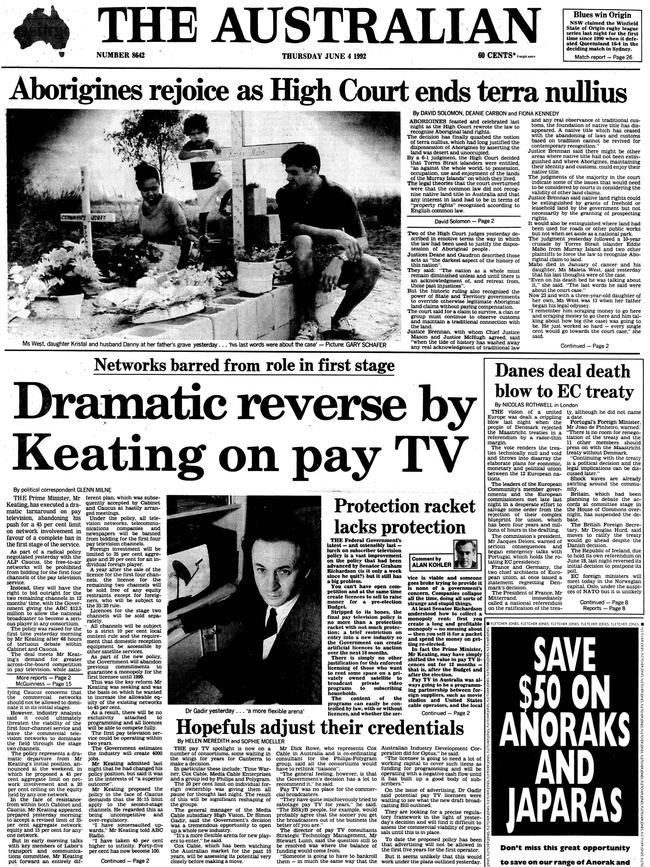

Writing after the Wik judgment, the 31-year-old Indigenous leader Noel Pearson called for a reconsideration of Australia’s history that acknowledged the suffering of the first Australians while repudiating the pangs of national guilt.

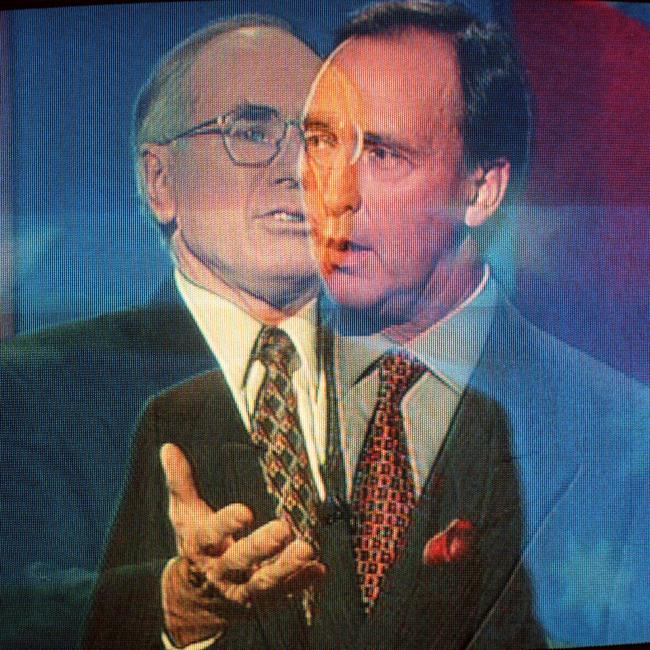

Three years after Paul Keating’s historic election victory in 1993, Labor’s grip on power was weakening. According to The Australian’s former editor-in-chief Frank Devine, the 1996 election battle between John Howard and Keating projected a presidential-style race, featuring a “symmetrical” and reliable Howard and a snazzy and “polished” Keating.

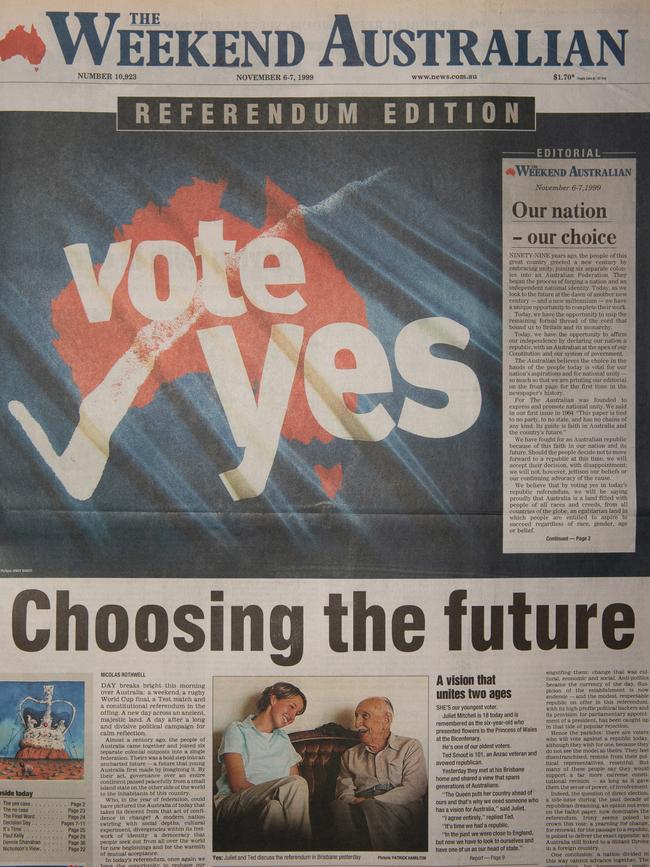

After his election win, Howard went on to claim a second victory against his old Labor rival, with the defeat of the 1999 republic referendum. The Australian was a staunch supporter and advocate of a republic.

“We believe today’s referendum is, and should be a choice between attachment to an anachronism and confidence in our future,” The Australian declared on referendum day.

The Australian’s editorial was run off the front page, a rare occurrence and a sign of the masthead’s commitment to the republican cause in this country.

OUR NATION, OUR CHOICE

- Editorial first published November 6, 1999

Ninety-nine years ago, the people of this great country greeted a new century by embracing unity, joining six separate colonies into an Australian Federation. They began the process of forging a nation and an independent national identity. Today, as we look to the future at the dawn of another new century – and a new millennium – we have a unique opportunity to complete their work.

Today, we have the opportunity to snip the remaining formal thread of the cord that bound us to Britain and its monarchy. Today, we have the opportunity to affirm our independence by declaring our nation a republic, with an Australian at the apex of our Constitution and our system of government. The Australian believes the choice in the hands of the people today is vital for our nation’s aspirations and for national unity – so much so that we are printing our editorial on the front page for the first time in the newspaper’s history. For The Australian was founded to express and promote national unity. We said in our first issue in 1964: “This paper is tied to no party, to no state, and has no chains of any kind. Its guide is faith in Australia and the country’s future.’’

We have fought for an Australian republic because of this faith in our nation and its future. Should the people decide not to move forward to a republic at this time, we will accept their decision, with disappointment; we will not, however, jettison our beliefs or our continuing advocacy of the cause. We believe that by voting Yes in today’s republic referendum, we will be saying proudly that Australia is a land filled with people of all races and creeds, from all countries of the globe, an egalitarian land in which people are entitled to aspire to succeed regardless of race, gender, age or belief.

The referendum model, approved by last year’s Constitutional Convention, envisages a president appointed by a two-thirds majority of federal parliament, after nomination by the prime minister and opposition leader. This would ensure a non-political appointment and would preserve our tried-and-tested system of government. A No vote today would cast the republic debate into limbo, and monarchists like Mr Howard would make sure it stayed there.

We believe today’s referendum is, and should be, a choice between the monarchy and the republic. Between attachment to an anachronism and confidence in our future. Between an emblem of aristocracy and an emblem of our egalitarian ethos. Between another country’s symbolic leader, with mere residual relevance to Australia, and our own head of state, able to represent us at home and abroad.

This is a stark choice. We can make it today by voting Yes.

PORTRAIT OF TWO LEADERS

This is an amazing election campaign. Most since Gough Whitlam scored in 1972 have been labelled “presidential” but this one goes beyond virtual reality.

There are so many echoes of a US presidential election that some mornings you wonder if you will be seeing the Opera House or the Statue of Liberty during the day.

Is this the way people want it to be? There is no reason to think otherwise. When the election comes up in conversation, practically nobody talks about anything except Keating versus Howard. Yet this election, like all that have preceded it, is still a contest for seats in parliament, at the end of which the successful candidates will choose one of their number as leader of the party.

The leader of the majority party will become, informally, since there is no explicit constitutional provision for a prime minister, first minister of the Crown. Quite a subsidiary role, if you take it literarily. That is not, however, the way the voters, the media or the two leading candidates are taking it.

The 1996 election campaign will have a profound effect on government in Australia, whoever wins. Claims are being made for the office of prime minister which neither precedent nor Constitution sustain. The nature of the republic, if there is to be one, is likely to be changed by the 1996 campaign in ways that nobody has seriously canvassed.

The media, even parts of it that also doggedly cover the issues, is delighted with the old-fashioned melodrama and simple plot-line of Howard versus Keating. Never, in my recollection, has there been so much straining in print to depict the character and personality of the principal contenders for the White House, I mean Lodge.

The liveliest use of analogy so far has been, for Howard, “an effervescent, optimistic Willie wagtail”, and for Keating, “a black snake, sly, slippery and dangerous”. My choices may suggest a bias towards Keating. A snake is a more formidable creature than a Willie wagtail. Other character sketches of Howard in the first 10 days of the campaign have included: Churchillian, a big Normal, a gray, suburban functionary, a wily old campaigner oblivious to insult and impervious to pain, colourless, cautious but doggedly determined, seasoned and crafty, the best knife-sharpener in the business and one who wouldn’t recognise the future if it hit him in the groin.

Keating has been perceived as: a hustler, passionate, headstrong and divisive, abrasive, aggressive and argumentative, notoriously intemperate of language, an Aussie street fighter, savage and uncompromising, an eagle ready to pounce and somebody who couldn’t run a pig farm.

The most US-style presidential campaign ad so far is the daring one featuring people saying you may not like Keating, but you have to respect him. However, an American campaign manager would have had conniptions about the blonde woman with the threatening glasses who sneers: “It can’t be Johnnie Howard. Imagine him.” She has her own problem. Nobody likes her. Howard would be the easier candidate to sell if he were running in a genuine presidential campaign.

There is a reassuring symmetry to his life. Lower middle-class clever kid who got into an elite state selective school, Canterbury Boys High. Onward and upward through the University of Sydney law school. Heading for big-firm affluence and status as a Sydney solicitor. Marriage. Kids. Politics. One nice suburban residence in an unflashy neighbourhood. Reads a bit. Amiable one-pot screamer. Loves cricket. A sort of Forrest Gump with brains.

Keating’s profile would keep image polishers on edge for the duration of the campaign. Too many paradoxes.

Somewhat affluent working class. Little education to speak of, yet expansive claims to cultural and literary expertise and enthusiasms. No profession and negligible work experience except politics. Married. Kids. Reputation for charm and warmth in private, but snarling yobbo in public. Expensively groomed, keeps company of newly rich and has taste for grand houses in fashionable neighbourhoods. You think about Jay Gatsby.

But are voters happy to give presidential executive authority to someone who, now that the role of the Crown has been challenged, has no restrictions on his actions so long as he holds the numbers?

That is what they are being asked to do. I think the 1996 election campaign will put paid to the idea of a minimalist republic and not only of an appointed ceremonial presidency but also of an elected ceremonial presidency.

As well as developing during the 1996 election – and probably the one that follows it – a taste for the razzamatazz of presidential politics, people will come to see the impossibility of having prime ministers with only fictive brakes on their “leadership”. They are likely to prefer an executive president, with a cabinet and command of the bureaucracy, watched over by an independent legislature supported by the staffs of committees and MPs. Neither man may realise it, nor even want it, but that is what Keating and Howard are campaigning towards.

The Dead-end of guilt politics

Indigenous leader Noel Pearson writes responsibility for the past and the future – rather than guilt – should define Australia’s relationship with its history.

- By Noel Pearson. First published November 22, 1996

It is very clear that guilt about Australia’s colonial history is what the Americans would call a “hot-button issue” in the Australian community. The polls will tell you this: Most ordinary Australians are offended by any suggestion that they should feel guilty about any aspects of the country’s past.

They vehemently reject any responsibility for it. Many will reject any notion that some of the legacies of the past live in the present and need to be dealt with.

In his Sir Robert Menzies Lecture this week, Prime Minister John Howard supported this view. He characterises the recent historiography of colonial relations and the discussion of Australian history during the Labor ascendancy as having been altogether too pessimistic. Following Geoffrey Blainey’s description of the “black armband view of history”, Howard implies that a history has been cultivated by the politically correct classes which urges guilt and shame upon Australians about the national past.

There is no doubt in my mind that the Prime Minister’s characterisation of the historiography that has developed over the past 25 years, and the particularly lively discourse in the wake of the High Court’s decision in the Mabo case, which judgment canvassed the legal and moral implications of this history, is a characterisation that resonates with the instincts and feelings of ordinary Australians.

It is now well understood that up until the 1960s there was, in the writing and teaching of Australian history, the historiographical equivalent of terra nullius: a history that denied or ignored the true facts of the colonial frontier. This was what the late Professor Bill Stanner called the Great Australian Silence.

The popular Anglo-Celtic story of Australia’s past was seriously distorted by significant omissions and by some straight-out fictions, such as the fiction of “peaceful settlement”. However, there is now accumulated a new Australian history, to which Professor Blainey has also contributed, which tells the story of the other side of the frontier. The debate today is not so much about the facts of the past. There is generally common ground about them. The debate is about how Australians should respond to the past.

There is every indication that Australia is mature enough to deal with these questions: How do we explain the past to our children? How do we, as indigenous people, respond to the legacy of colonialism and that brutal, troubled, culture by which we were dispossessed? Do we reject it outright and, furthermore, do we require Anglo-Celtic Australians to spurn their origins in the name of penance and of solidarity with us?

Such a response to our history is quite inappropriate. It is at odds with the quest to discover “what unites us” as well as “what separates us”. We need to appreciate the complexity of the past and not reduce history to a shallow field of point-scoring. I believe there is much that is worth preserving in the cultural heritage of our dispossessors.

My feeling is that guilt need not be an ingredient in our national (re) consideration of our history. For those Australians who are not still afflicted with the obscurantist tendencies of the past, guilt is not a feature apparent in their psychology.

TUNING INTO THE THREDBO DISASTER

Not since yachtsman Tony Bullimore’s rhythmic tapping on the hull of his upturned boat has a nation strained so hard with ear cocked for the sound of human survival.

Australians gathered around televisions and radios all weekend to catch the latest episode in a real-life drama with heroes, victims, a race against time and the ever-present danger of another slide at Thredbo, which engaged us vicariously from the safety and comfort of living rooms throughout the country.

Channel Nine anchor Jim Waley told viewers yesterday they would be familiar with his next guest, a rescue worker who four days into the Thredbo landslip is now almost a household name for those loyal to this network’s coverage of events.

These tragedies are made for media and increasingly Australian television is following the US example of setting up electronic base camps wherever disaster strikes –for news flashes, live crosses, and entire programs broadcast on the scene or as near as, damn it.

Whether it’s an act of national terrorism like Port Arthur or Oklahoma or a small-scale domestic drama like a little girl caught down a hole, we become transfixed by what unfolds.

Perhaps that is why the marathon endurance test of events like Thredbo produce such a visceral response within the larger community cut off from direct involvement in the human chain of emergency workers but feeding on developments through an umbilical electronic cable.

The more we follow what’s happening, the more intimately we become associated with the smaller community actually participating in the crisis. However remote we may be from the Thredbo accident, there are archetypal lessons in its randomness and the role of hope and optimism in hanging on until help arrives.

READER’S VIEW

Petty republic

It is embarrassing to hear the pathetic TV ads for a republic, “To show the world we are an independent nation!” For goodness sake. Where the heck have these people been living all their lives? How can they imagine that we are not an independent nation? If we must be a republic, will someone please let us have a good reason apart from a petty jealousy that one of us can’t be king or queen and the symbolic head of a group of friendly independent nations. From my 10 years of living overseas, I found our system is not only greatly admired but even envied in the rest of the world.

FRED STEPHENS, MOSMAN, NSW OCTOBER 25, 1999

Red-bloods

We live in complex times. My parents were Italians. That makes me a multiculturalist, a particularly recalcitrant one as I hadn’t been separated from them early enough to be weaned from espresso coffee and food cooked in olive oil, including fish and chip. John Howard tells me that it’s OK andI can stay if I speak English. But Pauline Hanson’s new Decalogue warns me that if I persist, I’m not a red-blooded Australian and I can just go back to where I came from in the first place. My blood has checked out red, so I won’t have to go back to Little River, where I was born. To add more complication, the pollsters have found that 73 per cent of people agree with Hanson. In my 60 years I’m still virgin to the poll takers and I have concluded that the opportunity of meeting someone who has been polled is not greater than the chance of meeting a Venusian. Their own grandparents, their great-aunts, Billy Hughes, Robert Clive of India? Where do they poll them? Outer Woop Woop, Kabul?) The Prime Minister, for reasons known only to himself, has let the smelly genie of racial intolerance waft across Australia. I look forward to his next necessary feat, getting this sad, discord-making essence back and re-corked inside the bottle of bipartisan convention that had stood us well these last 50 years.

R.A. BAGGIO, WERRIBEE, VIC OCTOBER 16, 1996

Bill’s big blunder

Bill Clinton, for all his wanderings, has been a good President. I hope this recent and sudden US attack on “terrorist installations” is not intended in any way to distract the American public from the American pubic. SARA HOUREZ, MALABAR, NSW AUGUST 22, 1998

Non-gender terms

Political correctness has become truly ridiculous. One expression that enraged me most was a remark made by an ABC announcer when discussing the recent cricket Tests between Australia and Sri Lanka, in describing our players as “batspeople”! It made them sound entirely crazy.

PETER HEERY, HUNTERS HILL, NSW. MAY 2, 1996

As the long era of economic reform closed, the 1990s opened with momentous change in Australian race relations, starting with the Mabo decision and Redfern address and ending with the Wik judgment and the Bringing Them Home report.