It has been that way for centuries, but the intervention of Pope Francis has renewed enthusiasm for social reform. The global town hall-style meetings he requested have produced bitter divisions on the politics of sex equality. While some reformist demands are reasonable, their rhetoric reveals a far broader agenda than equal opportunity for women. The so-called woke Pope is creating a more progressive church in his image but the growing politicisation of faith is unappealing.

The Catholic Church must change and women should lead the charge. It is the unspoken premise of demands made at the historic Plenary Council in Sydney last week. The panic set in after bishops rejected a motion (an amended version was later passed) concerning the greater recognition of women, including the ability to serve as deacons if the Pope approved the reform.

It was reported that the motion concerned equal opportunity, but its terms are far broader. It is couched in the language of identity politics including a demand for recognition that women’s opinions should be heard and valued simply because they are women.

The notion proved unacceptable to traditionalists, but it is equally insulting to anyone who believes in genuine equality.

There is nothing new about calls for women to enjoy greater equality of opportunity in the church. However, the horrors of priest pedophilia and the steady exodus of believers have left leaders wondering how to restore the faith and attract new members. In such a climate there will be those who believe more radical change is the only viable option and, if it fails, the organisation will fall.

The pro-reform camp seems unaware of the problems with its agenda. The Catholic Leader reported that dozens, mainly women, walked off in protest. They used emotionally charged language to describe the event, describing it as devastating and obliterating. Some started to cry. If you cannot handle the word no, or weep in the face of dissent, how can you expect an organisation to entrust you with a leadership role?

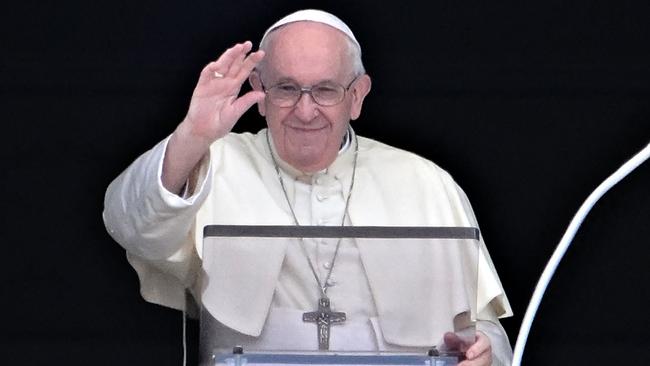

The decline in Catholic faith is part of a downward trend in religiosity across the West. Some church leaders believe greater recognition of women’s leadership skills will help to reverse the exodus. And the Pope is not waiting on plenaries to make change. Last week, he announced plans to appoint two women to the body responsible for selecting nominees for the role of bishop. Speaking to Reuters about his decision, Pope Francis said: “This way, things are opening up a bit.”

While the recognition of women’s intellectual heft and leadership skills in the church is celebrated as evidence of modernisation, the reality is probably more mundane. Western church leaders recognise that falling numbers of parishioners will continue to drive reforms to arrest decline. However, the future of the church is far from dim. According to the Vatican news agency, Fides, the number of Catholics grew by more than 15 million from 2018 to 2019. The increase applied to almost every continent except Europe, where the number decreased by almost 300,000.

In 2020, the Catholic population grew by 16 million to reach 1.36 billion worldwide. It is the largest denomination of Christianity, the world’s most popular religion. As reported by the Catholic News Agency, the pattern of growth in Africa and Asia remains while the percentage of Europeans observing Catholic faith continues to decrease.

For the persecuted faithful in Africa and Asia, the gender of priests and deacons is unlikely to present the most pressing test of their faith in God. For those who care little about gender politics, the most important quality of a preacher is the ability to move people with the word of God and lead the faith community to live good Christian lives. Yet it is unclear why the Catholic Church continues to defend the fallacy that half of humanity is unfit to lead the church because they were born female.

If they are concerned that more women in scholarly and priestly roles would diminish the reproduction of Catholic children, look at the emptying pews and decide how well the men-only policy is working. If they believe women are too emotional to provide stabile leadership, the emotionally charged scenes at the Sydney plenary would have done little to disprove the theory. If they reject greater representation of women in church leadership because it is framed in activist terms rather than derived from scripture, it is well justified. In theological debate, there is no higher authority than the word of God.

In a world of chaos, the Catholic Church can be reassuringly predictable. It guards scripture, keeps the faith, protects great art and architecture, defends the Vatican and rejects the popular doctrine of change for change’s sake. It is an extraordinary institution. Yet history may not be enough to withstand the rising tide of those who believe the future of Catholicism rests on greater recognition of women as equals to men in the church hierarchy.

Such is the panic about the decline of Catholicism that people wept when bishops affirmed the status quo of women in Sydney last week. The predictable stance of church leaders is that only men can ascend to the upper echelons of ecclesiastical power.