Massacres and Mabo: Much to gain in recognition of horrible history

In the ‘90s our nation disposed of terra nullius, reckoned with a massacre and moved from Hawke to Howard. Look at how we covered the biggest events of the decade.

The Australian is turning 60 and we invite you to celebrate with us. Every day for the coming weeks we will bring you a selection of The Australian’s journalism of the past 60 years, from news stories to features, pictures, commentary and cartoons. See the full series here.

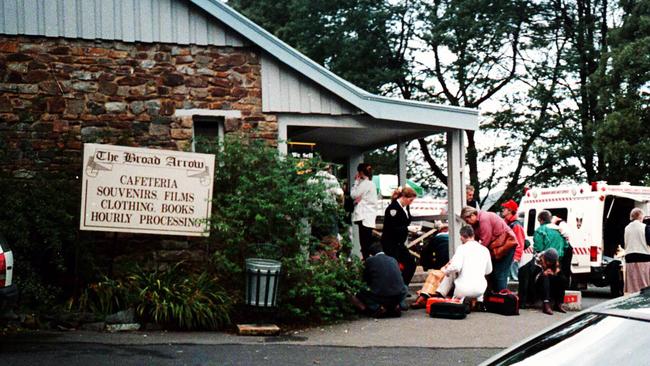

Just days after the massacre of 35 people at Port Arthur, The Australian carried reports on the ripples of emotion spreading from the horror. A debate on guns was soon to follow.

BLOODY SUNDAY LIVES ON IN LOVE, GRIEF AND HATE

- By Cameron Forbes. First published on May 1, 1996

Two bouquets of flowers, one wrapped in yellow, the other in pink, lie on the concrete steps of the Broad Arrow cafe in Port Arthur, left in love.

Inside 20 people were gunned down last Sunday.

On the wall of the Royal Hobart Hospital is sprayed “An eye for an eye!”, scrawled in hate. Inside, recovering from burns, is 28-year-old Martin Bryant, the man accused, so far, of one of the 35 murders committed in and around the tourist attraction.

The graffiti is a sign that Tasmania’s numbness is turning to an anger that will burn fiercely through a small island population of 460,000 which is in many ways inward-turned.

Yesterday there was a poster on the roadside outside a store near Port Arthur. It had the Hobart Mercury masthead, the single, stark word Massacre.

Around noon yesterday, a car drove past it, carrying a group of women and the bouquets. It wound up hills and then down close to the waterfront and the burnt-out destruction that was the Seascape cottage. Police were carefully sifting the ashes, and an hour later they would find the unrecognisable remains of the final victim. Three people died in there. Martin Bryant emerged alive.

At the historic site, bathed again in pale golden sunlight, they spoke to the young constable guarding the pathway, keeping watch for the media or the curious/ghoulish. The last of the 20 bodies had been moved from inside the Broad Arrow on Tuesday night but inside, working under arc lights, gloved forensic scientists were still piecing together the start of the terror.

The constable spoke to his superior and the sad procession walked down the hill, carrying the bouquets. The police quickly set up a makeshift shrine on the steps, marked off by their blue and white tape. “The women were in tears. The coppers were in tears,” Inspector Graham Hickey says. And he is near tears himself as he speaks of it.

He had been inside the cafe, something he’d never forget, he says. “I suppose I’d be much happier if I’d never gone in and had a look at it.” Now, he says, there are the other victims, the next-of-kin. He looks towards the bouquets. “It’s very hard to handle, I always find, and we understand there’ll be a lot more people coming in before the day’s out.”

Picture a mound of 20 bouquets and four more for those who died just outside the cafe.

Police were moving away the last of the abandoned belongings from the cafe, signs of what was to be a happy outing, most of them: a cask of red wine and a cask of white wine and a couple of six-packs of beer.

The cafe, Inspector Hickey says, will be locked once the police have finished their work. He predicts it will never open again. Perhaps it will be left as a memorial.

Perhaps it will be bulldozed in an attempt to exorcise the tragedy.

The site and a deal of the surrounding community of 2000 have lived off tourism, a tourism built on cruelty and suffering. But this cruelty and suffering is seen from the comfort of a century’s distance.

Port Arthur has also nurtured its own myths. “Since the 1870s,” a poster proclaims, “unusual occurrences and sightings of apparitions have been documented at Port Arthur.” Tourists are encouraged to “stay overnight and discover for yourself the systematic floggings, solitary confinement and psychological torture that made Port Arthur the fearful place it was”. Was?

Is. Of those who died, 12 came from the close-knit community that lived near the ruins. Yesterday afternoon, friends and relatives made a pilgrimage to the new shrine at the cafe.

Because of Bloody Sunday, Port Arthur has its fearful present.

DISPOSING OF TERRA NULLIUS

- Analysis by Padraic P McGuinness. First published June 5, 1992

The High Court of Australia in its judgment on the Mabo case, announced this week, has taken a significant step forward in asserting its role as a legislative as well as judicial arm of the Commonwealth. It has changed the law on the status of Aboriginal land claims.

It has also significantly altered the status of Aborigines in Australian society. It has done this by a mixture of adaptation of the common law, drawing on judgments regarding indigenous property rights in respect of former British possessions in Africa and India and in respect of indigenous claims in the United States and Canada, and reinterpretation of fact in the light of historical and anthropological research.

The doctrine of terra nullius, no one’s land, which has underlain the legal status of Aboriginal claims for years, has now been definitively disposed of. It was always insulting to the Aborigines that they should have been treated by the law as barbarians, with no kind of social organisation or sense of what we would call ownership of the land in which they lived.

The High Court has now accepted that ... the Aborigines were ... clearly in possession of their own structures of belief and social organisation, and a view of their relationship to the land.

The fact that this did not embrace individual private property is not relevant.

It is interesting to remember that the judgment serves to underline the essentially benign nature of British colonialism and territorial acquisition. The fundamental proposition according to the common law, as now interpreted following many precedents in other countries, is that where a territory is acquired by conquest or cession, the existing property rights in that territory under English common law remain in force.

The Australian Aborigines were unlucky enough not to have been treated by the English settlers as a conquered people but as people so primitive that they could not be considered to own land at all. Effectively what the High Court has now done is to restore to our Aborigines the dignified status of a conquered people, whose pre-existing rights ought to be respected.

FROM HAWKE TO HOWARD

- Reflections by history editor Alan Howe

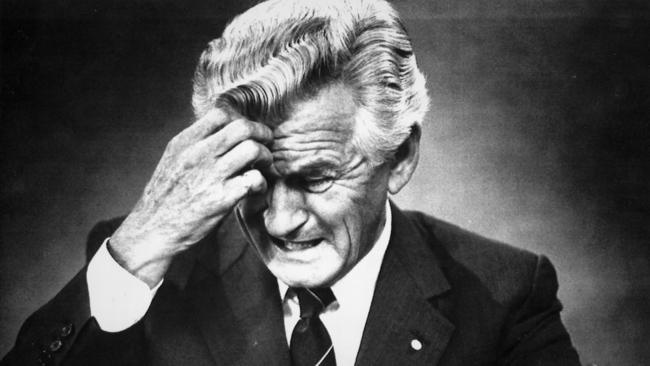

Bob Hawke won the March 1990 election, while shedding eight seats, his fourth victory – still a Labor record. But it was the final aria in the long opera of his prime ministership.

Few were aware of the Kirribilli House agreement struck between Hawke and his treasurer, Paul Keating, in June 1988, before trusted mutual friends businessman Sir Peter Abeles and ACTU secretary Bill Kelty. This deal agreed that should Hawke win the next election, he would make way early in the following term for Keating to succeed him. The proviso? Should the deal become public, it was off.

The two were arguably the most successful political partnership in the post-war era, but cracks in it were widening. Both men were ambitious and vain. The Rhodes scholar Hawke had successfully fashioned himself as a man of the people and he doubted that his smart but lightly educated offsider could do the same. Australia was sliding towards recession with jobless levels not seen since the 1930s. Hawke reneged on Kirribilli believing he alone could defeat the Liberals now headed by John Hewson, who, growing in popularity, threw down a robustly Thatcherite gauntlet: the 650-page Fightback! economic package that boldly included a goods and services tax.

An impatient Keating began undermining his leader. At an off-the-record gathering of journalists in Canberra – off the record is a fraught concept surrounded by competing reporters – Keating dismissed Labor legend John Curtin as “a trier”, said the country had never really had a strong leader and compared himself to Placido Domingo (the opera star’s long record of sexual harassment allegations was then unknown). The story soon leaked and Hawke’s camp called it “treachery”.

