Why politicised universities are thwarting free debate on the Indigenous voice to parliament

But it was not surprising: at least 18 universities have issued similar statements. And, given the Stockholm syndrome that has gripped our elites, it was also unsurprising that the statements take cringe-worthiness to Olympic heights.

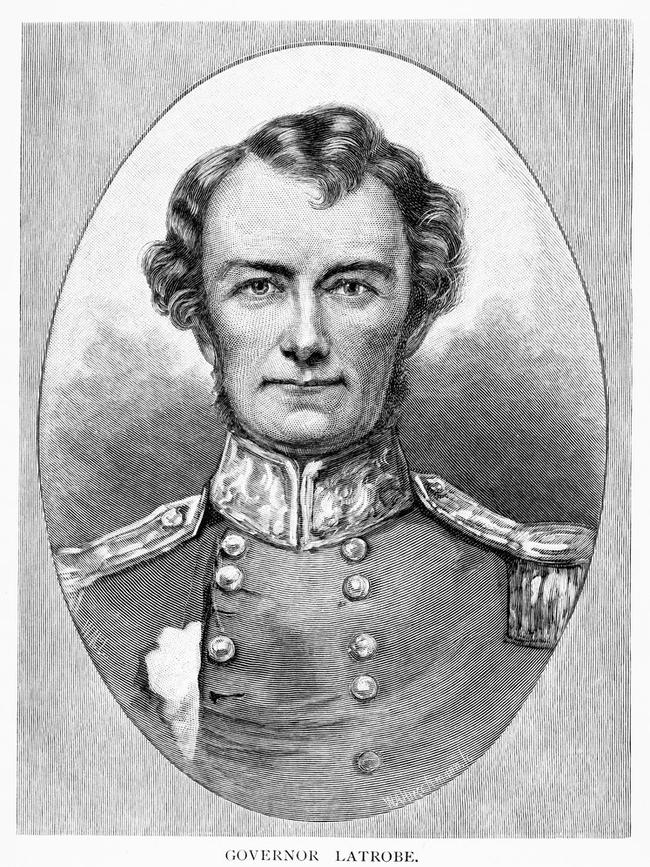

The chancellor and vice-chancellor of La Trobe, which is named after an eminent colonial governor, richly deserve that competition’s gold medal. Support for the voice, they declare, should be merely an element in a strategy of “decolonising” the university – leading one to wonder both whose colony it is and how it proposes to achieve self-determination.

Could it be, mirabile dictu, that La Trobe will secede from Australia and refuse public funding, thus sparing its tender souls the torments of self-loathing they endure every time the coloniser’s filthy lucre crosses their palm?

Au bloody contraire, as we French speakers say: decolonising is costly work, requiring dedicated centres, with their own highly paid professors, who can explain to the Very Bad Persons harbouring doubts about the voice why it is an Extremely Good Thing.

Nothing better exemplifies that genre than the document, mailed out with the ANU’s statement of support, that was produced by ANU’s First Nations Portfolio (yes, universities have such things). To discuss it is to experience the dilemmas a bee faces when it chances on a nudist colony: one doesn’t know where to start. Especially striking, however, in a document that purports to “address common concerns about the voice”, is the complete absence of balance or rigour.

We are told, for example, that “there is no scientific or biological foundation for the idea of race”.

Now, it is unquestionably true that “using genetics to rank populations demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of genetics”, as is asserted by the sole source the document cites. But anyone familiar with modern systematics (the theory of biological classification) knows human groups that have developed largely independently over extremely long periods can and in some cases clearly do form distinct races; that is, broadly monophyletic populations whose members share significant characteristics, ranging from distinctive physiognomy to differential disease vulnerability.

That those variations cannot justify racial discrimination hardly needs saying. But it should also not need saying that if the ANU wants to comment on these issues, it ought to do so accurately. The document it mailed out does not. Yet that sin of omission is merely a prelude to sins of commission. Thus, assume, putting the science aside, that the document is correct in claiming “race is a social construct”; to deduce from that proposition the inference that “there is no such thing as ‘race’ ” is absurd.

The reality, as Alfred Schutz, the pioneer of social constructivism, brilliantly explained in the 1950s, is precisely the opposite: the distinguishing feature of social constructions is their “facticity”, the way they shape the “lifeworld” of everyday existence.

A simple example makes the point: money is a social construct, underpinned by a complex of social and institutional conventions. But a person who claimed a $50 bill was only a fancily decorated piece of plastic would be regarded as deeply confused. And if that person proclaimed “there is no such thing as money”, they would be promptly dispatched to the local home for the bewildered.

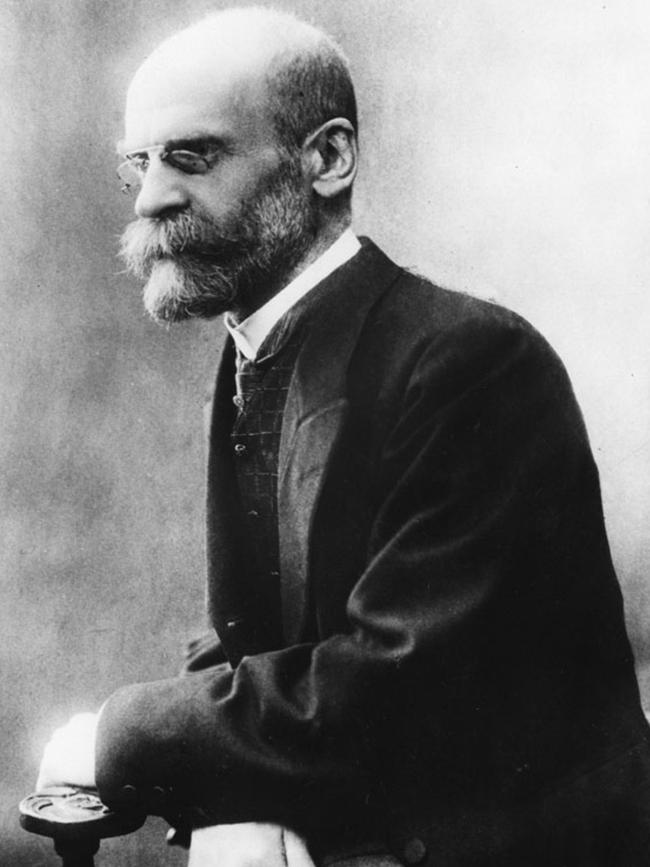

That is why the great sociologist Emile Durkheim argued – in The Rules of Sociological Method (1895) – that “treating social facts as facts” is the very first rule of serious social analysis.

In flouting that rule, the ANU is not just displaying its superficiality; it is eliding a crucial aspect of the current debate. There is, more specifically, no escaping this country’s history of racial differentiation – a differentiation that may have been socially constructed but has been all too real. The crucial question is whether establishing an assembly such as the voice will help us overcome that history’s legacy or will entrench it.

That question is scarcely virgin soil in terms of scholarly research. First raised by Thomas Hobbes, and then pursued by a line of scholars that stretches from John Stuart Mill and Hannah Arendt to today’s social constructivists, the relevant reasoning is pretty clear: create a distinct system of representation for group A, from which other citizens are excluded, and the likely effect will be to sharpen social cleavages, by heightening pre-existing perceptions and resentments both in group A and in the rest of the population.

Moreover, the greater the extent to which group A will capture the benefits, but not shoulder the costs, of any outlandish demands, the harsher and more destructive will be the conflicts that separate representation creates.

The experience of Indigenous assemblies here and overseas bears those insights out; but the ANU document ignores them altogether. That error, and myriad others, must have been obvious to many of the university’s academics. Why then weren’t the university leadership’s dubious assertions challenged? How is it that no one insisted on the other side being considered, and its arguments fairly put?

Perhaps the academics weren’t consulted. It is, however, reasonable to ask whether they would have objected to the inaccuracies if they had. Wouldn’t setting oneself against the First Nations Portfolio be to join the camp of blackest reaction, and to be done for, morally cashiered, banished from the land of the enlightened and virtuous? Wouldn’t it be more prudent to unctuously do what the unicrats regard as “the right thing” – even if the right thing isn’t the correct thing?

That is precisely what Alexis de Tocqueville meant by the “tyranny of the majority”: the fear of being excommunicated that, over time, allows public judgment to infiltrate individual consciousness, changing our perceptions of the world and sapping – before it eliminates – the courage to chart one’s own course.

Bad enough doing that to teachers; even worse inflicting it on students, who are robbed of the most valuable benefit a university can offer: the experience of learning in an environment in which people think for themselves.

Ultimately, however, the greatest damage will be to the universities. By stampeding to toe the party line on an issue that is quintessentially political, rather than acting as a forum where serious views contend, our rabble of academic lemmings merely prove how intensely politicised Australia’s universities have become.

They could have left to Caesar – the political system – what is of Caesar: the task of weighing up conflicting values and perspectives. Instead, by intruding on Caesar’s turf, they have extended an open invitation for Caesar to intrude on theirs. Let them remember that when Caesar, armed and angry, comes marching in.

It was disappointing to receive a message from the chancellor and vice-chancellor of the Australian National University, and then from the university council, formally endorsing the Indigenous voice to parliament.