Cattle gallstones, worth twice as much as gold, drive a global smuggling frenzy

A prized ingredient in China’s $60 billion traditional medicine industry, gallstones have become the must-have item among underground traders and slaughterhouse workers in Brazil and Australia who pilfer the stones while on the job.

In the dead of night at a slaughterhouse in Brazil’s southeastern farming belt, a group of men splattered in blood gathered around the entrails of a cow to see if they had hit gold.

“Just look at the size of that,” one worker said as he pressed the animal’s flesh through a sieve to reveal a hardened dark orange lump almost as big as a golf ball, glistening under the fluorescent light.

There it was: a gallstone.

One of the most prized ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine, cattle gallstones have become so valuable that traders are willing to pay as much as $5,800 an ounce — twice the price of gold — for the nuggets of hardened bile.

Herbalists use them to treat strokes as they grapple with a surge in hypertension, obesity and other conditions familiar in the affluent West. Such maladies are now widespread in China after a half-century of rapid development and the changing diets that have come with it. Surging demand for gallstones has sparked a global treasure hunt across the world’s top beef-producing regions, places as far apart as Texas and Australia, and especially here on the savannah of Brazil, the world’s largest cattle exporter.

“I thought it was a joke at first,” said Rafael Faria, a police investigator in Barretos, a farming town in São Paulo state that is the birthplace of Brazilian rodeo. He was recently called upon to probe a spate of gallstone heists and rampant smuggling as traders try to get them to buyers in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing.

Increasingly focused on hypertension and heart disease concentrated among China’s ageing population, Chinese traditional medicine is now a $60 billion-a-year industry, according to the World Health Organisation. China’s government and state media have encouraged its use as a source of national pride, especially during the recent Covid-19 pandemic, when Chinese scientists scrambled to develop vaccines and test more conventional treatments.

Beijing has also promoted traditional medicine overseas to complement its worldwide infrastructure push, building traditional health clinics in countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Spain and Mauritius to encourage locals to adopt it. Last month the government announced plans to train some 1,300 health workers to be sent out to countries involved in China’s globe-spanning Belt and Road port and transport initiative.

Conservationists blame traditional Chinese medicine for an alarming rise in wildlife trafficking. Governments have struggled to contain the trade in rare animal parts, from rhinoceros horns to pangolin scales and tigers’ penises. While the harvesting of cattle gallstones itself raises few concerns among conservationists, the substance is often packaged with parts from endangered species. For instance, a pill used to treat strokes is made from a combination of gallstones and rhino horns.

“The rapid growth of the TCM industry over the last few decades has exacerbated the pressure on endangered wildlife in Asia and beyond,” said the London-based Environmental Investigation Agency, which has followed the exploitation of wildlife by the industry over recent decades.

Dodging taxes, evading police

Selling gallstones isn’t illegal in Brazil, but trade in the little rust-colored rocks has largely flourished underground, with dealers dodging taxes and regulations, and armed gangs emerging to hunt down the treasure.

A few hours’ drive away from Barretos, in São João da Boa Vista, armed robbers recently broke into a farmhouse, tied up the owners and their 6-year-old grandson before making off with some $50,000 in gallstones.

Slaughterhouse workers in Brazil and Queensland, Australia’s top beef-producing state, have also been arrested in recent years for pilfering the stones while on the job, sometimes surreptitiously plopping them down their rubber boots.

In Uruguay, home to the highest number of cattle per capita in the world, a brother and his sister were sentenced to prison in September for trafficking over $3 million in bovine gallstones to Hong Kong without declaring them to the authorities, according to Interpol.

In most countries, people spend their lives trying to avoid gallstones.

Bilirubin, the dark orange compound produced during the natural breakdown of red blood cells, is normally excreted from the body. But when it builds up to form biliary calculi, or gallstones, the condition can be harmful and even fatal, for cattle, humans or any vertebrate.

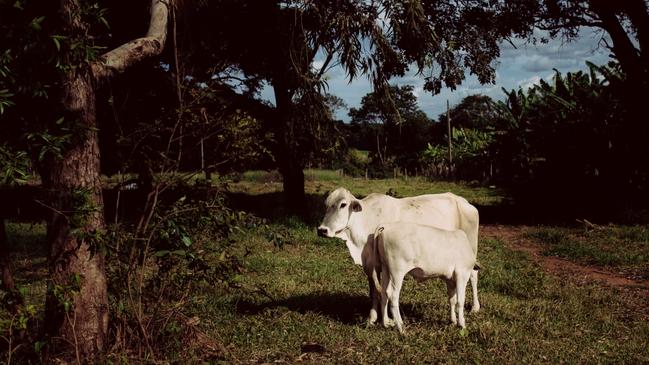

But here in Brazil, farmers’ eyes now light up as they swap stories about the size of gallstones they’ve seen, gazing at the lumpy underbellies of their cattle with new interest.

“If I knew one of them had a gallstone, I’d kill the lot of them myself,” said Pedro Benetti, a ranch hand, after unloading some three dozen cows from his truck to a nearby abattoir.

José de Oliveira, chief executive of Oxgall, a Brazilian gallstone trading company based in the center-west state of Goiás, said the quality — and price — of gallstones varies wildly, with chestnut brown rocks considered the purest.

“On average, we pay between $1,700 and $4,000 an ounce,” he said. That means a single gallstone can be worth more than all the meat on a cow.

The firm buys the stones from slaughterhouses and farmers, often transporting them by plane inside Brazil to avoid highway heists, before vacuum packing them and sending them to Asia, he said.

Many other producers operate illegally, shipping them hidden in everything from jars of jam to children’s toys to avoid burdensome regulations, according to police and exporters. In rare cases, fraudsters add finely ground-up bricks or inject sugar to the center of the stones to increase their weight.

With large swaths of the market still operating outside the law, data on the scale of the industry is sparse. But figures showing exports to Hong Kong, the most common stop-off point to China from Brazil, suggest a dramatic expansion of the market in recent years, according to a U.S. Agricultural Trade Office report issued last April.

Hong Kong’s imports of cattle gallstones have almost tripled in value to $218.4 million in 2023 from $75.5 million 2019, though researchers believe the actual size could be much larger. Brazil was the top supplier of stones to Hong Kong in 2023, accounting for some two thirds of all exports to that city, followed by Australia, Colombia, Argentina, the U.S. and Paraguay.

“In recent years, and particularly in 2024, the Agricultural Trade Office has received inquiries from local importers looking for U.S. ox gallstones — signalling an underlying demand for this by-product in Hong Kong,” the Trade Office wrote, encouraging U.S. producers to take a wider share of the market.

An age-old practice

Practiced for thousands of years, traditional medicine is still widely used in China, often in conjunction with Western medicine, and preparing the hardened bile for consumption is a fine art.

Once harvested, cattle gallstones are carefully cleaned and left to dry for weeks before being crushed down. In China, the powder is typically mixed with other ingredients from powdered buffalo horn to realgar, a reddish gemstone containing arsenic, and pressed into the so-called Angong pill.

“It costs about $200 for a couple of pills and it’s something that a family would keep at home in their pill box for an emergency,” said Dr. Donghai Wen, a China-born doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard University Medical School who trained in traditional Chinese medicine early in his career.

While many of the other purported benefits of cattle gallstones — from lowering fever to treating infection — have little grounding in science, recent experimental studies have found that Angong pills could help buy time in the treatment of strokes, said Dr. Wen.

A recent study on rats at Hong Kong University found evidence that Angong pills can delay the effects of an ischemic stroke, the most common type of stroke in which a clot cuts off blood flow to the brain.

Researchers found that several ingredients in the pill protected the membrane that surrounds the brain, potentially giving stroke victims an extra 30 minutes to get to hospital before suffering irreversible and, in some cases, fatal brain damage.

That has made the powder from cattle gallstones an ever-more-desirable item in China, where the WHO says strokes have become the leading cause of death.

Some 178 people per 100,000 die from strokes every year in China, more than three times the U.S. rate. Researchers blame rampant tobacco consumption in China, home to nearly one-third of the world’s smokers, as well as the country’s rapidly ageing population and factors linked to rising incomes, such as surging obesity in rural areas. An estimated 330 million people in China suffered from cardiovascular disease in 2023, up from some 230 million people in 2007, according to China’s National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases.

At the slaughterhouse

Here in Brazil’s farming belt, ingesting hardened cattle bile is generally looked upon with disgust.

“God, no!” said a worker at a slaughterhouse near Barretos when asked about the possibility.

He is responsible for slitting open the gallbladders in a high-security room at the back of the slaughterhouse, cordoned off by metal bars and under the watch of several security cameras. He said he typically finds at least one gallstone during the night shift, out of around 100 animals that are slaughtered.

While most of the cash from the stones goes to the slaughterhouse owners, he pockets a small commission from every rock he finds, he said, asking not to be identified for fear of being robbed.

“Sometimes it’s worth more than my monthly salary,” he said, adding that the smallest ones tend to be the purest and most valuable. “It’s very dangerous, once we get it out it goes straight in the safe.”

Daniela Gomes da Silva, a researcher at the São Paulo State University, said the hunt for gallstones across Brazil’s savanna has become so frantic that some producers have recently inquired about how to give their cattle gallstones.

“As if we knew!” she said. “We still don’t understand the exact mechanism that causes gallstones.”

While older animals and those put out to pasture tend to suffer with gallstones more frequently, it remains a mystery as to why some cattle develop them and others don’t, da Silva said.

One thing is clear: Gallstones are becoming rarer in Brazil, as the country becomes wealthier and its farms more efficient, da Silva said.

Affluent farmers can afford higher-quality feed and send their cattle to slaughter after as little as a year and a half, replacing them with new animals. All of this leads to more succulent meat and higher overall milk production, although typically fewer gallstones — a trend that could explain why the U.S. already exports relatively few stones, said da Silva.

Brazil’s farmers would be best to stick to what they know best — beef and milk, she said, cautioning producers against believing in tales spreading across the savanna of million-dollar gallstones the size of footballs.

“People hear about the high price tag,” she said, “and they’re starting to lose their minds.”

– Clarence Leong contributed to this article

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout