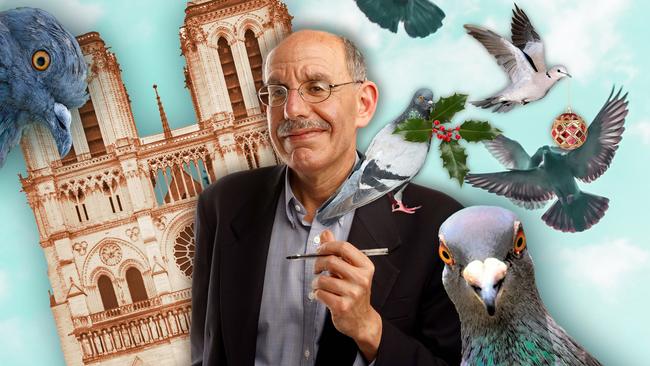

Opened in 1860, housed beneath the cast iron awnings that are Paris’s pride and joy, Covid finally killed it off. It had long teetered on the brink, losing first one seller and then another. But for the city’s pigeon fanciers, the bird market, nestled behind the cathedral, eclipsed even that most dazzling of architectural wonders.

Brimming with portly Mondaines, magnificently plumed Jacobins (which, despite their name, were Queen Victoria’s favourite breed) and sleek Voyageurs that could soar from zero to 60km/h in seconds, there was no better place to while away a quiet hour, particularly on wintry days when nature’s beauty vanishes beneath the gloom.

There, gathered around the finest specimens, were animated clutches of admirers, arguing passionately about the birds’ relative merits. And there too were penniless students, dreaming of hosting a mating pair on the windowsill of garrets that would, decades later, fall victim to Airbnb’s inexorable advance.

The place seemed timeless. But when the market’s predecessor opened, it was literally revolutionary. Beginning in the late Middle Ages, ever greater restrictions had been placed on the right to own, breed or hunt pigeons. As the centralised state tightened its grip, the nobility’s ancient privileges were formalised, culminating in 1699 in laws that limited the ownership of pigeons and other fancy birds to the aristocracy’s highest ranks.

To make things worse, tenants were not allowed to prevent a lord’s pigeons from consuming their crops, with fearsome punishments for transgressors. Given that a thousand pairs of pigeons could consume 200 tons of grain per year, few restrictions caused more unrest in the hungry years that preceded the French Revolution.

Nor was France unusual: similar restrictions prevailed throughout the German principalities and in England. Little wonder then that fancy birds featured so prominently in The Twelve Days of Christmas: no gift could have been more prized, nor more out of reach. And little wonder too that when the Revolution, on August 4, 1789, swept the restrictions away, all of Europe shook.

Suddenly, the pigeon was thrust into mainstream of everyday life. By 1815, modern pigeon racing had taken shape; breeding clubs, and societies of pigeon fanciers, quickly followed.

This was an activity as egalitarian as it was popular: the 19th century, with its mania for rules, developed intricate pedigree systems for horses and dogs, but pigeons were always judged on their calibre, not their ancestry. Easily within the reach of the respectable working class, readily accommodated in cramped backyards, pigeon coops brought nature’s touch to burgeoning metropolises.

Nor was it just a working-class pastime. Charles Darwin, to take but one example, was a keen pigeon fancier, who relished relaxing in the pubs to which London’s fanciers repaired after a day’s racing. And when his publisher sent the Origin of Species to a referee, the referee suggested that Mr Darwin should simply have written a guide to pigeon breeding, for while the Origin was likely to gather dust on booksellers’ shelves, “every body is interested in pigeons”.

“Every body” included Australia. By the 1880s, pigeon racing was integral to colonial life. It is no accident that in Frank Hardy’s Power Without Glory, John West starts his life of crime by fixing a pigeon race: a man who could do that was capable of anything.

But trouble was brewing. Just as the pigeon was becoming the working man’s best friend, 19th century Romanticism, with its nostalgia for nobility and the medieval world, glorified a biologically groundless distinction between the pigeon, whose ordinariness the Romantic poets despised, and the alleged purity of the dove.

Did it matter that while racing pigeons can distinguish the letters of the alphabet, Hosea 7:11 tells us that doves are “silly and without sense”? Or that the ancients praised pigeons’ marital fidelity while casting the dove as the symbol of shamelessly promiscuous Venus? And what about the fact that no military couriers ever proved braver than pigeons, winning more Dickin Medals (the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross) than any other animal species?

None of that made any difference – and worse was to come. Not only was the unassuming pigeon overshadowed by that ostentatious parvenu, the dove; it was reduced to a pariah.

The assault opened on June 22, 1966, when Thomas P. Hoving, New York’s parks commissioner, lambasted the city’s pigeons as “rats with wings”. Echoed in Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories, the phrase became a rallying cry for town planners worldwide.

It is unsurprising that the assault on what were now seen as urban anarchists, living where they wanted and flying as they pleased, was led by socialists, the ultimate busybodies. In the USSR, Moscow’s leading planner announced that “millions of these cooing birds are to be banished from the metropolis, sucked up by gigantic vacuum cleaners and resettled in Siberia”.

Ken Livingstone, the socialist mayor of London, followed suit, declaring a jihad on the pigeons of Trafalgar Square. Never to be outdone, Dan Andrews’s Victoria allowed or even encouraged councils to adopt methods of pigeon control it would scarcely contemplate for rabid dogs, let alone doves.

Everywhere, the pigeon – the animal that, as the towering 18th century naturalist, George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, put it, shows that “the greatest faithfulness can be combined with the greatest love of freedom” – is on the run. The now decade-long stagnation, in our price index, of the price of turtledoves (which are just pigeons) highlights the entrenched malaise.

No, the clock won’t be turned back. The old bird market’s days are over. Pigeon fancying, once the gentle pursuit of millions, may go the way of stamp collecting, which shares so many of its qualities. The petty tyrants’ assault won’t abate.

But the humble pigeon will not be so easily defeated. A loving individualist, it has learned, throughout the centuries, to specialise in escape, eluding attackers, tenderly nourishing its carefully hidden children, always finding the way home.

This year, when Christmas, which celebrates new life, and Hannukah, with its message of courage and endurance, overlap, that is the spirit we need to toast. Thank you, dear readers, for accompanying my column on its flight through 2024. And may that spirit transport you, soaring on the surest of wings, into a year of health, happiness and, above all, peace.

This Christmas, seeing Notre Dame, risen from the ashes, will be a special treat for millions around the world. But while marvelling at its reconstruction, it is hard not to mourn the disappearance of its modest, now largely forgotten, neighbour.