Business’s biggest hearts save lives of littlest hearts

The occurrence of often congenital heart disease in newborns is the same the world over – about one in every 100 births.

Days after the attacks on southern Israel by the depraved young fighters from Gaza last October, Hamas terrorists trained in hate and rocketry by Iran aimed their missiles haphazardly at central Israel. Some of these fell on the city of Holon, south of Tel Aviv.

They hoped for as much death and destruction as possible.

Ironically, those rockets detonated near the Wolfson Medical Centre, established by the Wolfson family – Poles who migrated to the toughest parts of Britain, Glasgow’s Gorbals district.

Isaac Wolfson made his fortune in mail-order shopping and established the Wolfson Foundation in 1955 to give away his fortune. It has given away almost $4bn and still does so at the rate of $61m annually.

And there is a firm Australian connection to the Wolfson Centre; based there is the Sylvan Adams Children’s Hospital. Doctors work and train there in pediatric coronary surgery in a project underwritten by the goodwill and funds arranged by Melbourne businessman Alex Waislitz, former vice-president of the Collingwood Football Club. Waislitz’s parents were also migrants from Poland.

Waislitz is the Australian patron of Save A Children’s Heart, an organisation that raises funds for the children’s hospital, which does not discriminate in the lives it saves: kids are taken there from Iraq, Morocco, Syria, Jordan and, until, October 7, more from Gaza than anywhere else. Even the children of senior Hamas officials were treated there.

But it is the young doctors trained there and who then return to their communities across the Middle East and northern Africa that make the biggest difference – those countries are where coronary heart problems remain poorly addressed in the very young who go on to develop life-threatening cardiac complications.

Recently, Dr Stella Mongella was in Australia to take part in a fundraising event arranged by Waislitz – in a room of a few hundred Australian businessmen and women the night gathered a further $700,000 for the cause – and she told the story of how she and her husband, also a pediatric cardiac surgeon, were saving children’s lives: two hearts a day, every day. Each.

Mongella spent two years in Israel gaining advanced training in the tricky surgery to repair little hearts in her home country. But her journey started well before that. Growing up in Dar es Salaam, her first language was Swahili; at secondary school she was taught in English. Her public service parents also spoke English. She met her husband, Godwin Sharau, at a hospital when she was a medical student and he was an intern.

Dealing with children’s hearts is more complex than adult hearts. Pediatric cardiology is the work of specialists – all of whom are fully qualified pediatricians. The occurrence of often congenital heart disease in newborns is the same the world over – about one in every 100 births. “But with more limited resources in Africa, it takes us longer to identify these children.”

There is no comprehensive system of foetal screening across Africa and the Middle East, and even today some tribes are semi-nomadic in rural Tanzania. These people have limited access to health professionals and their children’s heart defects can remain undiagnosed for years.

In Tanzania there is one pediatric heart centre. Mongella works there. Sharau is its lead surgeon. By the time children arrive, they have been sick their whole lives. The World Health Organisation recommends one such centre for every five million people. This subjects doctors to the testing challenge of adjudicating which children are most ill and most in need of treatment – “to pick and choose”, as Mongella puts it.

Meanwhile, piling on pressure is the trend for acquired heart disease in poorer countries. Rheumatic heart disease can stem from untreated throat infection. It is disproportionately common among Indigenous Australians. In Tanzania there may be 300,000 children with the condition. Australia is home to about 10,500 cases.

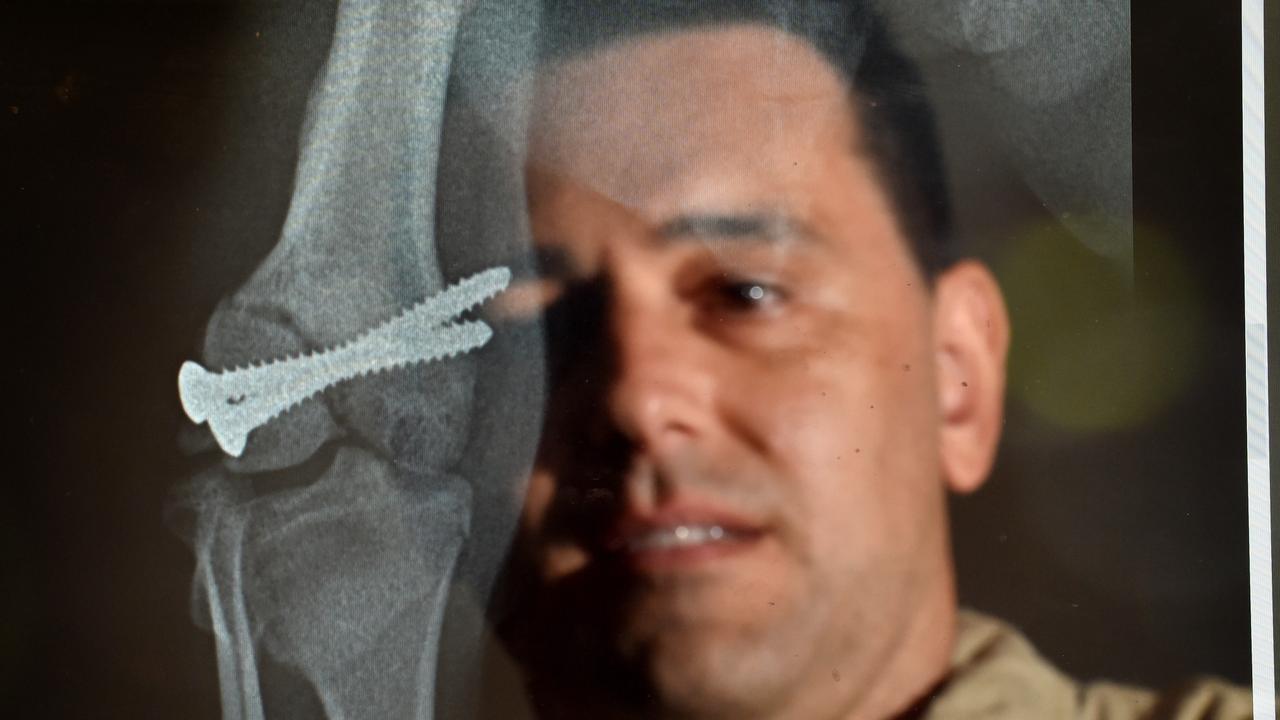

The so-called “hole-in-the-heart” is most common. This might be where the walls of the heart chambers are defective. Mongella makes the treatment sound simple enough: “We close them up.”

The symptoms are a giveaway for trained medical professionals: fast breathing, persistent cough and susceptibility to infections. Commonly, such children don’t gain adequate weight and miss other developmental milestones, like the age at which they can sit, crawl and walk.

Mongella can repair two hearts a day. Every two months the team tries to blitz through five cases a day. That still leaves a waiting list many lifetimes long.

It is routine for her these days, but Mongella remembers clearly the first time she operated to save a child: “It is a very daunting task. But we have no choice but to take it on. When you are working in the country’s only heart centre you have to push through any crisis of confidence you may have.”

She was taken on for further training by Save A Child’s Heart, part of its second generation of pediatric surgeons. Not only does SACH offer and pay for training, it spends its funds to supply the expensive equipment needed for the work done by the likes of Mongella.

The organisation also hosts children in Israel for tricky surgery, paying their fares and accommodation, while providing treatment free along with ongoing medication. “All they (unwell children) have to do is bring their passports,” says Mongella. SACH has saved more than 7500 young lives across 65 countries so far.

She has three children, two of whom want to become doctors. They’ll lead busy lives.

About 15 years ago, Waislitz began to concentrate more on philanthropy and he asked friends which were the most effective health projects – impactful, scalable and with international reach – in which he might become involved. “They came up with Save a Child’s Heart, so I visited them, and my involvement with them has been all the way since.” He said he was hugely impressed with the staff and what they were trying to achieve – and also attracted to the idea that it was not political, nor religious; just a focus on saving children, no matter who they were nor where they came from.

To deal with the backlog of young patients, and the increasing demand, Waislitz decided to focus on training doctors and other members of the cardiac units. For this he designed and supports a scholarship system.

“I thought it best to train these doctors and the teams in the cardiac units in Israel at the centre of excellence,” he said. They would return to their home countries, form cardiac units and continue to save lives while training others – partly funded by SACH, which sends regular missions of support.

“I thought that would be the most impactful approach. And now it is starting to happen. There is a centre in Dar es Salaam, a centre in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, last year we opened in Kigali in Rwanda and this year we’ll open in Zambia.”

Waislitz spoke to Sabin Nsanzimana, Rwanda’s Health Minister, himself a Swiss – trained specialist in epidemiology, who has ambitions for his country to use the SACH program to become the regional centre for saving the lives of children with heart defects.

(To make a tax-deductible donation to SACH go to saveachildsheart.org)