Keating was summoned to Hawke’s office for a four-hour meeting and reportedly pledged not to challenge for the leadership. But he did on June 3, 1991, and lost 66-44. The economy worsened, Hawke’s command loosened and Keating challenged again on December 19, winning 56-51.

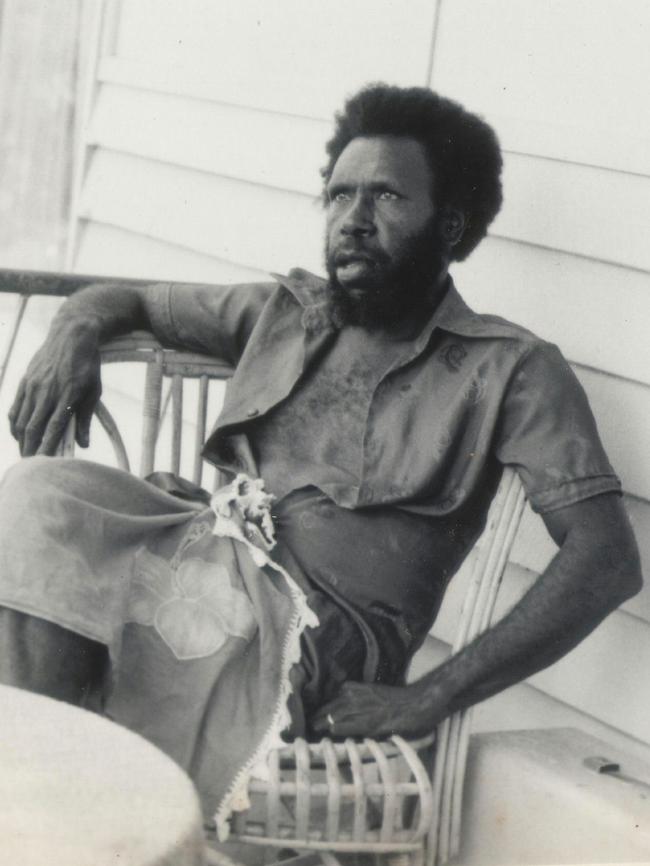

The following month, Eddie Mabo, who, as a gardener at James Cook University, had been shocked to learn his family did not own their ancestral land in the Torres Strait (it was deemed Crown Land), died aged 55. Nine years before he had started the first of a series of court actions culminating in Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) in the High Court. On June 3, 1992, the court dismissed the notion Australia had ever been terra nullius (owned by no one), recognising native title. Keating’s landmark Redfern speech that year set out his plan for a fairer Australia: “By doing away with the bizarre conceit that this continent had no owners prior to the settlement of Europeans, Mabo establishes a fundamental truth and lays the basis for justice … there is nothing to fear or to lose in the recognition of historical truth … there is everything to gain.”

The Berlin Wall had fallen, the Soviet Union was dissolving, and, briefly, the US was the sole superpower. In this role, it forged an unlikely 42-nation coalition – including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Qatar, Syria, Japan, Luxembourg and Australia – to evict Saddam Hussein after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. It took 42 days and cost 147 allied combat deaths but the job was done by February 28, 1992.

The most violent dividend of communism’s collapse erupted in Yugoslavia. Marshal Tito had ruled idiosyncratically since World War II, skilfully – sometimes through executions of pesky nationalists – keeping his six republics united. He died in 1980 and ethnic tensions increased as the Eastern bloc broke apart. The bitter conflicts lasted a decade and claimed 140,000 lives.

But while Europe was fragmenting, Englishman Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, making the globe at least a digital neighbourhood.

In 1990, Carmen Lawrence became Australia’s first female premier. Remarkable Australians shone in various fields: Peter Doherty won the Nobel prize in physiology; Adelaide’s Andy Thomas became our first astronaut; and Geoffrey Rush won the Best Actor Oscar for Shine. But perhaps the finest performer of the 1990s was John Howard, who, shunned by his party, described his chances of coming back as like “Lazarus with a triple bypass”. Keating saw off Hewson at 1993’s “unlosable election”, but Howard beat him in a 1996 landslide and stayed 11 years.

The decade had a last act to play out. On December 31, 1999, Russian president Boris Yeltsin resigned to be replaced by a little known former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin, who 15 years earlier had been working undercover in Auckland selling Bata shoes.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout