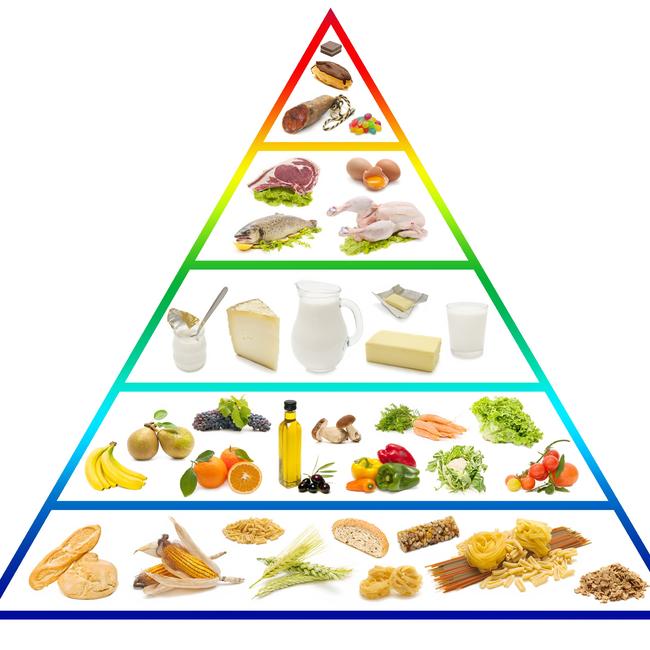

Dietitians Australia has also now endorsed low-carb eating after decades of adherence to the Australian dietary guidelines and the food pyramid, which state that wholefood carbohydrates should make up the majority of food intake.

Low-carb eating is now universally endorsed and scientifically proven to be of benefit for Type 2 diabetics or those with metabolic disorder, characterised by insulin resistance. Insulin is a hormone released by the pancreas that triggers the body to convert sugar into energy. When insulin develops, the body’s cells don’t react to insulin, resulting in excessive sugar in the blood. Over time, the pancreas keeps trying to regulate the blood sugar, producing more and more insulin until it wears out. As a result, blood sugar levels increase to the point where people may develop Type 2 diabetes.

It may seem self-explanatory that if a patient is essentially carbohydrate intolerant that reducing the intake of carbs would be a no-brainer. Restricting carbs keeps insulin low and forces the body to use fat for fuel. Such a dietary approach can reverse insulin resistance within weeks, allowing a substantial proportion of people to come off medication and return their metabolic markers to healthy levels. But it has taken the world’s major institutions many years to catch up with the science.

Diabetes Australia has had a position statement endorsing the low-carb approach since 2018, and is now widely rolling out the provision of a program for its members.

“The research does suggest now that dietary patterns that are lower in carbohydrate and higher in protein and fats is an effective approach to achieve sustained long-term weight loss,” says Professor Grant Brinkworth, Diabetes Australia’s Director of Research. “When you look at the evidence, a dietary pattern like a lower carbohydrate diet, compared to a traditional high carbohydrate, low fat diet is an effective approach for achieving or managing blood glucose control better, as well as reducing the risk factors for heart disease.

“There’s even emerging evidence suggesting that low-carb diets can be an effective strategy for achieving remission of type two diabetes. The Australian Government National Diabetes strategy has even actually also acknowledged the role of that we should look at in more intensive dietary approaches like lower carbohydrate diets for achieving improved by glucose management, as well as diabetes remission.”

Brukner says the widespread acknowledgment that a carb-heavy, low-fat diet, as still endorsed by most countries’ official dietary guidelines, including Australia, is destructive for those with metabolic syndrome, raises wider questions as rates of obesity and diabetes rise exponentially. “We’ve all grown up and being taught that the low fat approach was the only way to go diet wise,” he says. “Unfortunately, that’s still very much part of the medical profession, the dietetics profession and the general community. I think it’s fair to say that most doctors don’t understand diet very well, they tend to focus on medications and other means of management. And so many people seem wedded to the past.”

So should everyone eat low-carb?

The acknowledgment from the world’s major diabetes and dietary institutions that a low-carb, higher protein and higher fat approach can reverse metabolic disorder raises the questions as to whether it’s an approach that is worth considering for everyone.

Australia’s national dietary guidelines are currently under review. There has generally been resistance at the level of researchers and policymakers in charge of formulating the guidelines, a process that takes place behind closed doors, to consider that advice recommending that carbs make up the majority of ordinary people’s diet may be inappropriate in the modern age of chronic disease and obesity.

The dietary guidelines emphasise the intake of wholefood grains as the majority of calorie intake, with moderate protein and low fat for healthy Australians. But with two-thirds of people now overweight and obese, this approach is now arguably appropriate for only a minority of Australians, perhaps even a small minority. Some are arguing it’s time that the guidelines shifted to a low-carb preventive approach in the wake of a rising tide of population-wide metabolic disorder.

“I think that the latest number in the US was that around 93% had one aspect of metabolic syndrome,” Dr Brukner says. “So I suspect it’s probably not that much different in Australia. I’m hoping that the current iteration of the dietary guidelines would acknowledge that the fact that the previous guidelines have been for healthy people and recognise that maybe, for those with metabolic disorders, or even in order to prevent the development of metabolic disorders, we do need to modify the dietary guidelines.”

Professor Grant would also like to see consideration of an official population-wide endorsement for low-carb eating. “Lower carbohydrate diets are an effective approach for weight management and the management of bulk glucose control,” he says. “As a scientist, I’d like to think that all of our dietary guidelines are informed by the latest scientific evidence. And I’d like to think that the work that’s been done around lower carbohydrate diet would be considered as part of that review.”

As low-carb eating is taken up as a mainstream approach to reversing and preventing diabetes, doctors around the country are moving ahead of policymakers to learn more about how to address metabolic disorder in their patients through the approach.

Sydney GP Deepa Mahananda recently established with the Australasian Metabolic Health Society with a group of other GPs and has been rolling out workshops to keen doctors. She argues the measurement of serum blood insulin should be included as a standard test for metabolic syndrome along with the current standard measures which include blood sugar, waist circumference, blood pressure, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol.

“The definition around metabolic health is rapidly evolving,” Dr Mahananda says. “And as we learn more, we need to be really open to becoming evidence-informed.

“The low carb approach is really about looking at how we can modulate the hormone insulin. There’s an accumulating body of scientific literature underpinning metabolic health changes in our population.There’s quite a strong argument put forward that serum blood insulin should now be incorporated in the standard tests.

“And low-carb eating is arguably a good approach to prevention of changes in these metrics around metabolic syndrome.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout