Xi diplomacy is secondary to defence strategy

The reality is just the reverse. This was made clear in the speech by Defence Minister Richard Marles to the annual Sydney Institute dinner on Monday night on the eve of the Albanese-XI meeting, with similar sentiments expressed by Foreign Minister Penny Wong in her Whitlam Oration last weekend.

Marles aspires to the most ambitious defence policy for Labor since Kim Beazley held the portfolio in the Hawke government. It is anchored in the conviction that Australia faces strategic challenges unprecedented in its history and driven by China’s aspirations to become the regional hegemon.

His warnings as Defence Minister could not be more explicit. Marles said the world is “more uncertain and more precarious than at any time since the end of the Second World War”. Mainly alluding to China, he said the Indo-Pacific was the site of the “biggest military build-up we have seen anywhere in the world over the past 70 years” with the risk that “this competition becomes confrontation”.

Marles builds upon but also shifts the dynamics in the defence policy of the Morrison government. His speech came with three main messages. First, in response to a more threatening environment, the new “cornerstone” of Australian strategic policy must be “impactful projection” which means holding potential adversaries at a distance through our ability to project military force.

This requires an Australian Defence Force that augments its self-reliance and can “deploy and deliver combat power” through greater strike capability. Australia must seek to defend its national interest by operations “within our immediate region”, the purpose being to “project power to shape outcomes and deter threats”.

This requires decisions that “strengthen the lethality, resilience and readiness of the ADF”. It means “hard choices” to reconfigure the ADF.

For Marles, a nuclear-powered submarine capability is “at the heart” of force projection. As Deputy Prime Minister, Marles is unwavering in his support for the AUKUS arrangement initiated by Scott Morrison with the UK and US. Marles not only supports the nuclear submarine capability but is re-fashioning strategic doctrine to locate the nuclear capacity within a framework of power projection. He said nuclear-powered submarines would give Australia “an unmatched strategic advantage” and “revolutionise the potency of the ADF”.

This entire narrative is driven by China. Senior ministers, of course, aren’t indiscreet enough to articulate the obvious. Marles renewed his pledge to announce in March – significantly, with the Prime Minister – the type of submarine and its optimal pathway. Critical in this decision is the arrival timetable and whether delivery can be brought forward.

Pivotal to this process is the Defence Strategic Review being conducted by Sir Angus Houston and former defence minister Stephen Smith that Marles previously said would be even “bigger” than the review by Paul Dibb for minister Beazley that transformed Australian defence policy in the 1980s.

Second, Marles has an activist view of the US alliance. He said the days “of simply paying the entry price to obtain our security guarantee” from America are finished. A more dangerous region renders the old thinking obsolete.

His foundational principle is that the US alliance, far from weakening Australia’s sovereignty as critics claim, actually “builds our sovereignty and reinforces our place in the region”.

This repudiates critics arguing that deeper military and technological ties with the US compromise our autonomy and sovereignty and undermine our standing with Asian neighbours.

“The Albanese government is completely committed to making Australia the most active participant in the alliance that we can be,” Marles said.

He said using the US to secure superior technology guaranteed Australia “more agency and sovereignty”, and that meant greater leverage within the region. Marles said he was pursuing deeper defence partnerships with Japan and India, his first two bilateral visits after taking office.

Australia’s purpose was not just to bolster its own security but work with regional structures to “contribute to an effective balance of military power” to ensure “no state will ever conclude that the benefits of conflict outweigh the risks”. Again, the undeclared yet obvious goal is balancing against China.

Third, Marles said that in a more dangerous world, Australia must make a greater defence effort, and it must have the will “to act on our own terms when we have to”. The defence budget would need to grow. This necessitated a new relationship between the Defence Department on one hand and Treasury and Finance on the other.

Marles criticised what he called the previous government’s paradigm of exempting defence from budget disciplines, saying it prioritised quantity over quality in the spend. The politics are obvious. Marles will face a moment of financial truth in the cabinet when ministers, facing competing demands, must decide between defence and social spending around health, aged care, and the NDIS. In making his case, Marles must be able to argue defence spending accountability, otherwise he has no hope.

The overall defence policy framework Marles outlines will incite progressive political hostility. As a realist, Marles would know his propositions about “impactful projection”, the US alliance and greater defence spending will attract dissent and fury in some quarters.

But Marles has one central advantage. It is the recognition among senior ministers, based on their security briefings, that China is embarked on a strategy of regional assertion with a willingness to use coercion. The case still mounted by critics who say China’s rise is relatively benign has no currency within the government’s higher reaches. That debate, in effect, is over.

The real debate is the reach and nature of Labor’s defence reconfiguration. Marles is aiming high and will need Albanese’s support to prevail. For Labor, this looms as an issue of destiny – it either embarks upon unprecedented defence decisions in response to China, or retreats before the security challenge as a government unfit for the task.

Last weekend, Wong said Labor would co-operate with China where it could and disagree where it must. But Wong invoked Gough Whitlam for her cause. She said the China of today is not the same as the China of the 1970s or even the 2000s and “it is an insult to all Gough did to prepare us for the future if we act as though we live in a world that has long since passed”. This is the authentic voice of Albanese Labor on China. No illusions.

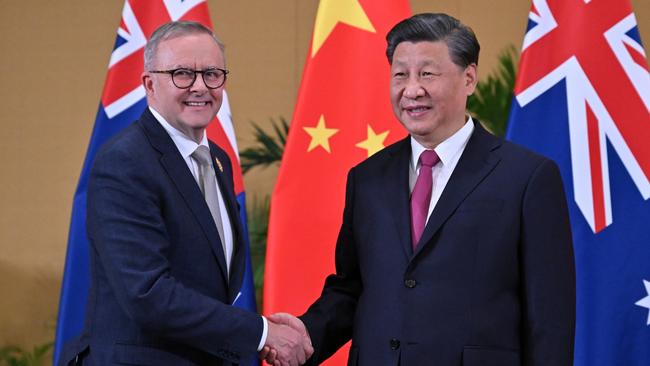

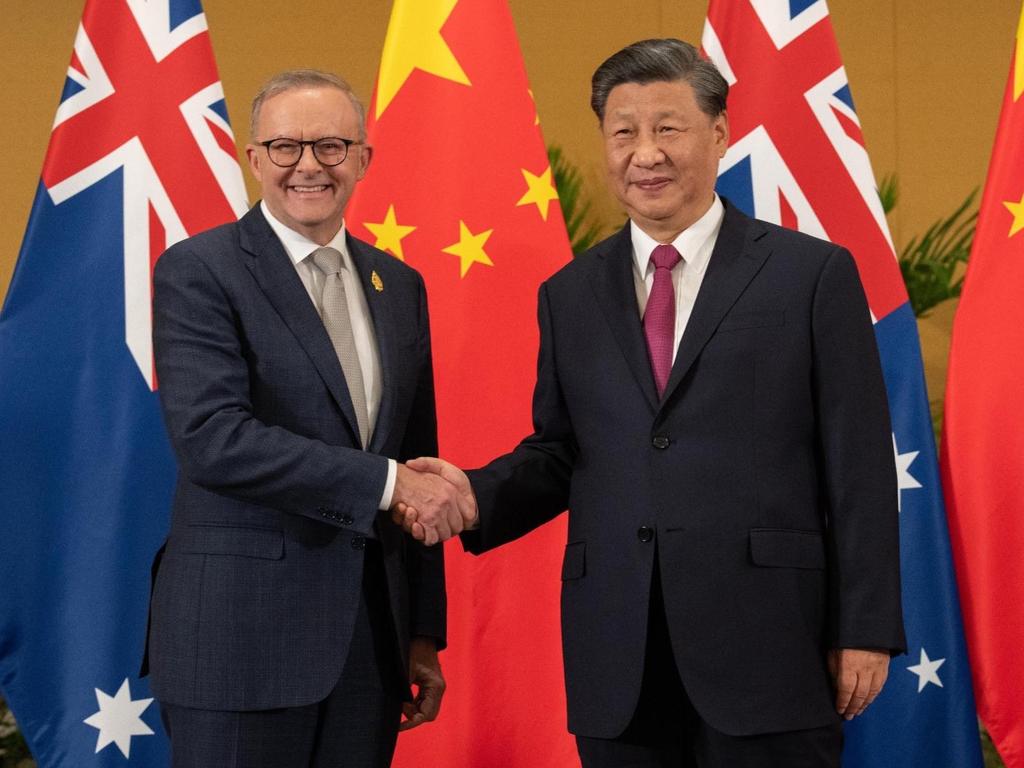

Albanese’s triumph is the restoration of dialogue. His related triumph, it seems, is dialogue without Australian concessions. He correctly says the meeting with Xi is a success because it happened.

Every sign is that Albanese is a hardnosed realist on China. That is imperative for Australia’s national interest and Labor’s electoral success.

Albanese seeks to normalise relations as far as possible yet, in reality, there are severe limits on any normalisation. Don’t get mesmerised by the diplomacy; check out the defence policy.

The Australia-China bilateral leaders’ meeting between Anthony Albanese and Xi Jinping is a diplomatic breakthrough for the new Labor government, ending the long freeze between the nations – but nobody should think this constitutes any strategic reset by Australia.